The presenter of the Annual Lecture of the Scottish Society for the History of Photography (SSHoP) at the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh on 15th November 2019, was the contemporary fine art photographer Garry Fabian Miller. His presentation lasted just over one hour in which he described his career to date in detail including his family background, influences, a brief description of his early social documentary and landscape work, the thinking behind his switch in 1984 to camera-less photography, his current working practice and his collaborations with other artists, writers, poets and musicians.Born in 1957 to parents who ran (and lived in) a long established family studio photography business in Bristol, he was immersed in the atmosphere of the darkroom from early childhood. As a teenager his ambition was to become a 'serious' photographer, at a time when this effectively equated with social documentary photography. His first significant project as a teenager, influenced by the work of Paul Strand in the Outer Hebrides, involved at the age of sixteen, spending the summer of 1973 in the Shetland Islands, living with and documenting the lives of crofters and their families. Several of these images featured in the lecture and this experience of the cycles of rural life in remote wild places, has been a major influence on his life and work since then.A singular feature of his practice has been his use of Cibachrome paper and the dedicated chemistry required to process it, to produce all of his images since 1976. This dye destruction paper, designed as a reversal process for producing direct positive prints from colour transparencies, was known for its distinctively vivid but true to life colour palette, strikingly high gloss almost metallic surface finish and exceptional archival stability. Fabian Miller found that with long enough exposures, he was able to use this paper instead of film in a 10x8 inch large format camera, to photograph seascapes of the Severn Estuary from an attic window in his home. This resulted in 'Sections of England: The Sea Horizon' his first major work, which was first shown in 1977 in the Serpentine Gallery in London and formed the basis of his first solo exhibition in the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol in 1979.He moved to live in a farm in Lincolnshire in 1980 and having developed an interest in Land Art, he transformed a barn into a small gallery, where he met and showed the work of among others Hamish Fulton, Andy Goldsworthy, David Nash, Marie Yates and Roger Ackling. In 1984 he started experimenting with the use of semi-translucent natural materials, grasses, leaves, seed heads and flower petals, placed in the negative carrier of his enlarger and exposed onto Cibachrome paper to make photographs direct from life. By the following year he had decided at the age of 25, that he no longer needed a camera. He made several seasonally based series of images, documenting the sequential changes in the colour of leaves as the chlorophyl levels changed over a period of weeks and several of these are now in the permanent collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.In 1989 he moved with his family to Dartmoor, designed and built a studio with his darkroom at the bottom of their large garden, where he estimates he has spent at least fifty per cent of his waking hours ever since. In around 1992 he virtually stopped using plant materials having developed a technique for projecting beams of light, filtered through glass vessels containing coloured oils and liquids, directly onto photosensitive paper, with only small pieces of card placed in the light path to produce the geometric shapes in his photographs. His work has become progressively more abstract and since 2017, he has experimented with using additional small light sources, for example burning matches, to produce localised bright highlights mimicking the appearance of flames. His daily routine also involves walking , either in the early morning or the evening, taking inspiration in the special auras of light in the skies and the colours this produces in the blossoms of the vegetation, along with the atmosphere of the ancient archeological sites and burial cairns on the surrounding moorland, which he tries to represent in his work. Although most of his work has been made in his own darkroom, he has made some images on visits to the islands of Tiree, off the West coast of Scotland, Skellig Michael and Inis Meain (one of the Aran Islands), both off the West coast of Ireland. He described Inis Meain as one of the last bastions of purity in Ireland, a view shared by the artist Sean Scully, who made one of his few books of photographs on the island. While Fabian Miller always works alone in his darkroom, when it comes to distributing his work he has collaborated extensively with other artists including writers, poets, musicians, potters, weavers and curators. One of his most important collaborations over the years has been with Martin Barnes, the curator of Photography at the V&A Museum, who has aquired his work for their collection, wrote an introduction to one of his books, curated his 2005 exhibition at the V&A and included his work in the major retrospective exhibition of camera-less photography, 'Shadow Catchers' also at the V&A in 2011. Several other authors have also contributed to sections in his books, including Marina Warner, Nigel Warburton and Adam Nicolson (The Colour of Time, 2010) and the author and ceramicist Edmund de Waal with the poet Alice Oswald (Blaze, 2019). Alice Oswald has also collaborated in live performances of his work along with her poetry as has the cellist and composer Oliver Coates. Since 2013, Fabian Miller has also worked with the weavers in the Dovecot Studio in Edinburgh, making gun tufted rugs (some of which have been acquired by the Standard Life Aberdeen Investment Bank for the foyer of their Edinburgh Head Office - see photograph above) and in 2017 a tapestry, based on the colours and shapes in his photographs. Probably his most important collaboration over the last ten years has been with John Bodkin a master of digital printing who has helped in the challenging process of colour correcting high resolution scans of Fabian Miller's Cibachrome prints, while trying to maintain as closely as possible the subtleties of their original appearance and surface. This allows them to be re-printed to archival standards as 'C'prints using the Lambda Lightjet printing system, for exhibition at a much larger scale. Some of these prints were recently exhibited at the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh who have also worked closely with Fabian Miller for many years (see previous post from 16 Dec 2019).Moving into the third decade of the 21st century, it is relatively unusual to find an internationally acclaimed photographer whose primary method of creating images is so completely dependent on a traditional wet darkroom process. This is all the more surprising on discovering that no Cibachrome papers have been manufactured since 2012. Cibachrome papers are relatively stable if correctly stored (in a freezer) and Fabian Miller had the foresight to stock up when the last batch was produced. This supply is running out and he is down to his last one hundred sheets. There may be a few individuals around the world who still have small stocks in storage but they are unlikely to become available and their archival status will be unpredictable. The Cibachrome process chemistry is if anything more difficult to store and although there are possible work arounds using monochrome developers and RA4 process bleach/fix, he has decided that when he completes his current project using his remaining stock, he will close his darkroom forever. A very well written account of the saga of the demise of Cibachrome/Ilfochrome is available online (Vincent 2018).Under the circumstances, Fabian Miller seems remarkably optimistic about the future. He has a large library of work already made and now has access to the skills required to work with this digitally. He stopped selling his Cibachrome originals some time ago to retain them for future projects and now only sells his work as Lambda Lightjet 'C'prints. Although his work has can appear very precise and controlled, his almost poetic relationship with the elemental forces which shape his connection to the land are still very apparent. He discovered very recently that the building in Bristol in which he had been brought up, was at one time owned by the publisher Joseph Cottle. In one of their well documented walking tours in the 1790's, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, stayed for several days with Cottle in Bristol, before crossing the Severn by ferry to travel up the Wye Valley to Tintern. It transpires that Dorothy Wordsworth slept in the bedroom, which in later years became the darkrooom in which he still remembers playing as a child, while his parents were printing their work. He is currently trying to work out if there is a way of using this in the generation of his next project.The importance of the darkroom and its role in the history of the photography which so dramatically transformed our interactions with the rest of the world, can perhaps only be fully appreciated by those who have experienced working in one. In an attempt to address this, Historic England spent several days with Fabian Miller in 2016, documenting his working process. He has also made arrangements with the V&A Museum that when he does close his darkroom, it will be dismantled and installed in their Photography section as a new exhibit for visitors to experience. His archive of darkroom notebooks will also be acquired by the museum to be made available to future researchers.In discussion following the lecture, he was asked if his experience of the demise of Cibachrome felt like coming to the end of a prolonged terminal illness. While agreeing that the end of Cibachrome was sad, he feels that the potential of digital photography is exciting and that it is probably still in its infancy, with much still to be explored. He feels that it is important that people understand that the invention of chemical photography was a seminal moment in world history and is encouraged by the fact that there are still people who are trying to keep it alive. He has been thinking for some time about the early experiments of Fox Talbot and his correspondence with John Herschel, wondering if there is any scope for further research into this source material for clues as to developing other new processes. Examples of Fabian Miller's work and links to interviews with him are available at the websites of the V&A Museum, the Ingleby Gallery and on his own site, at www.garryfabianmiller.com. Barnes M. and Fabian Miller G. (2005) 'Illumine'. Merell Publishing London.Barnes M. (2012) 'Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography'. Merell Publishing London.Fabian Miller G. (2010) 'The Colour of Time'. Black Dog Publishing, London.Fabian Miller G. (2019) 'Blaze" Ingleby, Edinburgh.Scully S (2007) 'The Walls of Aran' Thames and Hudson, London.https://www.inglebygallery.com/artists/51-garry-fabian-miller/overview/https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/garry-fabian-miller

Since 2013, Fabian Miller has also worked with the weavers in the Dovecot Studio in Edinburgh, making gun tufted rugs (some of which have been acquired by the Standard Life Aberdeen Investment Bank for the foyer of their Edinburgh Head Office - see photograph above) and in 2017 a tapestry, based on the colours and shapes in his photographs. Probably his most important collaboration over the last ten years has been with John Bodkin a master of digital printing who has helped in the challenging process of colour correcting high resolution scans of Fabian Miller's Cibachrome prints, while trying to maintain as closely as possible the subtleties of their original appearance and surface. This allows them to be re-printed to archival standards as 'C'prints using the Lambda Lightjet printing system, for exhibition at a much larger scale. Some of these prints were recently exhibited at the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh who have also worked closely with Fabian Miller for many years (see previous post from 16 Dec 2019).Moving into the third decade of the 21st century, it is relatively unusual to find an internationally acclaimed photographer whose primary method of creating images is so completely dependent on a traditional wet darkroom process. This is all the more surprising on discovering that no Cibachrome papers have been manufactured since 2012. Cibachrome papers are relatively stable if correctly stored (in a freezer) and Fabian Miller had the foresight to stock up when the last batch was produced. This supply is running out and he is down to his last one hundred sheets. There may be a few individuals around the world who still have small stocks in storage but they are unlikely to become available and their archival status will be unpredictable. The Cibachrome process chemistry is if anything more difficult to store and although there are possible work arounds using monochrome developers and RA4 process bleach/fix, he has decided that when he completes his current project using his remaining stock, he will close his darkroom forever. A very well written account of the saga of the demise of Cibachrome/Ilfochrome is available online (Vincent 2018).Under the circumstances, Fabian Miller seems remarkably optimistic about the future. He has a large library of work already made and now has access to the skills required to work with this digitally. He stopped selling his Cibachrome originals some time ago to retain them for future projects and now only sells his work as Lambda Lightjet 'C'prints. Although his work has can appear very precise and controlled, his almost poetic relationship with the elemental forces which shape his connection to the land are still very apparent. He discovered very recently that the building in Bristol in which he had been brought up, was at one time owned by the publisher Joseph Cottle. In one of their well documented walking tours in the 1790's, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, stayed for several days with Cottle in Bristol, before crossing the Severn by ferry to travel up the Wye Valley to Tintern. It transpires that Dorothy Wordsworth slept in the bedroom, which in later years became the darkrooom in which he still remembers playing as a child, while his parents were printing their work. He is currently trying to work out if there is a way of using this in the generation of his next project.The importance of the darkroom and its role in the history of the photography which so dramatically transformed our interactions with the rest of the world, can perhaps only be fully appreciated by those who have experienced working in one. In an attempt to address this, Historic England spent several days with Fabian Miller in 2016, documenting his working process. He has also made arrangements with the V&A Museum that when he does close his darkroom, it will be dismantled and installed in their Photography section as a new exhibit for visitors to experience. His archive of darkroom notebooks will also be acquired by the museum to be made available to future researchers.In discussion following the lecture, he was asked if his experience of the demise of Cibachrome felt like coming to the end of a prolonged terminal illness. While agreeing that the end of Cibachrome was sad, he feels that the potential of digital photography is exciting and that it is probably still in its infancy, with much still to be explored. He feels that it is important that people understand that the invention of chemical photography was a seminal moment in world history and is encouraged by the fact that there are still people who are trying to keep it alive. He has been thinking for some time about the early experiments of Fox Talbot and his correspondence with John Herschel, wondering if there is any scope for further research into this source material for clues as to developing other new processes. Examples of Fabian Miller's work and links to interviews with him are available at the websites of the V&A Museum, the Ingleby Gallery and on his own site, at www.garryfabianmiller.com. Barnes M. and Fabian Miller G. (2005) 'Illumine'. Merell Publishing London.Barnes M. (2012) 'Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography'. Merell Publishing London.Fabian Miller G. (2010) 'The Colour of Time'. Black Dog Publishing, London.Fabian Miller G. (2019) 'Blaze" Ingleby, Edinburgh.Scully S (2007) 'The Walls of Aran' Thames and Hudson, London.https://www.inglebygallery.com/artists/51-garry-fabian-miller/overview/https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/garry-fabian-miller

Vincent D (2018) A Brief History of Cibachrome Online at: https://douglasvincent.com/ilfochrome/history.html Accessed 11 February 2020

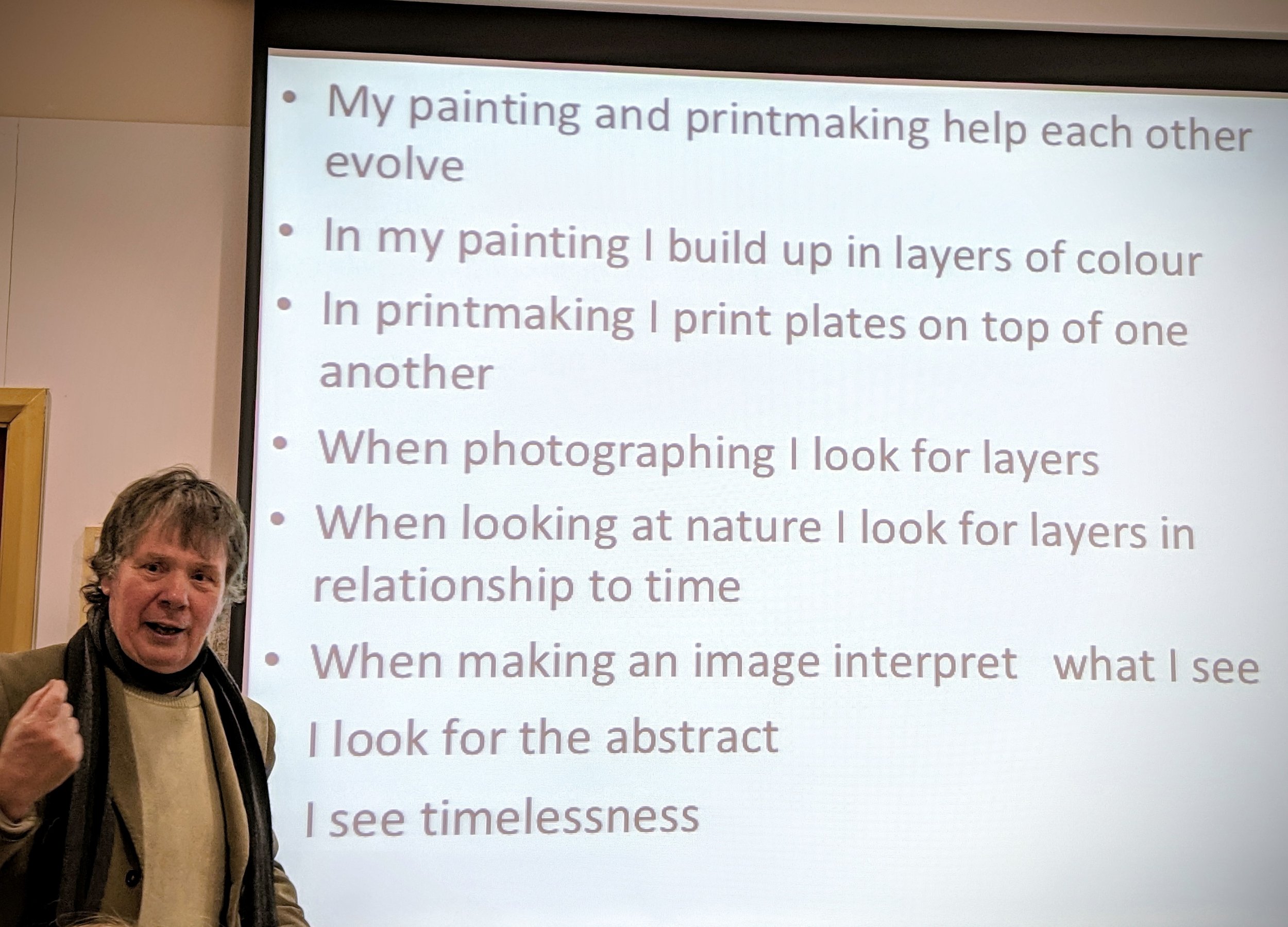

He explained that until recently, he had been wary of using photography as he felt this was almost like cheating. When he started using a digital SLR camera he discovered that the learning process was more complicated than he had anticipated; the main difficulty being obtaining a perfect tonal range which would be compatible with his printmaking processes. After a fair amount of "learning by mistakes" he has found that photography and image processing (layering in Photoshop) is now influencing his painting which has become "more abstract, in a round about way". He feels the main difference between most photographers and painters is that photographers feel they need to know what the end result will be at the time they press the shutter - i.e. classic 'pre-visualisation' as advocated by Ansel Adams (Schaefer, 1992) and the f64 group (and most photographers since then). In his printmaking, especially with multiple layers of coloured inks, he seldom knows what it will look like when finished and part of the process of abstraction is that the image evolves layer by layer, as it is being made.

He explained that until recently, he had been wary of using photography as he felt this was almost like cheating. When he started using a digital SLR camera he discovered that the learning process was more complicated than he had anticipated; the main difficulty being obtaining a perfect tonal range which would be compatible with his printmaking processes. After a fair amount of "learning by mistakes" he has found that photography and image processing (layering in Photoshop) is now influencing his painting which has become "more abstract, in a round about way". He feels the main difference between most photographers and painters is that photographers feel they need to know what the end result will be at the time they press the shutter - i.e. classic 'pre-visualisation' as advocated by Ansel Adams (Schaefer, 1992) and the f64 group (and most photographers since then). In his printmaking, especially with multiple layers of coloured inks, he seldom knows what it will look like when finished and part of the process of abstraction is that the image evolves layer by layer, as it is being made. Expanding on this, he explained that in deciding what to photograph he looks for the the most obscure and abstract things he can find, often now looking in nature for visual representations of layers; one tree in front of others, shadows on rocks or sand, layers in dead wood or rock formations, layers in time. In interpreting what he can see, he is taking from nature then playing and abstracting from it. He described this process as "being like building with Lego - start with the finished object - take it apart then re-build it - it will look similar but not exactly the same".To my surprise, I found that I had more in common with his approach than I had expected. In discussion with the audience, he talked of shadows in art as having ambiguity, transience - similar to the feelings I have been trying to capture in my photographs of shadows. I had not previously grasped the significance of layers but in many of my images, that could be what gives them the impression of texture. I felt comfortable with his explanations of abstraction, a concept I have had difficulty fully understanding previously. He is clearly happy now using a hybrid of digital photography and traditional printing, feeding contemporary technology into long established analogue processes. He is going to be in Greece for the next couple of months but has offered to let some of us visit his studio to share his technical knowledge. Having never seen photo-etching in practice or intaglio prints being made, I still have some difficulty in understanding exactly how it works and this is now on my list to do over the summer. I am sure that the learning curve for developing his printmaking skills was much steeper and longer than it took him to get what he needed from digital photography but I am still interested in printing digital negatives on acetate for use with historical U-V light based photographic processes and his advice on file preparation and printing technique could be invaluable.His final comment on his acceptance of photography as a tool for image making was to concede that "the mobile phone has become the sketch-book of the 21st century".The images used to illustrate this post were captured on my mobile phone camera.Schaefer JP (1999) 'Visualisation: The Art of Seeing a Photograph' In: Ansel Adams Guide - Basic Techniques of Photography Book (1); Revised edition, Boston-New York-London, Little, Brown and Company, pp 131-134.

Expanding on this, he explained that in deciding what to photograph he looks for the the most obscure and abstract things he can find, often now looking in nature for visual representations of layers; one tree in front of others, shadows on rocks or sand, layers in dead wood or rock formations, layers in time. In interpreting what he can see, he is taking from nature then playing and abstracting from it. He described this process as "being like building with Lego - start with the finished object - take it apart then re-build it - it will look similar but not exactly the same".To my surprise, I found that I had more in common with his approach than I had expected. In discussion with the audience, he talked of shadows in art as having ambiguity, transience - similar to the feelings I have been trying to capture in my photographs of shadows. I had not previously grasped the significance of layers but in many of my images, that could be what gives them the impression of texture. I felt comfortable with his explanations of abstraction, a concept I have had difficulty fully understanding previously. He is clearly happy now using a hybrid of digital photography and traditional printing, feeding contemporary technology into long established analogue processes. He is going to be in Greece for the next couple of months but has offered to let some of us visit his studio to share his technical knowledge. Having never seen photo-etching in practice or intaglio prints being made, I still have some difficulty in understanding exactly how it works and this is now on my list to do over the summer. I am sure that the learning curve for developing his printmaking skills was much steeper and longer than it took him to get what he needed from digital photography but I am still interested in printing digital negatives on acetate for use with historical U-V light based photographic processes and his advice on file preparation and printing technique could be invaluable.His final comment on his acceptance of photography as a tool for image making was to concede that "the mobile phone has become the sketch-book of the 21st century".The images used to illustrate this post were captured on my mobile phone camera.Schaefer JP (1999) 'Visualisation: The Art of Seeing a Photograph' In: Ansel Adams Guide - Basic Techniques of Photography Book (1); Revised edition, Boston-New York-London, Little, Brown and Company, pp 131-134.

The rock formations photographed for this article are near the Western end of Porth Ceiriad on the Lleyn Peninsula. The colours in life are subtle and muted and I have 'enhanced' them to a point where they are no longer true representations of what I saw but the photographs are now a better representation of their perceived effect when I was there. I doubt if I would previously have treated them in this way but the result feels acceptable, perhaps because the interaction of the almost complementary orange browns and bluish greys remains harmonious. Nobody unless they were there at that time could know the difference but have I sacrificed photographic integrity for a more pleasing aesthetic effect?Albers J (1963). 'Interaction of Color'. New Haven, Yale University Press. p1 (My edition of this is the Fiftieth Anniversary (4th) Edition of the paperback version, still in print and published in 2013).

The rock formations photographed for this article are near the Western end of Porth Ceiriad on the Lleyn Peninsula. The colours in life are subtle and muted and I have 'enhanced' them to a point where they are no longer true representations of what I saw but the photographs are now a better representation of their perceived effect when I was there. I doubt if I would previously have treated them in this way but the result feels acceptable, perhaps because the interaction of the almost complementary orange browns and bluish greys remains harmonious. Nobody unless they were there at that time could know the difference but have I sacrificed photographic integrity for a more pleasing aesthetic effect?Albers J (1963). 'Interaction of Color'. New Haven, Yale University Press. p1 (My edition of this is the Fiftieth Anniversary (4th) Edition of the paperback version, still in print and published in 2013).

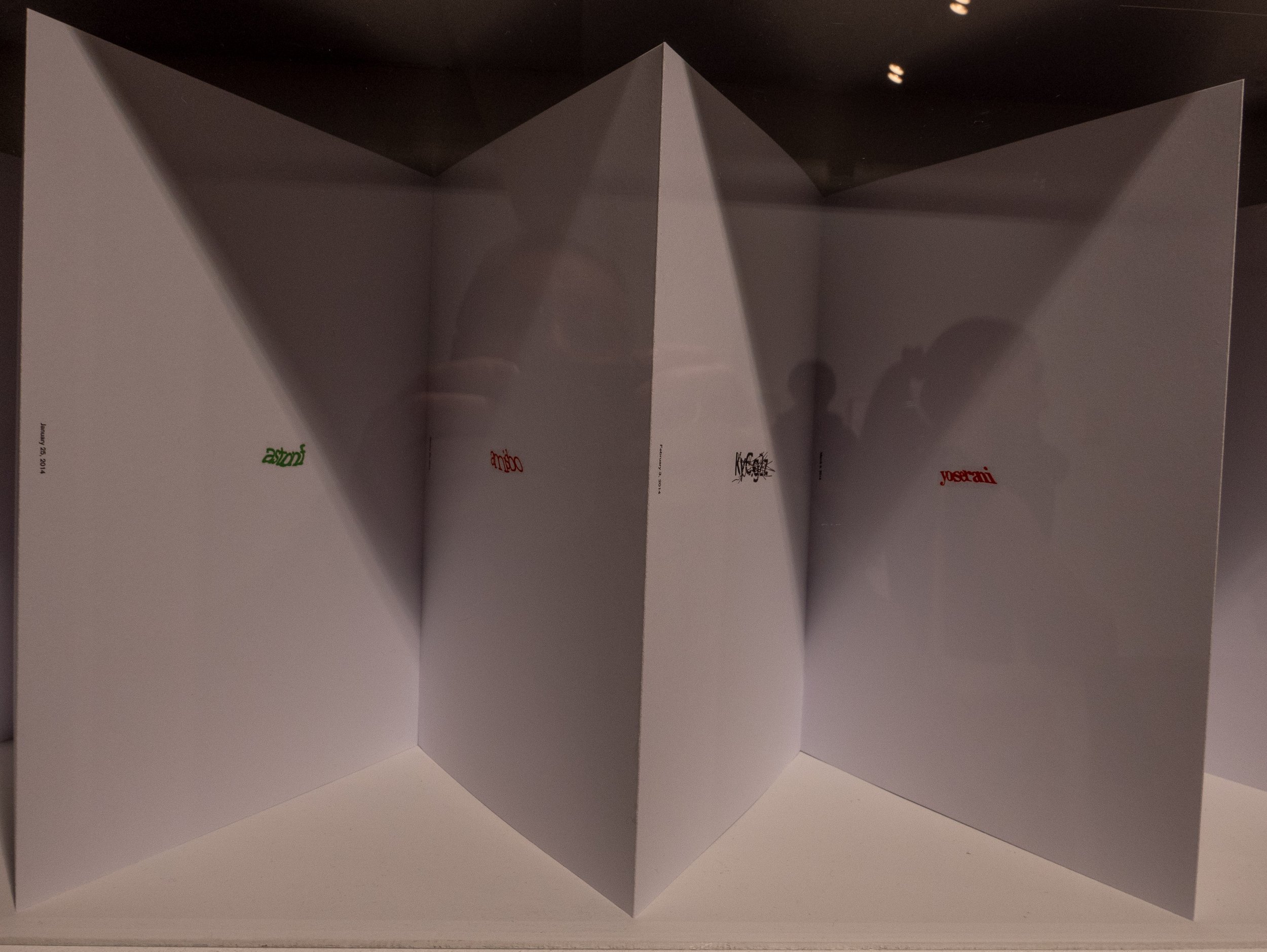

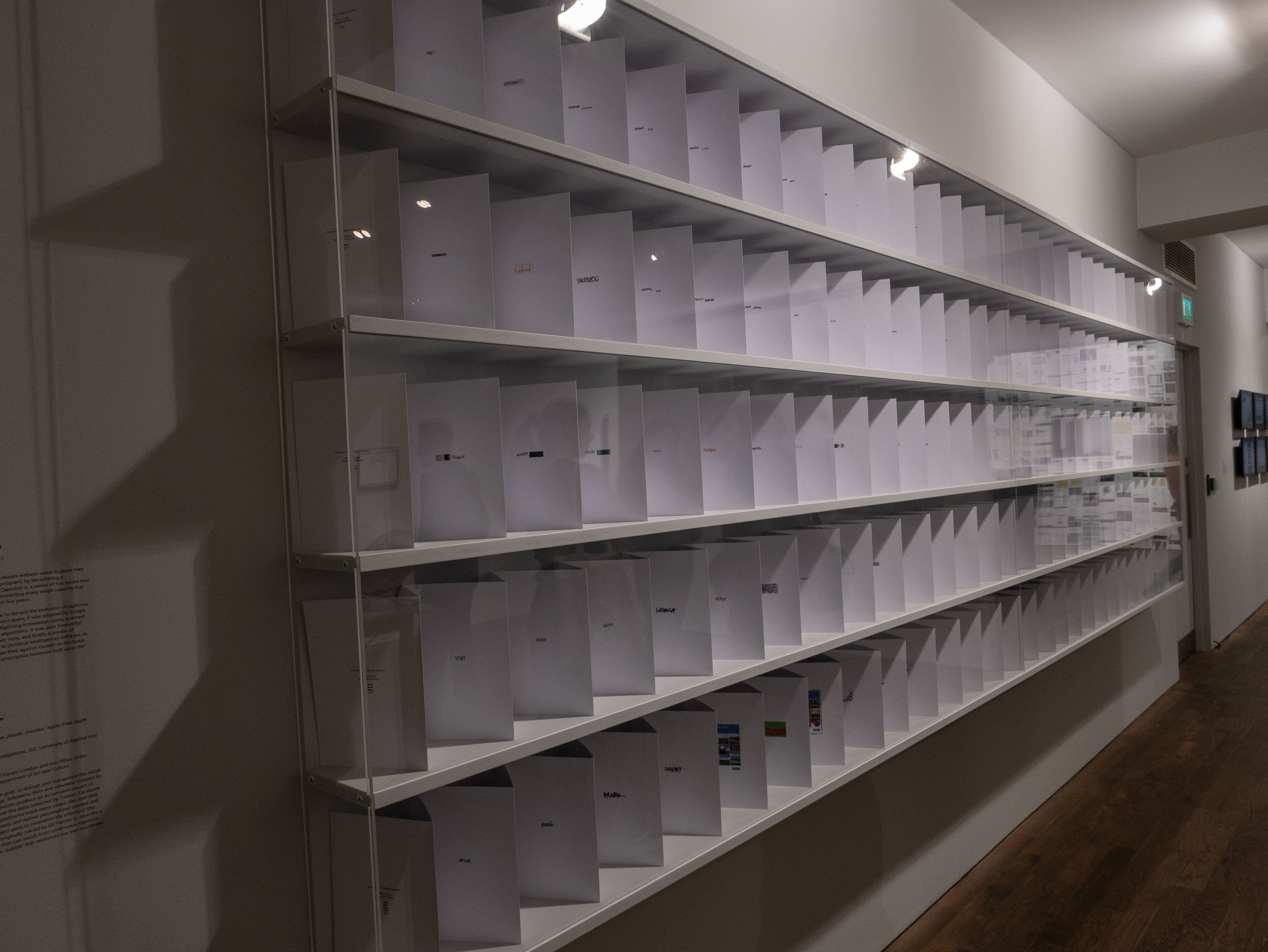

My second visit confirmed this impression and although there were several examples of novel ways of exhibiting work, and some interesting videos by groups experimenting with off grid lifestyles, there was nothing about the benefits of the digital imaging media which many currently enjoy. I initially felt that this was a missed opportunity to explore the democratisation of opportunities to use photography creatively, resulting from the ease of use and access to sophisticated technologies and sources of information but this would have needed a much larger platform and was clearly not the intention of the curators.

My second visit confirmed this impression and although there were several examples of novel ways of exhibiting work, and some interesting videos by groups experimenting with off grid lifestyles, there was nothing about the benefits of the digital imaging media which many currently enjoy. I initially felt that this was a missed opportunity to explore the democratisation of opportunities to use photography creatively, resulting from the ease of use and access to sophisticated technologies and sources of information but this would have needed a much larger platform and was clearly not the intention of the curators.

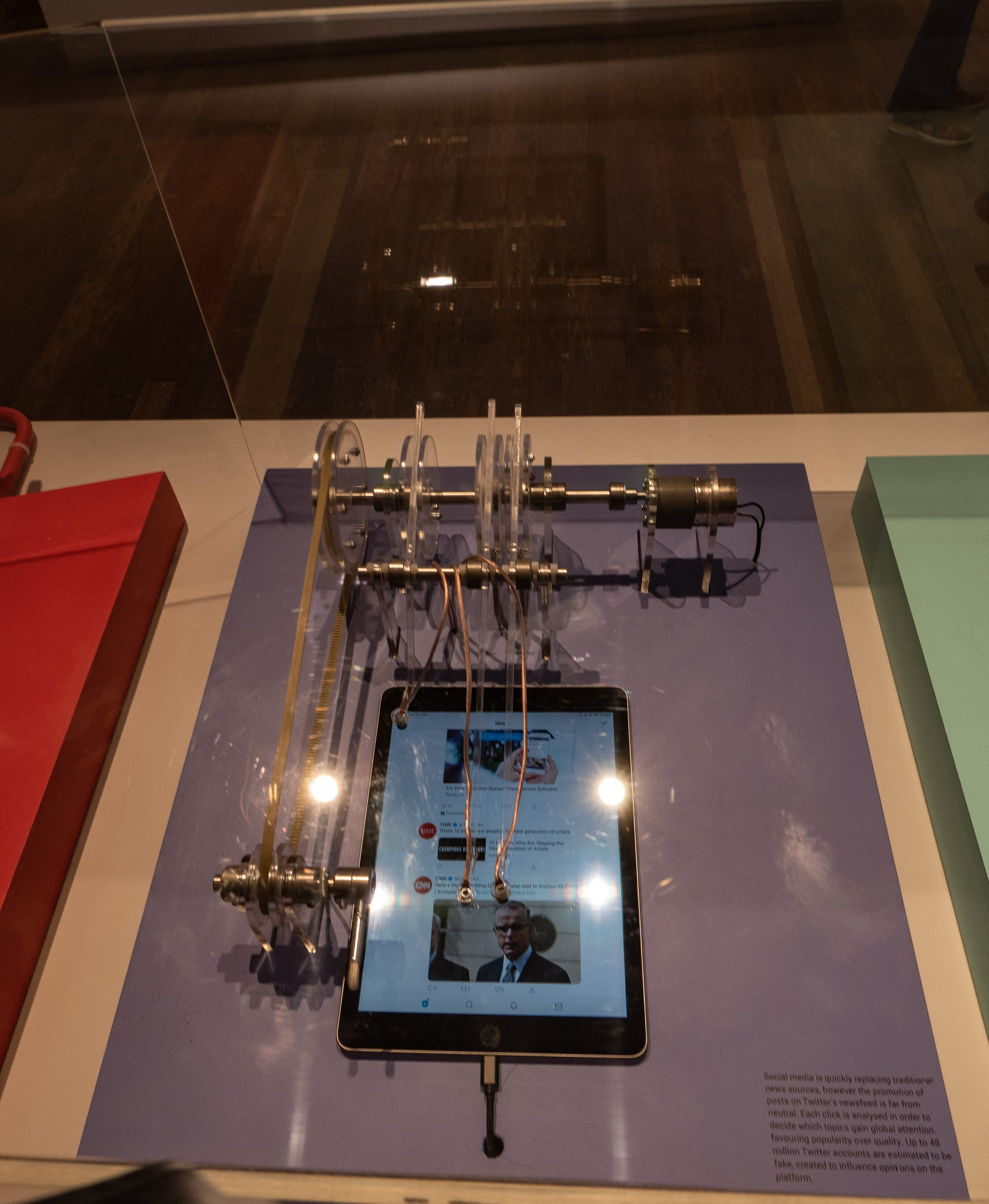

For photographers, the issues which give rise to imminent concern, online financial fraud, plagiarism or repeated recycling of cliched ideas, the rapid turnover of vast numbers of increasingly homogeneous imagery and the built in obsolescence of expensive digital hardware and software (with the failure of manufacturers to provide continuing support) are all well known but were not specifically addressed by the exhibition. Good research often leads to more questions than answers and this exhibition highlighted several new areas of concern, especially in relation to the practices of the large multi-national companies providing our online services but without offering any immediate solutions. All digital photographs of the exhibits used to illustrate this post captured in situ at the Photographers Gallery, London by the author.Featured Image: Photograph of the exhibit - 'The driver and the cameras' (Google street view camera operators), Emilio Vavarelli 2012.Further information about the exhibitors is available from: www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibition/all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internet

For photographers, the issues which give rise to imminent concern, online financial fraud, plagiarism or repeated recycling of cliched ideas, the rapid turnover of vast numbers of increasingly homogeneous imagery and the built in obsolescence of expensive digital hardware and software (with the failure of manufacturers to provide continuing support) are all well known but were not specifically addressed by the exhibition. Good research often leads to more questions than answers and this exhibition highlighted several new areas of concern, especially in relation to the practices of the large multi-national companies providing our online services but without offering any immediate solutions. All digital photographs of the exhibits used to illustrate this post captured in situ at the Photographers Gallery, London by the author.Featured Image: Photograph of the exhibit - 'The driver and the cameras' (Google street view camera operators), Emilio Vavarelli 2012.Further information about the exhibitors is available from: www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibition/all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internet