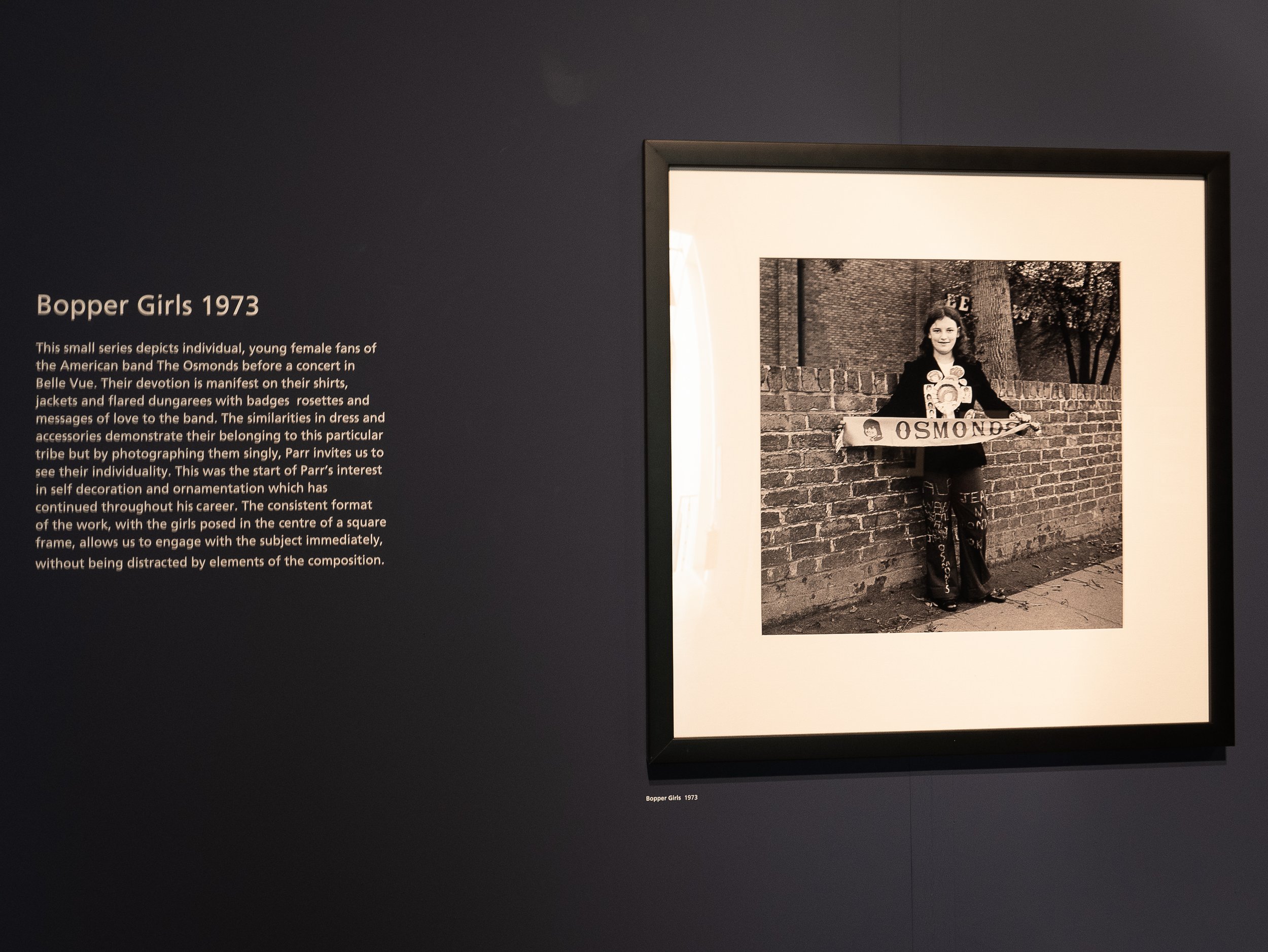

This exhibition currently showing at Manchester Art Gallery focuses on Martin Parr's long term engagement with the people of the city and the surrounding industrial towns of the North West, which form the region of Greater Manchester. From his first student projects in 1970, over a period of nearly fifty years, he has returned regularly and his work now constitutes a substantial documentary record of the changes in the fabric of city's buildings along with its' cultural and social development from an industrial region to modern twenty-first century metropolis.By concentrating on the lives of the inhabitants he has recorded the effects of on one hand, the social deprivation resulting from de-industrialization and on the other, the gentrification of parts of the city, which closely mirrors the changes seen in other major UK cities. The thread which runs through these projects is his ability to capture the warmth and resilience of the people he photographed along the way, especially those from the working class areas. His early black and white photographs are still resonant of the times they covered. His series from the psychiatric hospital in Prestwich are especially poignant and his medium format photographs of girl 'teenyboppers’ manage to capture a sense of the personalities of the teenagers as well as the period detail of their clothing. The layout of the exhibition seamlessly follows his switch to working in colour in the early 1980’s, making the change appear to fit logically with the ways in which that period is now usually remembered (colour in television screens, magazines and newspaper supplements, at that time becoming the norm). The colours recorded in the details of people's everyday lives; shop windows, home decor, clothing, are particularly resonant of the times.

His early black and white photographs are still resonant of the times they covered. His series from the psychiatric hospital in Prestwich are especially poignant and his medium format photographs of girl 'teenyboppers’ manage to capture a sense of the personalities of the teenagers as well as the period detail of their clothing. The layout of the exhibition seamlessly follows his switch to working in colour in the early 1980’s, making the change appear to fit logically with the ways in which that period is now usually remembered (colour in television screens, magazines and newspaper supplements, at that time becoming the norm). The colours recorded in the details of people's everyday lives; shop windows, home decor, clothing, are particularly resonant of the times. More than a few contemporary photographers (including myself) have commented that they find his more recent digital colour images less easy to relate to, which seems difficult to comprehend given that his working methods and subject matter have not significantly changed and the colours and clarity of detail in the images are if anything truer to life. Perhaps now we already know his work so well that there are now simply fewer surprises or the use of digital capture somehow lacks the resonance we felt looking at the earlier work with analogue materials. Alternatively could it be that these images are too close to what we see around us and in the media every day - does familiarity breed contempt? Perhaps if we are still here, we might respond to them more positively in another twenty years time.http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/martin-parr/

More than a few contemporary photographers (including myself) have commented that they find his more recent digital colour images less easy to relate to, which seems difficult to comprehend given that his working methods and subject matter have not significantly changed and the colours and clarity of detail in the images are if anything truer to life. Perhaps now we already know his work so well that there are now simply fewer surprises or the use of digital capture somehow lacks the resonance we felt looking at the earlier work with analogue materials. Alternatively could it be that these images are too close to what we see around us and in the media every day - does familiarity breed contempt? Perhaps if we are still here, we might respond to them more positively in another twenty years time.http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/martin-parr/

‘A Summer of Discovery in Wales: Aerial Archaeology and the Remarkable Heatwave of 2018’

January 29th 2019I went to this lecture, given by Dr Toby Driver on behalf of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales at Pontio in Bangor last night. He described the use of aerial photography during the surprisingly hot, dry period in late June and July last year when the cropmarks in the fields throughout Wales, revealed many sites of archaeological interest which have been buried under the ground for hundreds and in some cases thousands of years. These images of the outlines of sites which cannot normally be seen on the surface, included several completely new discoveries in areas previously unknown to contain any historical artefacts. They also revealed many of the recorded sites in unusually clear detail and revealed a number of new areas of potential interest in the land adjacent to them.The lecturer explained that the mechanism by which these cropmarks appear depends on the differential growth, ripening and drying out of the plants due to the amount of water held in the underlying soil. Where the layer of soil is deeper, for example where there have been ditches around fortified buildings or pits for waste, more water is retained and the growth remains lush and green, drying out and yellowing more slowly than the surrounding areas. Here the soil is shallow, over paved areas, roads or the footings of buildings, the crops run out of water and dry out more quickly. The unusual feature of last summer was the length of the period without any rainfall - the cropmarks normally disappear quickly after any rainfall and are also destroyed when they are harvested by the farmers (who need to do this before they spoil) or grazed by livestock. The drought provided the researchers with a three week interval allowing them 35 hours of flying time in which they made a total of 5700 digital exposures. They are still in the process of reviewing and analysing these photographs which can also involve enhancing the information from them in Photoshop, using tonal separation tools in the colour channels (concentrating on shades of greens and yellows) to produce remarkably detailed monochrome images. The cultures which created the structures and building outlines seen in the images range from prehistoric tribes, through the Celtic people of the Bronze and Iron Ages, the Roman Occupations and Mediaeval populations right up to the early part of the twentieth century. The structures seen include settlements and hut circles, burial mounds and iron age barrows, ditches, field systems and enclosures, Roman roads, forts, marching camps, villas and bath houses, mediaeval churches, monasteries and graveyards and training camps dating from the first world war (e.g. on the Kinmel Estate near Bodelwyddan). The researchers are particularly interested in the relatively poorly documented routes used by the Roman armies in subjugating the Silurian tribes in South Wales and the Ordovices and Deceangli in North Wales in the period between 47AD and the end of the first century and believe they have identified potential sites for several previously undocumented marching camps and new sections of the Roman road network. While these will need to confirmed by groundwork, geophysics and LIDAR imaging this appears to be a good example of the use of this highly specialised application of photography as a tool for ethnographic research.www.rcahmw.gov.uk (Cymraeg = www.cbhc.gov.uk)www.coflein.gov.ukThe images used to illustrate this post were taken by Dr Toby Driver and were retrieved from the website of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales who hold the Crown Copyright for them.

The cultures which created the structures and building outlines seen in the images range from prehistoric tribes, through the Celtic people of the Bronze and Iron Ages, the Roman Occupations and Mediaeval populations right up to the early part of the twentieth century. The structures seen include settlements and hut circles, burial mounds and iron age barrows, ditches, field systems and enclosures, Roman roads, forts, marching camps, villas and bath houses, mediaeval churches, monasteries and graveyards and training camps dating from the first world war (e.g. on the Kinmel Estate near Bodelwyddan). The researchers are particularly interested in the relatively poorly documented routes used by the Roman armies in subjugating the Silurian tribes in South Wales and the Ordovices and Deceangli in North Wales in the period between 47AD and the end of the first century and believe they have identified potential sites for several previously undocumented marching camps and new sections of the Roman road network. While these will need to confirmed by groundwork, geophysics and LIDAR imaging this appears to be a good example of the use of this highly specialised application of photography as a tool for ethnographic research.www.rcahmw.gov.uk (Cymraeg = www.cbhc.gov.uk)www.coflein.gov.ukThe images used to illustrate this post were taken by Dr Toby Driver and were retrieved from the website of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales who hold the Crown Copyright for them.