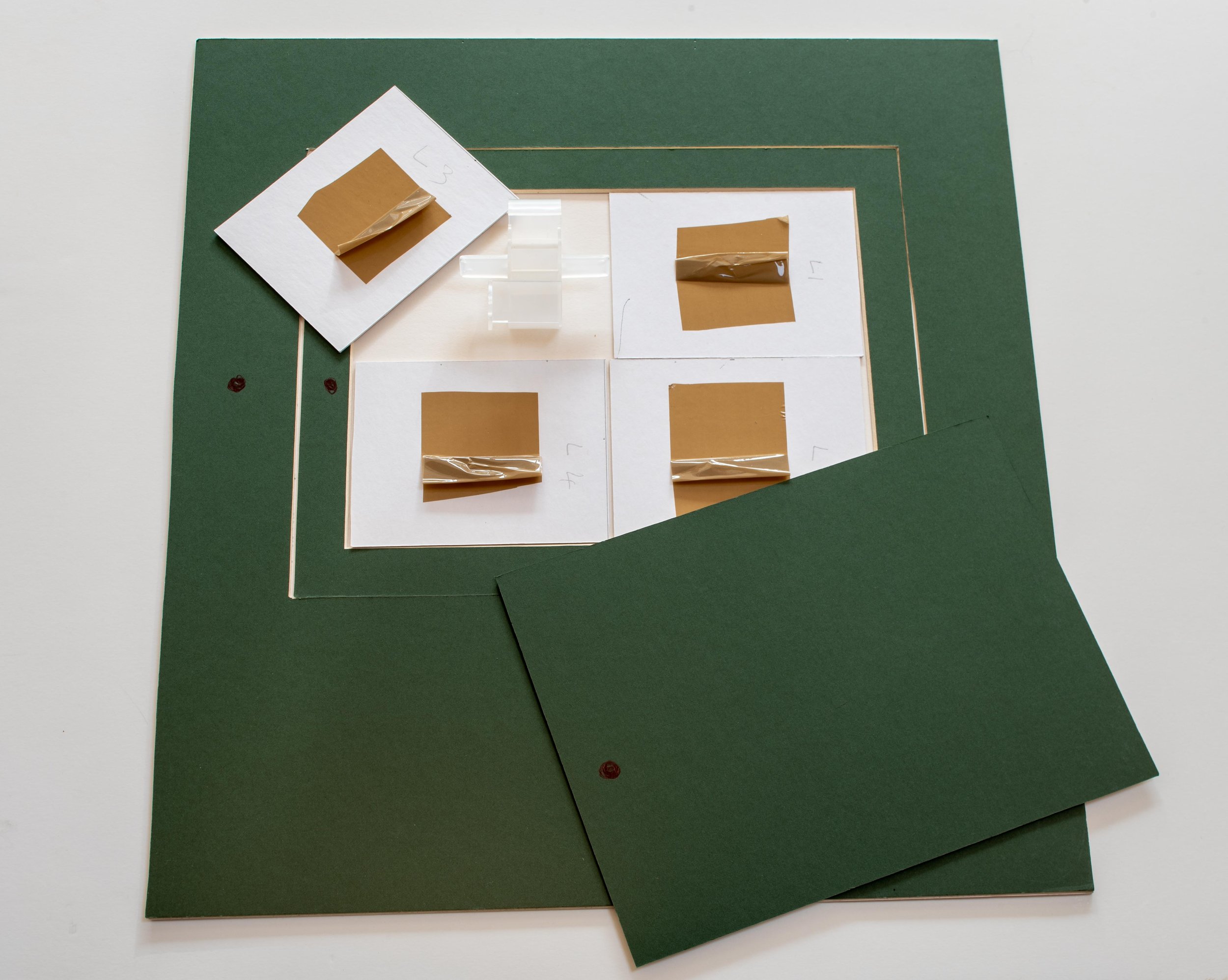

It is expected that a competent photographer should be capable of producing carefully exposed, precisely focused, technically perfect images. Learning the skills set required to master the controls of the camera can lead to a fixation on exposure and sharpness, a constant imperative that this must be done 'correctly', which in turn may constrain the development of personal visual expression (Ulrich, 2018). One way of balancing these conflicting processes, arriving at an equipoise between obsession with technique and freedom of expression, could be to concentrate on the basic elements, defined by Angela Faris Belt as constituting the 'grammar of photographic language'; framing and borders, quality of focus (using lenses and apertures to control depth of field), time and motion (determined by shutter speed) and the physical media used to present the final image (Belt, 2008).Patricia Townsend discusses this in her essay in 'Photographers and Research', stressing the importance of being able to respond to all aspects of the medium (camera, processing of film, digital process, printing technique or darkroom equipment), and then listen to what the medium has to 'say'. In the essay, she quotes photographer Liz Rideal as follows: "it's about the happy accident but it's also about recognising something when it's coming to the surface" (Townsend, 2017). The photogram below could be considered as and example of an accidental discovery arising from the challenge of working with colour photographic paper, which being polychromatic has to be handled in complete darkness. I was attempting to produce an image with a single plastic insert, using a seemingly 'simple' makeshift masking technique with scrap cardboard, to make four separate exposures and create a futuristic grid like structure. I gave up when it proved impossible to align the plastic accurately in the dark and the cardboard masks kept slipping between exposures.

I was attempting to produce an image with a single plastic insert, using a seemingly 'simple' makeshift masking technique with scrap cardboard, to make four separate exposures and create a futuristic grid like structure. I gave up when it proved impossible to align the plastic accurately in the dark and the cardboard masks kept slipping between exposures. On reviewing the dried prints the following morning, I realised that the randomly overlapping placement of the card and the plastic insert had produced different levels of exposure (particularly in the bottom right hand corner), creating unexpected shapes with different tones of the same colour. The resulting image is almost certainly more interesting, than it would have been if the technique had worked 'correctly' and I now know (roughly) how to repeat the effect.Psychoanalysis has identified that the freedom to be creative is dependent on the ability to enter a state of mind which is similar to that found in children (and adults) engaging in uninhibited play (Winnicott, 1971). Is it possible to create these happy accidents or do we have to keep working, trying to find ways around the limitations of our processes and materials and hope that we can recognise them when they eventually come along?Belt A F (2008). 'The Elements of Photography'. Oxford; Focal Press (Elsevier Inc.), p XIX.Townsend P (2017). 'Between Inner and Outer Worlds'. In: Photographers and Research, ed. Read S and Simmons M; Abingdon, Oxon., Focal Press (Routledge). pp 211-212.Ulrich D (2018). 'Zen Camera'; New York, Watson-Guptill Publications, p 140.Winnicott D W (1971). 'Playing and Reality'. Abingdon, Oxon., Routledge. p 71.

On reviewing the dried prints the following morning, I realised that the randomly overlapping placement of the card and the plastic insert had produced different levels of exposure (particularly in the bottom right hand corner), creating unexpected shapes with different tones of the same colour. The resulting image is almost certainly more interesting, than it would have been if the technique had worked 'correctly' and I now know (roughly) how to repeat the effect.Psychoanalysis has identified that the freedom to be creative is dependent on the ability to enter a state of mind which is similar to that found in children (and adults) engaging in uninhibited play (Winnicott, 1971). Is it possible to create these happy accidents or do we have to keep working, trying to find ways around the limitations of our processes and materials and hope that we can recognise them when they eventually come along?Belt A F (2008). 'The Elements of Photography'. Oxford; Focal Press (Elsevier Inc.), p XIX.Townsend P (2017). 'Between Inner and Outer Worlds'. In: Photographers and Research, ed. Read S and Simmons M; Abingdon, Oxon., Focal Press (Routledge). pp 211-212.Ulrich D (2018). 'Zen Camera'; New York, Watson-Guptill Publications, p 140.Winnicott D W (1971). 'Playing and Reality'. Abingdon, Oxon., Routledge. p 71.