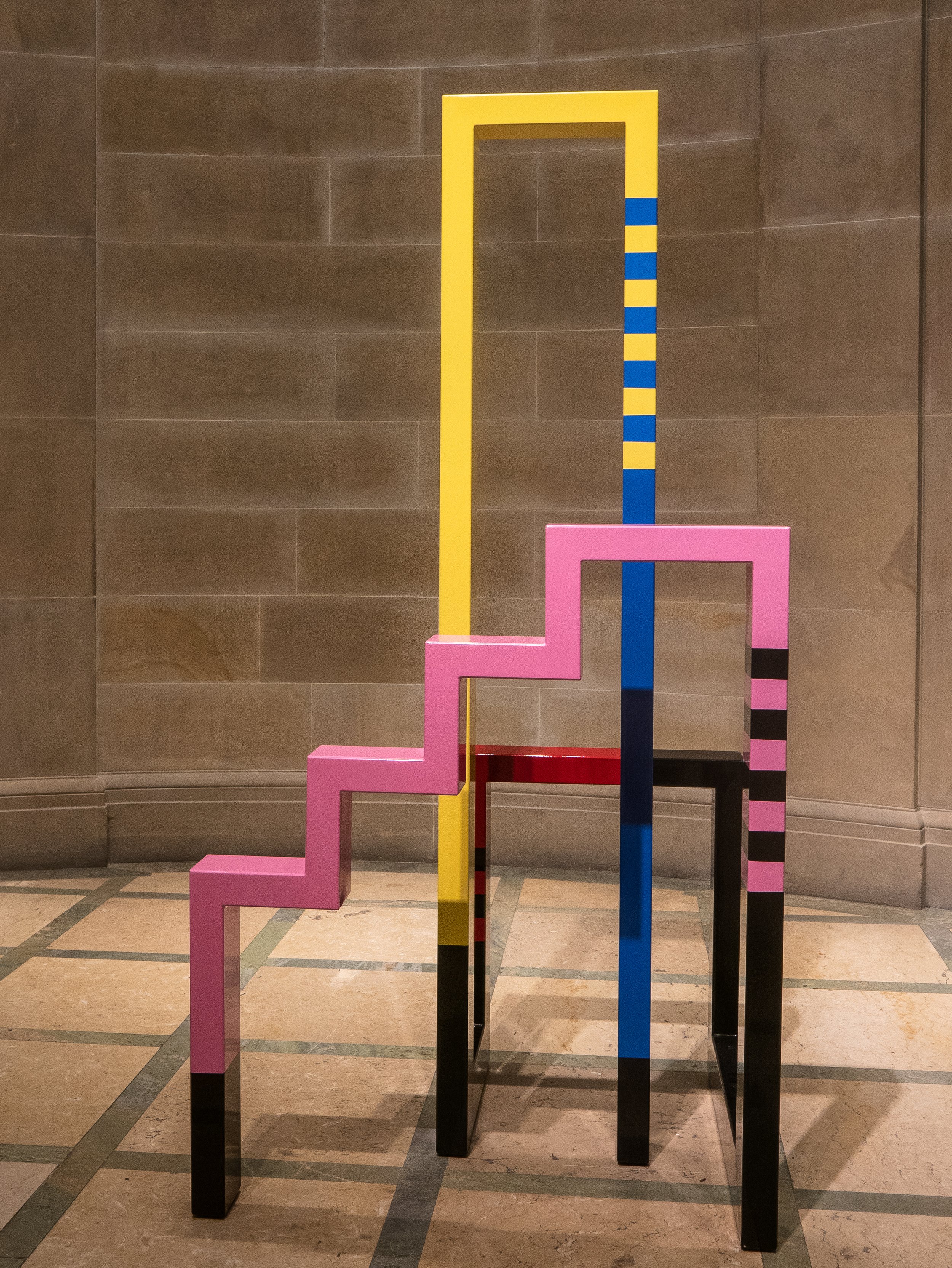

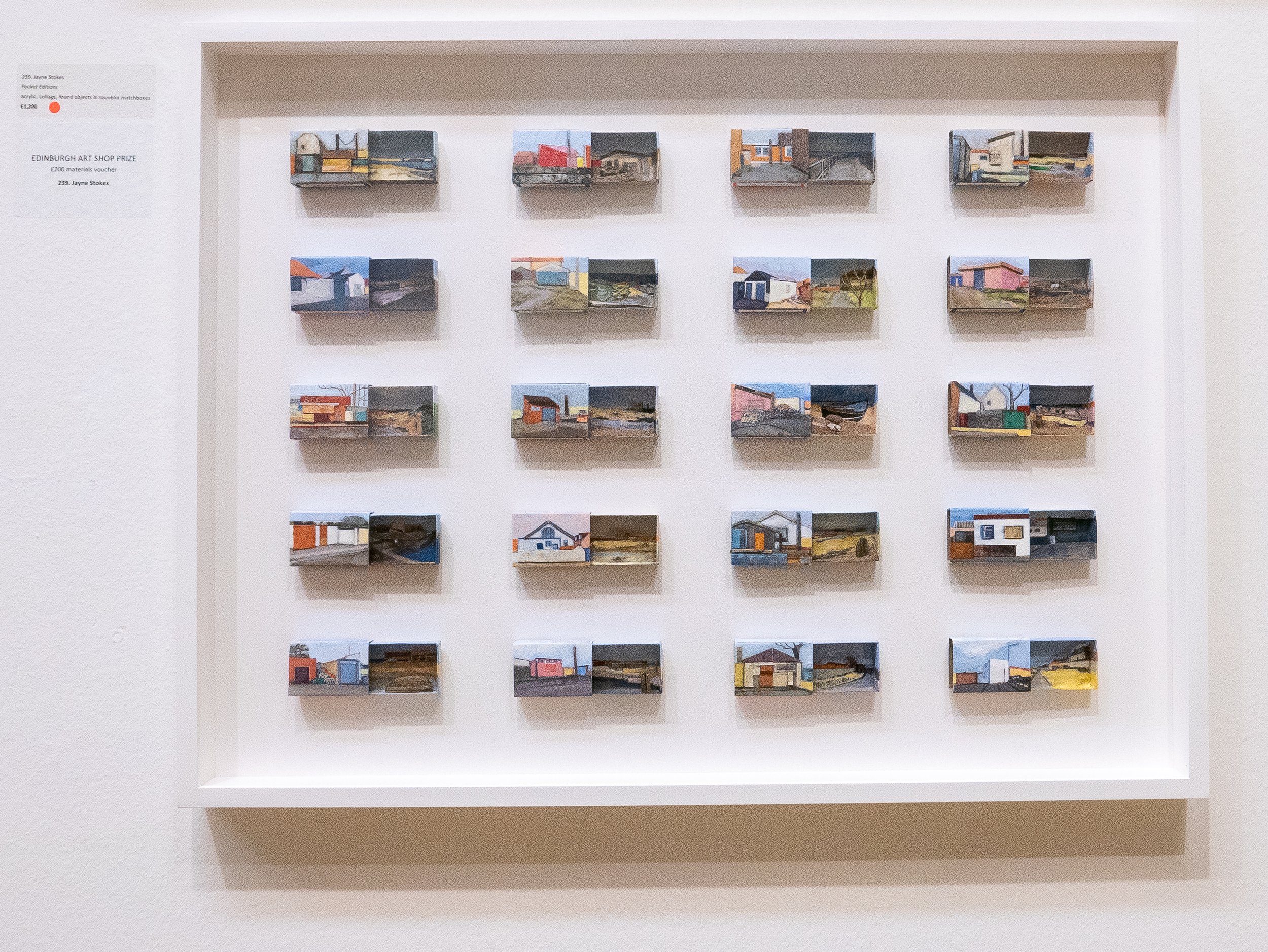

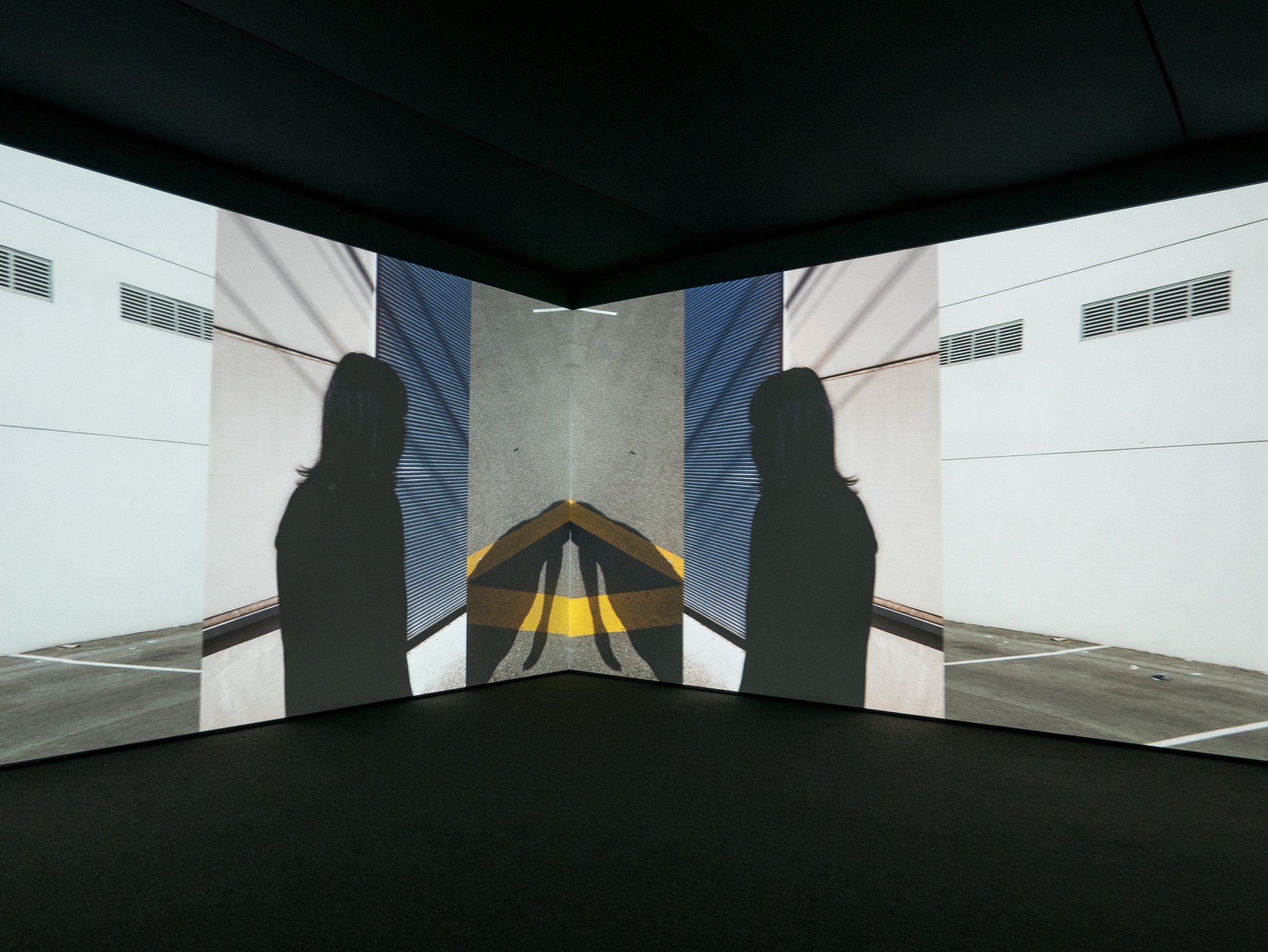

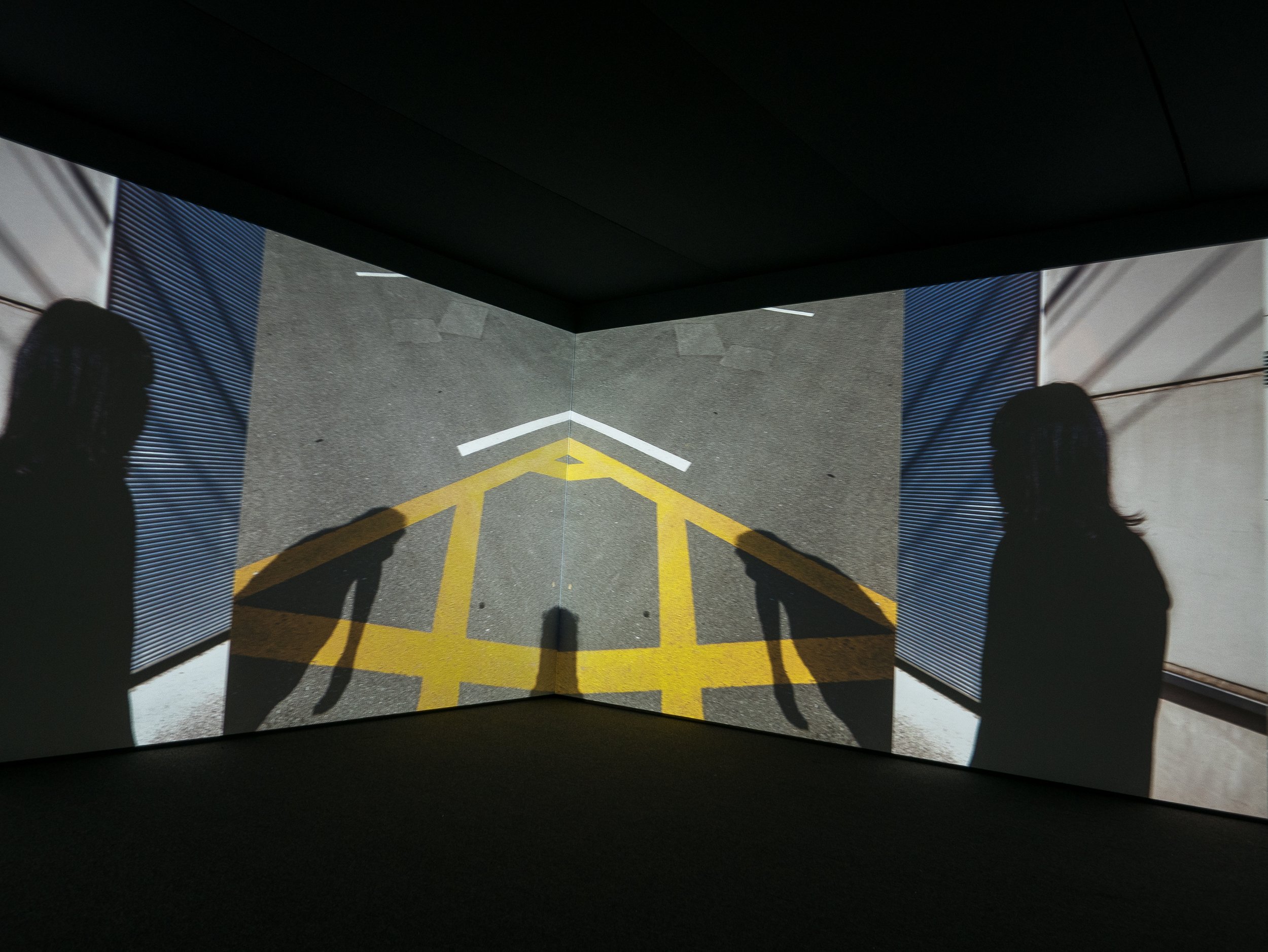

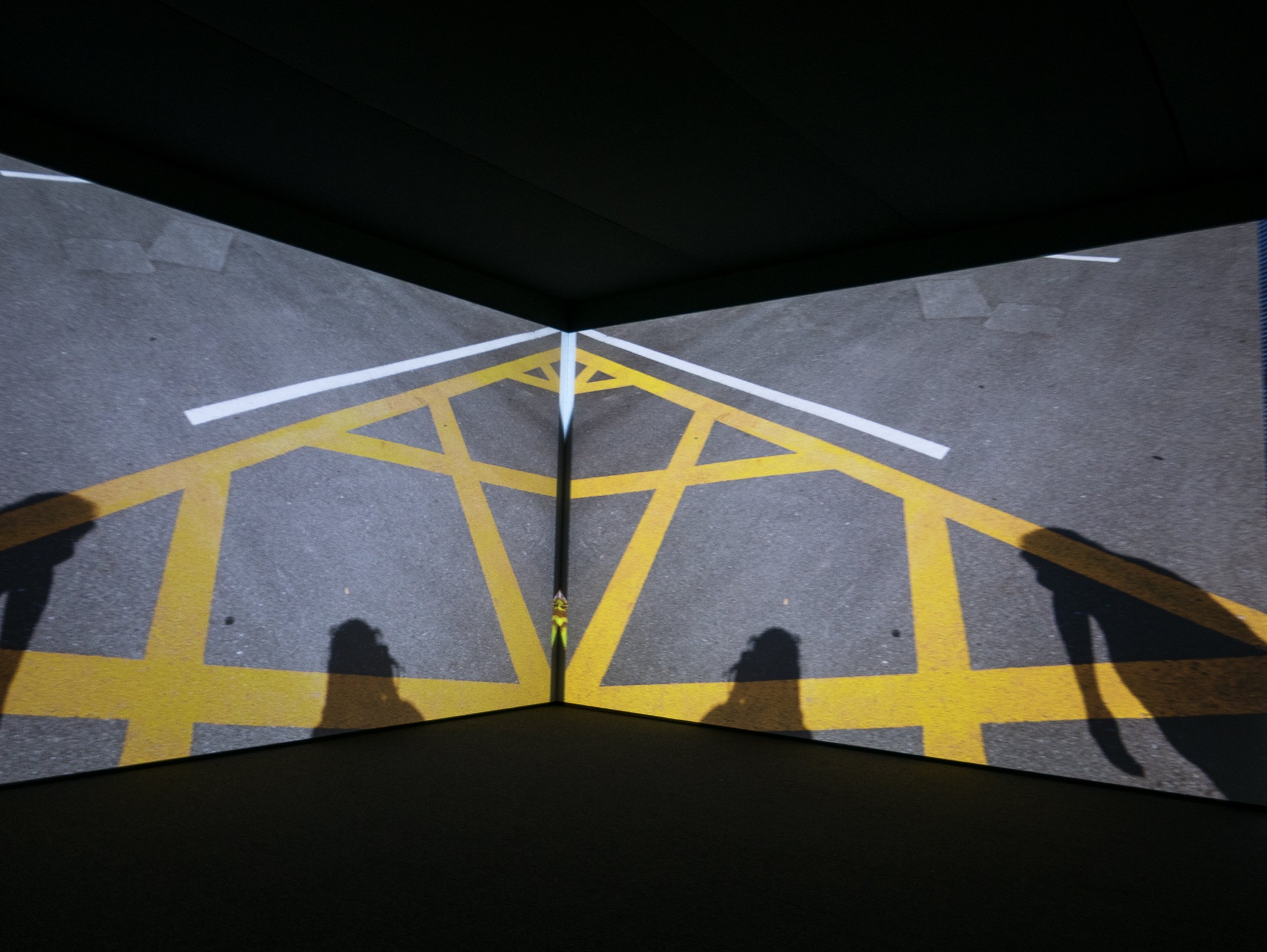

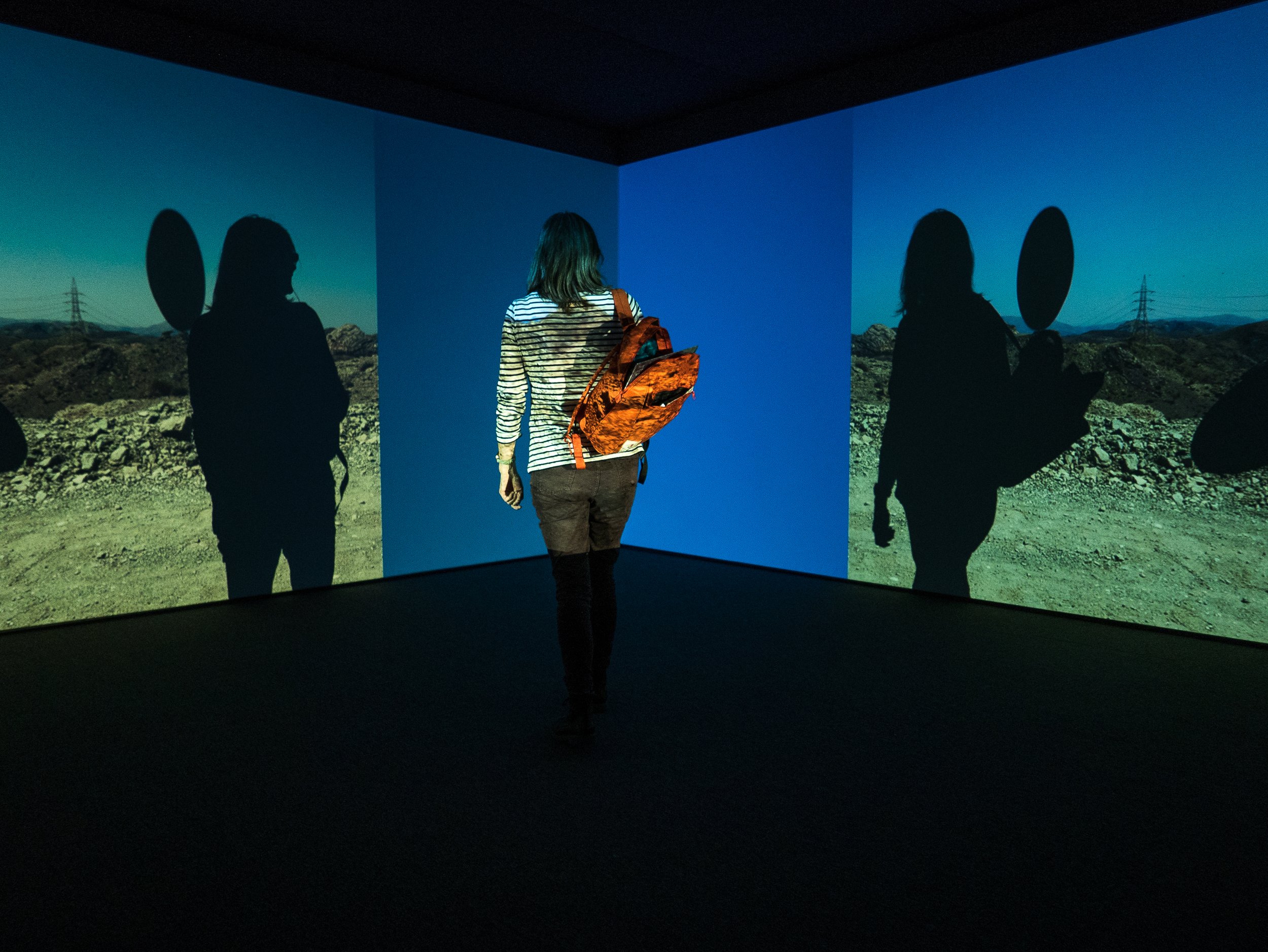

The 193rd Annual Exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, is showing currently in the National Gallery of Scotland on Princess Street, Edinburgh until 11th December, 2019. Entry is free and a generous selection of the work on show can be found on their very useful website. Most of the exhibits are paintings but there were also a reasonable number of sculptures, some installations and video art. The two rooms devoted to the architectural entries were particularly interesting.My own photographs below show some examples of just a few of the exhibits which particularly caught my eye.

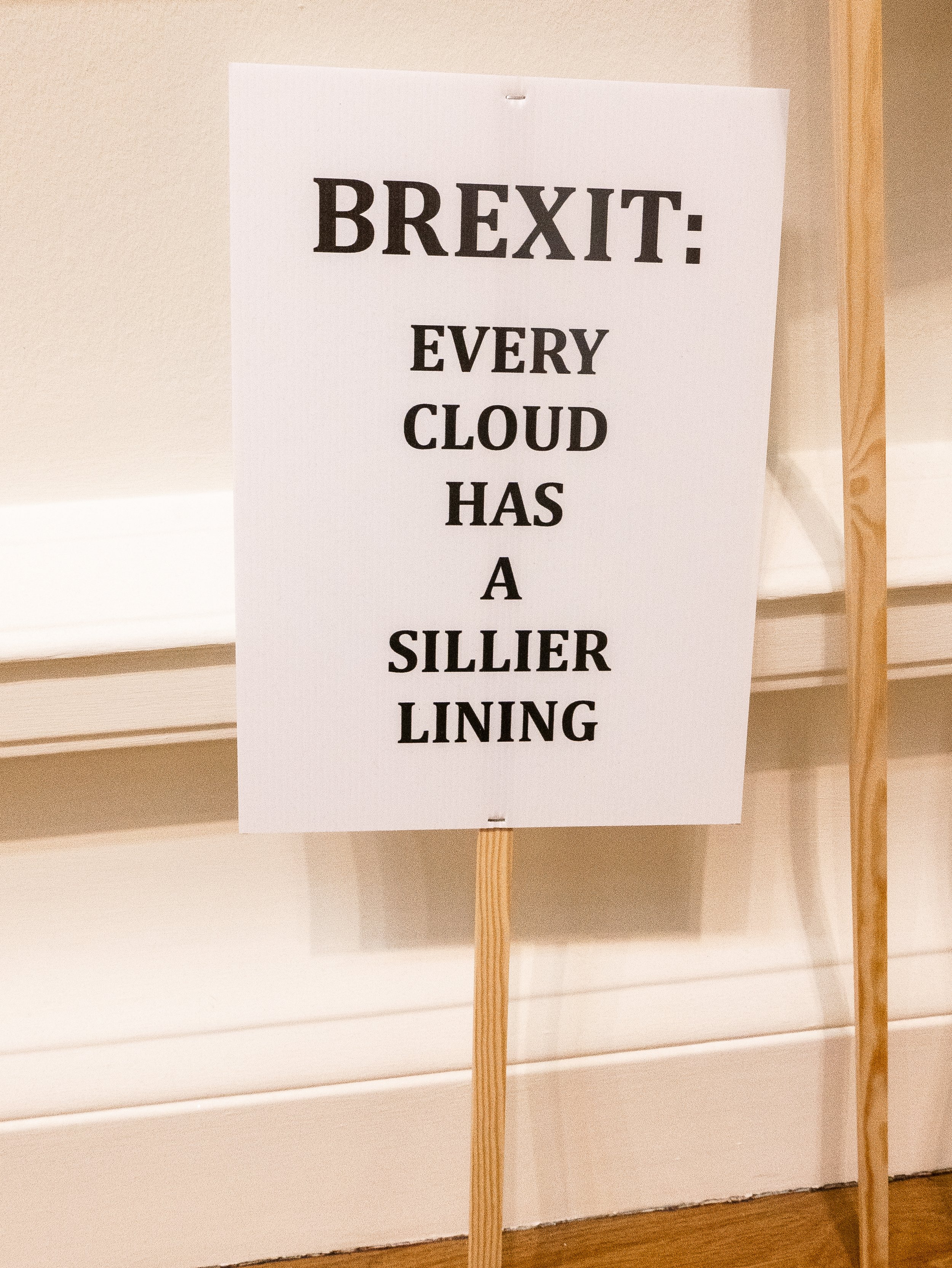

As a comment on the current state of play in UK politics, it seemed appropriate to show a closer look at the detail in this installation piece. The protester below who was photographed outside the gallery on the following morning appears to agree.

As a comment on the current state of play in UK politics, it seemed appropriate to show a closer look at the detail in this installation piece. The protester below who was photographed outside the gallery on the following morning appears to agree. https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/exhibitions/rsa-annual-exhibition-2019/

https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/exhibitions/rsa-annual-exhibition-2019/

Generating interest in plastic waste

In trying to highlight the more serious issues created by careless disposal of waste plastic much of which ends up in the sea, I have attempted to make photographs of waste plastic on beaches but felt that most of the images were disappointingly ineffectual (boring). The image above and the featured image were made at Traeth Cymyran on Anglesey a few weeks after a storm at Holyhead harbour destroyed the pontoons in the marina which used blocks of polystyrene for buoyancy, spreading fragments like that in the photograph for many miles along the coast. A huge variety of non-biodegradable materials are washed onto beaches, even in the most remote areas, like the island off the Atlantic coast of the North West of Ireland in the example below.

In trying to highlight the more serious issues created by careless disposal of waste plastic much of which ends up in the sea, I have attempted to make photographs of waste plastic on beaches but felt that most of the images were disappointingly ineffectual (boring). The image above and the featured image were made at Traeth Cymyran on Anglesey a few weeks after a storm at Holyhead harbour destroyed the pontoons in the marina which used blocks of polystyrene for buoyancy, spreading fragments like that in the photograph for many miles along the coast. A huge variety of non-biodegradable materials are washed onto beaches, even in the most remote areas, like the island off the Atlantic coast of the North West of Ireland in the example below. I have followed with interest, the amount of media coverage recently given to the environmental impact of waste plastic and one contemporary photographer who has published several very effective bodies of work in this area, is Mandy Barker (born 1964). In an extensive interview with Mike Simmons in 'Photographers and Research', she explained that she also initially tried to make her photographs in situ, where it washed up on the beach but felt that the familiarity of these images resulted in people being unlikely to engage with them. She found that by taking the objects into the studio and photographing them in saturated colour against a solid black background, she could create the impression of an alien life form deep in the sea, suspended underwater. For her first series 'Indefinite' she used solitary objects but in her subsequent projects 'Soup' and 'Shoal', she used digital montages of multiple samples of plastic objects collected from beaches, varying their size in the image to create an impression of perspective depth and positioning them in ways which mimicked the circulation of underwater currents.The other element which adds impact to her images is her use of imaginative captioning, giving viewers limited but factual contextual detail; sometimes a grid reference, sometimes an indication of the type of plastic debris or how long it would take to degrade. She also went to great lengths to ensure the accuracy of her information, by collaborating and making extensive field trips with oceanographic scientists and has presented her photographs at prestigious ecology conferences. For a series of images titled 'PENALTY', made to exploit the publicity surrounding the 2014 F.I.F.A. World Cup, she used a social media call-out for donations from the public, to collect and photograph 769 plastic footballs collected from 144 beaches in 41 countries around the world.A retrospective of her work is currently on show at the Royal Photographic Society in Bristol and 'Beyond Drifting' her most recent series of photographs, is featured this month in Black and White Photography magazine. These abstract monochrome images are captioned with pseodo-Latin species names and framed in a circular mount, to mimic the appearance of photographs of plankton taken using a microscope but are in reality plastic debris, flowers, toys, tricycle wheels, a Barbie dolls arm and a plastic yoke from a six-pack. In the accompanying article she explains that the images were taken with old film cameras on out-of-date grainy film, with movement blur which on the first occasion, occurred when in the darkness of her studio, she inadvertently knocked into the tank in which they were suspended during a long exposure, a 'happy accident' which she quickly recognised and exploited to make the rest of the series.Her work has moved on a long way from the simple photographs of artifacts on the beach demonstrating the value of her extensive research, her collaborations with experts in the field and her willingness to experiment with different formats to produce photographs of plastic waste, which are powerful enough to draw in viewers and in the process encourage them to engage with an issue of serious significance.

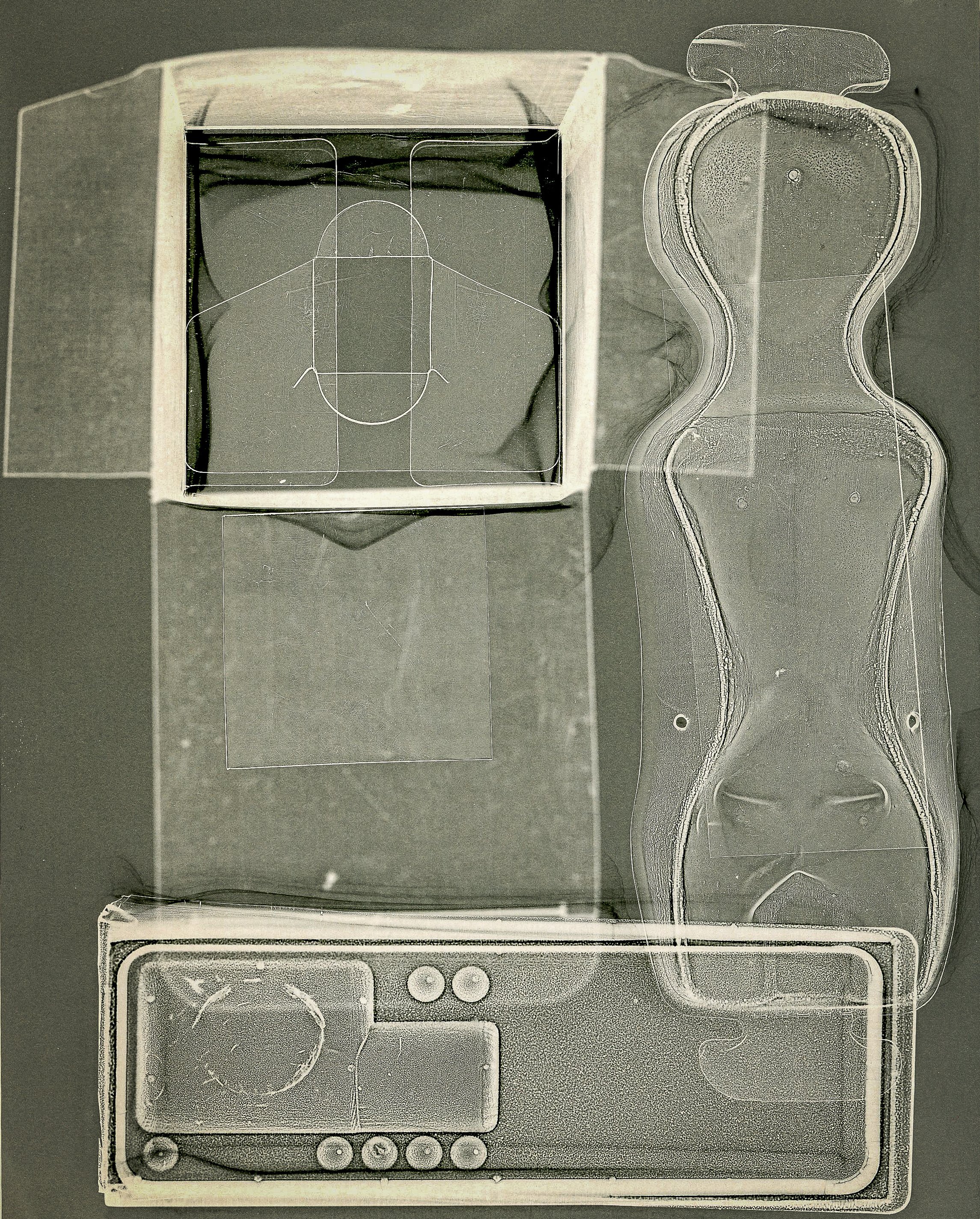

I have followed with interest, the amount of media coverage recently given to the environmental impact of waste plastic and one contemporary photographer who has published several very effective bodies of work in this area, is Mandy Barker (born 1964). In an extensive interview with Mike Simmons in 'Photographers and Research', she explained that she also initially tried to make her photographs in situ, where it washed up on the beach but felt that the familiarity of these images resulted in people being unlikely to engage with them. She found that by taking the objects into the studio and photographing them in saturated colour against a solid black background, she could create the impression of an alien life form deep in the sea, suspended underwater. For her first series 'Indefinite' she used solitary objects but in her subsequent projects 'Soup' and 'Shoal', she used digital montages of multiple samples of plastic objects collected from beaches, varying their size in the image to create an impression of perspective depth and positioning them in ways which mimicked the circulation of underwater currents.The other element which adds impact to her images is her use of imaginative captioning, giving viewers limited but factual contextual detail; sometimes a grid reference, sometimes an indication of the type of plastic debris or how long it would take to degrade. She also went to great lengths to ensure the accuracy of her information, by collaborating and making extensive field trips with oceanographic scientists and has presented her photographs at prestigious ecology conferences. For a series of images titled 'PENALTY', made to exploit the publicity surrounding the 2014 F.I.F.A. World Cup, she used a social media call-out for donations from the public, to collect and photograph 769 plastic footballs collected from 144 beaches in 41 countries around the world.A retrospective of her work is currently on show at the Royal Photographic Society in Bristol and 'Beyond Drifting' her most recent series of photographs, is featured this month in Black and White Photography magazine. These abstract monochrome images are captioned with pseodo-Latin species names and framed in a circular mount, to mimic the appearance of photographs of plankton taken using a microscope but are in reality plastic debris, flowers, toys, tricycle wheels, a Barbie dolls arm and a plastic yoke from a six-pack. In the accompanying article she explains that the images were taken with old film cameras on out-of-date grainy film, with movement blur which on the first occasion, occurred when in the darkness of her studio, she inadvertently knocked into the tank in which they were suspended during a long exposure, a 'happy accident' which she quickly recognised and exploited to make the rest of the series.Her work has moved on a long way from the simple photographs of artifacts on the beach demonstrating the value of her extensive research, her collaborations with experts in the field and her willingness to experiment with different formats to produce photographs of plastic waste, which are powerful enough to draw in viewers and in the process encourage them to engage with an issue of serious significance. I have been making close-up photographs of the textural detail in waste packaging intermittently for several years. My original motivation for this was simply the challenge of trying to find something aesthetically pleasing in a mundane subject, which would not normally be considered as 'photogenic'. I also enjoy using isolation of detail, distortion of scale or unusual lighting to create something ambiguous, leaving the viewer unsure of what they are looking at. The fact that clear or translucent forms of packaging are very effective materials for creating photograms in the darkroom was a fortuitous coincidence, which has taken my own work in a potentially more interesting direction. Could this be an alternative approach to raising awareness by investigating the factors, other than their contents and practical convenience, which attract consumers to continue using them.Barker M (2019). 'Mandy Barker Photography' (Photographers website), Accessed on 2 May 2019 at: https://mandy-barker.com/Calder T (2019). 'Beyond Drifting' (Interview with Mandy Barker). Black and White Photography, Lewes East Sussex; Guild of Master Craftsman Publications. Issue No. 229, pp 28 - 35.Royal Photographic Society (2019). 'Mandy Barker: Altered Ocean Exhibition', Open: 4 April - 23 June 2019. Location: RPS House, Bristol. Information Accessed 2 May 2019 at: www.rps.org/exhibitions-and-competitions/mandy-barkerShukman D (2019). 'Plastic in the Ocean' (BBC iplayer film), Accessed on 14 April 2019 at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p069vjw6Plastic-in-the-OceanSimmons M (2017). 'Case Sudy: Mandy Barker'. In: Read S and Simmons M 'Photographers and Research', Abingdon Oxon. and New York, Routledge, pp 126 - 139.

I have been making close-up photographs of the textural detail in waste packaging intermittently for several years. My original motivation for this was simply the challenge of trying to find something aesthetically pleasing in a mundane subject, which would not normally be considered as 'photogenic'. I also enjoy using isolation of detail, distortion of scale or unusual lighting to create something ambiguous, leaving the viewer unsure of what they are looking at. The fact that clear or translucent forms of packaging are very effective materials for creating photograms in the darkroom was a fortuitous coincidence, which has taken my own work in a potentially more interesting direction. Could this be an alternative approach to raising awareness by investigating the factors, other than their contents and practical convenience, which attract consumers to continue using them.Barker M (2019). 'Mandy Barker Photography' (Photographers website), Accessed on 2 May 2019 at: https://mandy-barker.com/Calder T (2019). 'Beyond Drifting' (Interview with Mandy Barker). Black and White Photography, Lewes East Sussex; Guild of Master Craftsman Publications. Issue No. 229, pp 28 - 35.Royal Photographic Society (2019). 'Mandy Barker: Altered Ocean Exhibition', Open: 4 April - 23 June 2019. Location: RPS House, Bristol. Information Accessed 2 May 2019 at: www.rps.org/exhibitions-and-competitions/mandy-barkerShukman D (2019). 'Plastic in the Ocean' (BBC iplayer film), Accessed on 14 April 2019 at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p069vjw6Plastic-in-the-OceanSimmons M (2017). 'Case Sudy: Mandy Barker'. In: Read S and Simmons M 'Photographers and Research', Abingdon Oxon. and New York, Routledge, pp 126 - 139.

A happy accident

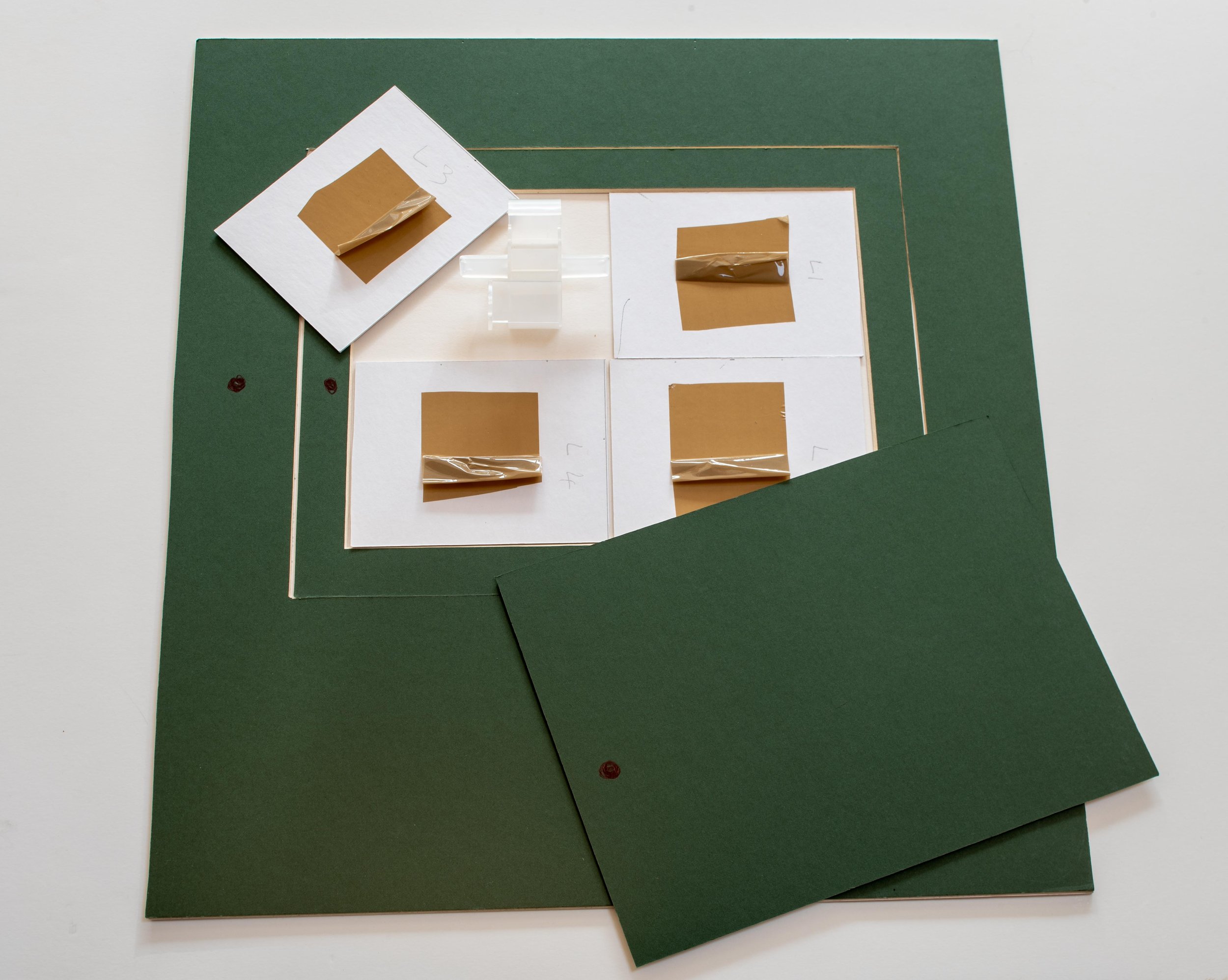

It is expected that a competent photographer should be capable of producing carefully exposed, precisely focused, technically perfect images. Learning the skills set required to master the controls of the camera can lead to a fixation on exposure and sharpness, a constant imperative that this must be done 'correctly', which in turn may constrain the development of personal visual expression (Ulrich, 2018). One way of balancing these conflicting processes, arriving at an equipoise between obsession with technique and freedom of expression, could be to concentrate on the basic elements, defined by Angela Faris Belt as constituting the 'grammar of photographic language'; framing and borders, quality of focus (using lenses and apertures to control depth of field), time and motion (determined by shutter speed) and the physical media used to present the final image (Belt, 2008).Patricia Townsend discusses this in her essay in 'Photographers and Research', stressing the importance of being able to respond to all aspects of the medium (camera, processing of film, digital process, printing technique or darkroom equipment), and then listen to what the medium has to 'say'. In the essay, she quotes photographer Liz Rideal as follows: "it's about the happy accident but it's also about recognising something when it's coming to the surface" (Townsend, 2017). The photogram below could be considered as and example of an accidental discovery arising from the challenge of working with colour photographic paper, which being polychromatic has to be handled in complete darkness. I was attempting to produce an image with a single plastic insert, using a seemingly 'simple' makeshift masking technique with scrap cardboard, to make four separate exposures and create a futuristic grid like structure. I gave up when it proved impossible to align the plastic accurately in the dark and the cardboard masks kept slipping between exposures.

I was attempting to produce an image with a single plastic insert, using a seemingly 'simple' makeshift masking technique with scrap cardboard, to make four separate exposures and create a futuristic grid like structure. I gave up when it proved impossible to align the plastic accurately in the dark and the cardboard masks kept slipping between exposures. On reviewing the dried prints the following morning, I realised that the randomly overlapping placement of the card and the plastic insert had produced different levels of exposure (particularly in the bottom right hand corner), creating unexpected shapes with different tones of the same colour. The resulting image is almost certainly more interesting, than it would have been if the technique had worked 'correctly' and I now know (roughly) how to repeat the effect.Psychoanalysis has identified that the freedom to be creative is dependent on the ability to enter a state of mind which is similar to that found in children (and adults) engaging in uninhibited play (Winnicott, 1971). Is it possible to create these happy accidents or do we have to keep working, trying to find ways around the limitations of our processes and materials and hope that we can recognise them when they eventually come along?Belt A F (2008). 'The Elements of Photography'. Oxford; Focal Press (Elsevier Inc.), p XIX.Townsend P (2017). 'Between Inner and Outer Worlds'. In: Photographers and Research, ed. Read S and Simmons M; Abingdon, Oxon., Focal Press (Routledge). pp 211-212.Ulrich D (2018). 'Zen Camera'; New York, Watson-Guptill Publications, p 140.Winnicott D W (1971). 'Playing and Reality'. Abingdon, Oxon., Routledge. p 71.

On reviewing the dried prints the following morning, I realised that the randomly overlapping placement of the card and the plastic insert had produced different levels of exposure (particularly in the bottom right hand corner), creating unexpected shapes with different tones of the same colour. The resulting image is almost certainly more interesting, than it would have been if the technique had worked 'correctly' and I now know (roughly) how to repeat the effect.Psychoanalysis has identified that the freedom to be creative is dependent on the ability to enter a state of mind which is similar to that found in children (and adults) engaging in uninhibited play (Winnicott, 1971). Is it possible to create these happy accidents or do we have to keep working, trying to find ways around the limitations of our processes and materials and hope that we can recognise them when they eventually come along?Belt A F (2008). 'The Elements of Photography'. Oxford; Focal Press (Elsevier Inc.), p XIX.Townsend P (2017). 'Between Inner and Outer Worlds'. In: Photographers and Research, ed. Read S and Simmons M; Abingdon, Oxon., Focal Press (Routledge). pp 211-212.Ulrich D (2018). 'Zen Camera'; New York, Watson-Guptill Publications, p 140.Winnicott D W (1971). 'Playing and Reality'. Abingdon, Oxon., Routledge. p 71.

Colour theory - Itten and Albers

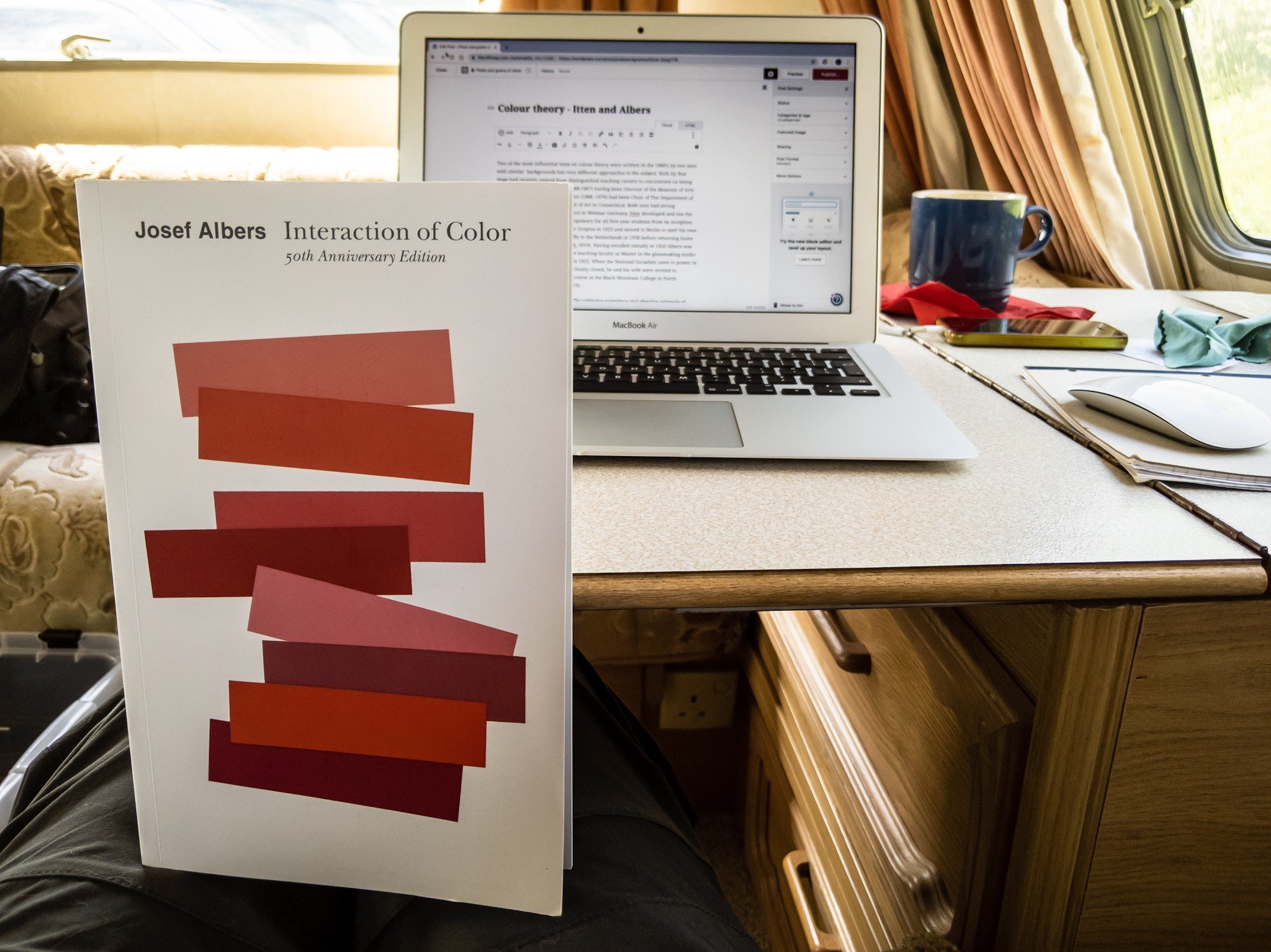

Two of the most influential texts on colour theory were written in the 1960's by two men with similar backgrounds but very different approaches to the subject. Both by that stage had recently retired from distinguished teaching careers to concentrate on being working artists, Johannes Itten (1888-1967) having been Director of the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zurich and Josef Albers (1888 -1976), Chair of The Department of Design at the Yale University School of Art in Connecticut. Both men had strong connections with the Bauhaus School in Weimar Germany. Itten developed and ran the Preliminary Course which was compulsory for all first year students from its inception in 1919 until he fell out with Walter Gropius in 1923 and moved to Berlin to start his own school of design. He moved briefly to the Netherlands in 1938 before returning home to Switzerland later that year (Art Directory Gmbh, 2019). Having enrolled initially in 1920 Albers was the first Bauhaus student to join the teaching faculty as a Master in the glassmaking studio, at the time the school moved to Dessau in 1925. When the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933 and the Bauhaus finally closed, he and his wife were invited to establish the inaugural visual arts course at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina (albersfoundation.org, 2019).  On first impression Art of Color : The subjective experience and objective rationale of color by Johannes Itten has the look and feel of a beautifully illustrated traditional large format textbook. The early chapters explain colour physics, with brief descriptions of the colour spectrum, the light forming wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation which are focused via the optical mechanism of the eye (cornea and lens) to be captured by the photosensitive cells in the retina (the sensor), then transmitted to the optical cortex of the brain to be perceived as a continually refreshed image. Subsequent chapters move on from these objective principles to his own theories (expanding on earlier work by Adolf Holzel with whom he had trained in Stuttgart), which explore how our subjective perception can be influenced by emotional and symbolic factors in combination with the visual interactions of complementary and contrasting colours (bauhaus100.com, 2019). "Color perception is the psycho-physiological reality as distinguished from the physio-chemical reality of color" (Itten, 1963). His explanations of the significance of these phenomena are illustrated by reference to a series of paintings ranging chronologically from eighth century religious paintings, through the work of the European old masters, to the abstract modern art of Klee (a fellow Master in the Bauhaus teaching faculty), Mondrian and Picasso. The book is worth reading for these comprehensive insightful explanations alone.The approach taken by Albers in the more modest looking Interaction of Color is that of a practical course manual for students in a colour theory classroom, presented as a series of exercises using swatches of coloured papers, designed to demonstrate rather than simply describe how interacting colours are perceived. The illustrations linked to each chapter are presented separately from the exercises, the aim being that students should first try to reproduce them for themselves, presumably as a more effective way of learning. Many of the exercises recreate apparent optical illusions (colour deceptions) but in doing so, provide rational explanations for complex phenomena and like Itten, demonstrating that "in visual perception there is a discrepancy between physical fact and psychic effect" (Albers, 1963). His demonstrations of the use of the effect of colour intensity (brightness) to show how an identical swatch of colour is perceived differently depending on the background it is placed against (page 8) and the phenomenon of the after image (page 22) are simple but remarkably effective.

On first impression Art of Color : The subjective experience and objective rationale of color by Johannes Itten has the look and feel of a beautifully illustrated traditional large format textbook. The early chapters explain colour physics, with brief descriptions of the colour spectrum, the light forming wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation which are focused via the optical mechanism of the eye (cornea and lens) to be captured by the photosensitive cells in the retina (the sensor), then transmitted to the optical cortex of the brain to be perceived as a continually refreshed image. Subsequent chapters move on from these objective principles to his own theories (expanding on earlier work by Adolf Holzel with whom he had trained in Stuttgart), which explore how our subjective perception can be influenced by emotional and symbolic factors in combination with the visual interactions of complementary and contrasting colours (bauhaus100.com, 2019). "Color perception is the psycho-physiological reality as distinguished from the physio-chemical reality of color" (Itten, 1963). His explanations of the significance of these phenomena are illustrated by reference to a series of paintings ranging chronologically from eighth century religious paintings, through the work of the European old masters, to the abstract modern art of Klee (a fellow Master in the Bauhaus teaching faculty), Mondrian and Picasso. The book is worth reading for these comprehensive insightful explanations alone.The approach taken by Albers in the more modest looking Interaction of Color is that of a practical course manual for students in a colour theory classroom, presented as a series of exercises using swatches of coloured papers, designed to demonstrate rather than simply describe how interacting colours are perceived. The illustrations linked to each chapter are presented separately from the exercises, the aim being that students should first try to reproduce them for themselves, presumably as a more effective way of learning. Many of the exercises recreate apparent optical illusions (colour deceptions) but in doing so, provide rational explanations for complex phenomena and like Itten, demonstrating that "in visual perception there is a discrepancy between physical fact and psychic effect" (Albers, 1963). His demonstrations of the use of the effect of colour intensity (brightness) to show how an identical swatch of colour is perceived differently depending on the background it is placed against (page 8) and the phenomenon of the after image (page 22) are simple but remarkably effective. I am working my way through both of these books at present and am only just beginning to get to get to grips with the subject. The featured image below is my digital photograph of a step in a bathroom ceiling which is painted entirely white.

I am working my way through both of these books at present and am only just beginning to get to get to grips with the subject. The featured image below is my digital photograph of a step in a bathroom ceiling which is painted entirely white. The colours have been produced through manipulation of the RAW file in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, simply by accentuating (albeit grossly) the existing colour casts in the image. The sunlit area is warm in tone, producing the primary colour yellow when enhanced, while the tone of the area in shadow is cool forming the complementary blue when accentuated. These casts are barely perceptible in the original photograph and not normally 'seen' by the naked eye as, knowing that the paint is white, our brain 'corrects' this for us. Photographers working in colour, in trying to obtain colours which are true to life, usually correct these casts when they become apparent. This experiment for me suggests that in reality the colours are already there, which would mean that in striving to obtain tones which will be perceived as 'true', we may in fact be perpetrating a deception. Albers J (1963). 'Interaction of Color'. New Haven, Yale University Press. (My edition of this is the Fiftieth Anniversary (4th) Edition of the paperback version, still in print and published in 2013)albersfoundation.org (2019). Josef and Anni Albers biographies. Online, Accessed 27 April, 2019 at: www.albersfoundation.org/artists/biographies/Art Directory Gmbh (2019). Johannes Itten Biography. Online, Accessed 2 May, 2019 at: www.johannes-itten.combauhaus100.com (2019) Johannes Itten. Online, Accessed 2 May 2019 at: https://www.bauhaus100.com/the-bauhaus/people/masters-and-teachers/johannes-itten/Itten J (1973) 'Art of Color : The subjective experience and objective rationale of color'. New York, John Wiley and Sons Inc. (first published in Germany in 1961 by Otto Maier Verlag)

The colours have been produced through manipulation of the RAW file in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, simply by accentuating (albeit grossly) the existing colour casts in the image. The sunlit area is warm in tone, producing the primary colour yellow when enhanced, while the tone of the area in shadow is cool forming the complementary blue when accentuated. These casts are barely perceptible in the original photograph and not normally 'seen' by the naked eye as, knowing that the paint is white, our brain 'corrects' this for us. Photographers working in colour, in trying to obtain colours which are true to life, usually correct these casts when they become apparent. This experiment for me suggests that in reality the colours are already there, which would mean that in striving to obtain tones which will be perceived as 'true', we may in fact be perpetrating a deception. Albers J (1963). 'Interaction of Color'. New Haven, Yale University Press. (My edition of this is the Fiftieth Anniversary (4th) Edition of the paperback version, still in print and published in 2013)albersfoundation.org (2019). Josef and Anni Albers biographies. Online, Accessed 27 April, 2019 at: www.albersfoundation.org/artists/biographies/Art Directory Gmbh (2019). Johannes Itten Biography. Online, Accessed 2 May, 2019 at: www.johannes-itten.combauhaus100.com (2019) Johannes Itten. Online, Accessed 2 May 2019 at: https://www.bauhaus100.com/the-bauhaus/people/masters-and-teachers/johannes-itten/Itten J (1973) 'Art of Color : The subjective experience and objective rationale of color'. New York, John Wiley and Sons Inc. (first published in Germany in 1961 by Otto Maier Verlag)

Fingertips in Time - John Hedley

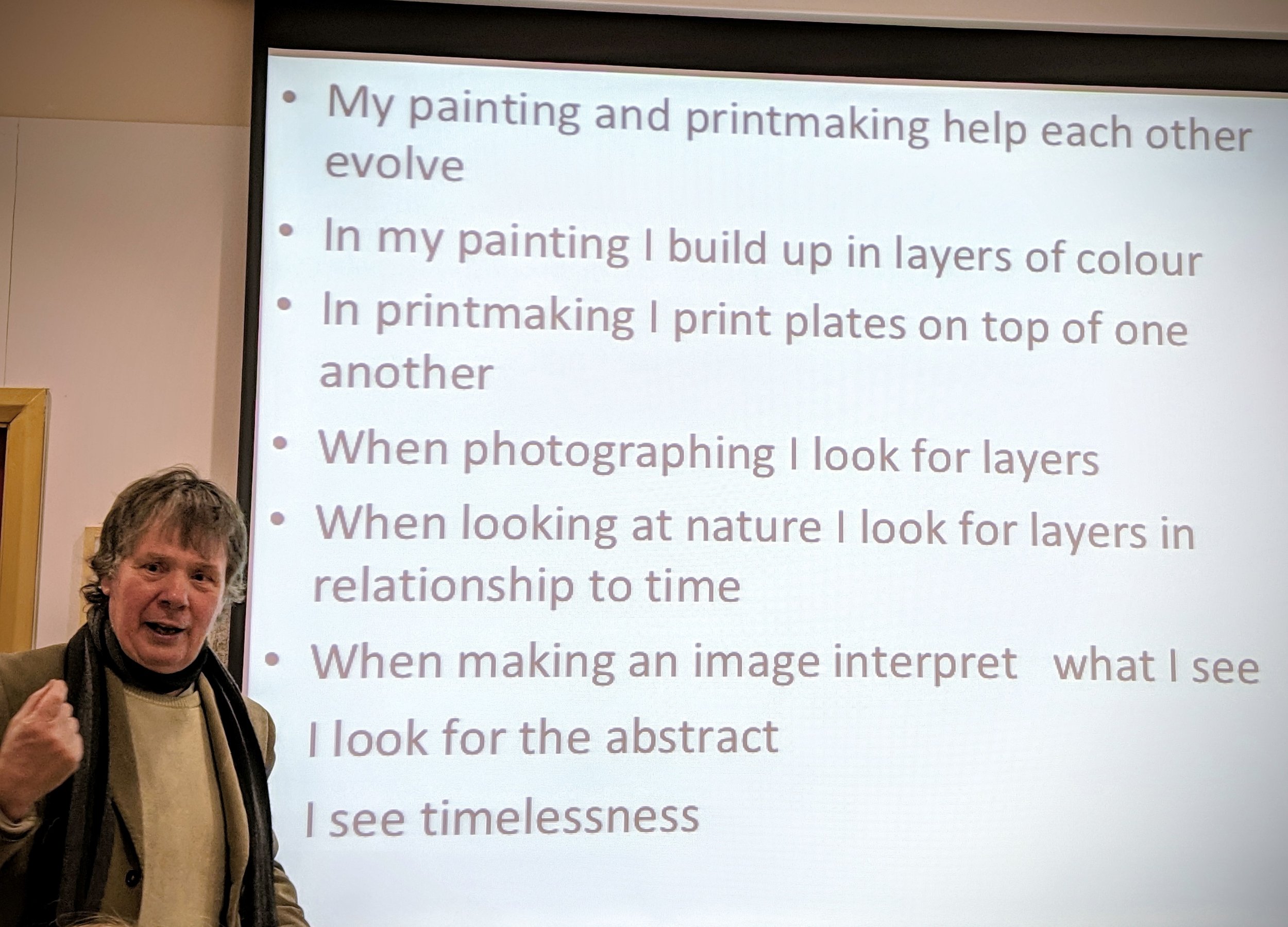

The painter and printmaker John Hedley gave a talk on the work in his exhibition 'Fingertips in Time' at Oriel Colwyn on Thursday 7th March 2019. The exhibited images fall into two series, one of trees presented as monochrome prints which looked almost like charcoal sketches and the other, a series of multicoloured print studies of volcanic rock formations from two sites, one at Llandwyn Island on Anglesey and the other in Crete. John talked about the techniques he used in making these and also more extensively about his work in general including his paintings, sculpture and work with mixed media. My interest in his processes relates to his use of digital camera photographs as the starting point and how he went about transforming these into intaglio prints. He explained that he prints the photographs as a positive image at high resolution (600 dpi bitmapped) onto acetate, using an A3 inkjet photo quality printer. The acetate is then exposed in a UV light box (Natgraph) onto a photopolymer etching plate (Solar Plate), which when processed and prepared (polished) can be inked up for printing onto dampened paper in a press. He explained that until recently, he had been wary of using photography as he felt this was almost like cheating. When he started using a digital SLR camera he discovered that the learning process was more complicated than he had anticipated; the main difficulty being obtaining a perfect tonal range which would be compatible with his printmaking processes. After a fair amount of "learning by mistakes" he has found that photography and image processing (layering in Photoshop) is now influencing his painting which has become "more abstract, in a round about way". He feels the main difference between most photographers and painters is that photographers feel they need to know what the end result will be at the time they press the shutter - i.e. classic 'pre-visualisation' as advocated by Ansel Adams (Schaefer, 1992) and the f64 group (and most photographers since then). In his printmaking, especially with multiple layers of coloured inks, he seldom knows what it will look like when finished and part of the process of abstraction is that the image evolves layer by layer, as it is being made.

He explained that until recently, he had been wary of using photography as he felt this was almost like cheating. When he started using a digital SLR camera he discovered that the learning process was more complicated than he had anticipated; the main difficulty being obtaining a perfect tonal range which would be compatible with his printmaking processes. After a fair amount of "learning by mistakes" he has found that photography and image processing (layering in Photoshop) is now influencing his painting which has become "more abstract, in a round about way". He feels the main difference between most photographers and painters is that photographers feel they need to know what the end result will be at the time they press the shutter - i.e. classic 'pre-visualisation' as advocated by Ansel Adams (Schaefer, 1992) and the f64 group (and most photographers since then). In his printmaking, especially with multiple layers of coloured inks, he seldom knows what it will look like when finished and part of the process of abstraction is that the image evolves layer by layer, as it is being made. Expanding on this, he explained that in deciding what to photograph he looks for the the most obscure and abstract things he can find, often now looking in nature for visual representations of layers; one tree in front of others, shadows on rocks or sand, layers in dead wood or rock formations, layers in time. In interpreting what he can see, he is taking from nature then playing and abstracting from it. He described this process as "being like building with Lego - start with the finished object - take it apart then re-build it - it will look similar but not exactly the same".To my surprise, I found that I had more in common with his approach than I had expected. In discussion with the audience, he talked of shadows in art as having ambiguity, transience - similar to the feelings I have been trying to capture in my photographs of shadows. I had not previously grasped the significance of layers but in many of my images, that could be what gives them the impression of texture. I felt comfortable with his explanations of abstraction, a concept I have had difficulty fully understanding previously. He is clearly happy now using a hybrid of digital photography and traditional printing, feeding contemporary technology into long established analogue processes. He is going to be in Greece for the next couple of months but has offered to let some of us visit his studio to share his technical knowledge. Having never seen photo-etching in practice or intaglio prints being made, I still have some difficulty in understanding exactly how it works and this is now on my list to do over the summer. I am sure that the learning curve for developing his printmaking skills was much steeper and longer than it took him to get what he needed from digital photography but I am still interested in printing digital negatives on acetate for use with historical U-V light based photographic processes and his advice on file preparation and printing technique could be invaluable.His final comment on his acceptance of photography as a tool for image making was to concede that "the mobile phone has become the sketch-book of the 21st century".The images used to illustrate this post were captured on my mobile phone camera.Schaefer JP (1999) 'Visualisation: The Art of Seeing a Photograph' In: Ansel Adams Guide - Basic Techniques of Photography Book (1); Revised edition, Boston-New York-London, Little, Brown and Company, pp 131-134.

Expanding on this, he explained that in deciding what to photograph he looks for the the most obscure and abstract things he can find, often now looking in nature for visual representations of layers; one tree in front of others, shadows on rocks or sand, layers in dead wood or rock formations, layers in time. In interpreting what he can see, he is taking from nature then playing and abstracting from it. He described this process as "being like building with Lego - start with the finished object - take it apart then re-build it - it will look similar but not exactly the same".To my surprise, I found that I had more in common with his approach than I had expected. In discussion with the audience, he talked of shadows in art as having ambiguity, transience - similar to the feelings I have been trying to capture in my photographs of shadows. I had not previously grasped the significance of layers but in many of my images, that could be what gives them the impression of texture. I felt comfortable with his explanations of abstraction, a concept I have had difficulty fully understanding previously. He is clearly happy now using a hybrid of digital photography and traditional printing, feeding contemporary technology into long established analogue processes. He is going to be in Greece for the next couple of months but has offered to let some of us visit his studio to share his technical knowledge. Having never seen photo-etching in practice or intaglio prints being made, I still have some difficulty in understanding exactly how it works and this is now on my list to do over the summer. I am sure that the learning curve for developing his printmaking skills was much steeper and longer than it took him to get what he needed from digital photography but I am still interested in printing digital negatives on acetate for use with historical U-V light based photographic processes and his advice on file preparation and printing technique could be invaluable.His final comment on his acceptance of photography as a tool for image making was to concede that "the mobile phone has become the sketch-book of the 21st century".The images used to illustrate this post were captured on my mobile phone camera.Schaefer JP (1999) 'Visualisation: The Art of Seeing a Photograph' In: Ansel Adams Guide - Basic Techniques of Photography Book (1); Revised edition, Boston-New York-London, Little, Brown and Company, pp 131-134.

Elucidation or obfuscation: a reflection on academic writing styles.

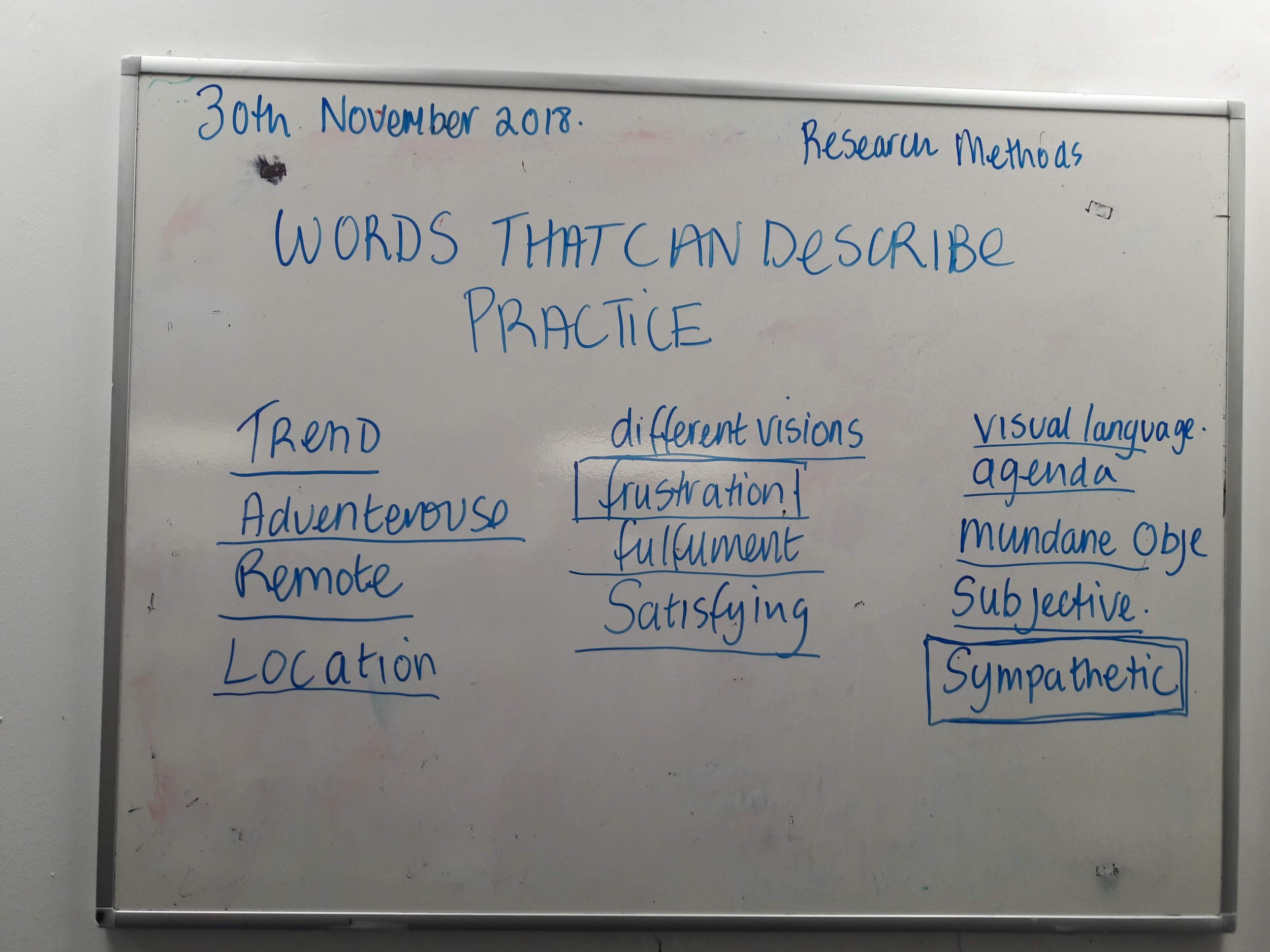

The ability to adopt an 'academic' style of writing is a recognised requirement for any degree level research report and students soon discover that a good thesaurus is an invaluable tool for finding novel words, with which they can present their thoughts concisely but also precisely. Academic literature could be considered as one of the last remaining bastions protecting our languages from the phenomenon of 'dumbing down'. If a single specific word could replace a phrase or most of a sentence then it seems logical to utilise it. The problem with using relatively obscure terminology is that many people will never have encountered these words and find it necessary to refer to a dictionary to comprehend them. Their resulting perception of an author who uses technical or grandiose language, could generate a sense of frustration sufficient to discourage the reader from continuing any further, which would become counter-productive. The importance of using appropriate language was considered in our tutorial on auto-ethnographic research on 30th November. In writing for other people, if the aim is to explain a complex concept in comprehensive detail, while avoiding unnecessary verbosity, this requirement for clarity but also brevity is potentially contradictory. Slight miscalculation of the perceived intellectual capacity of the intended audience may create a risk that the excessive use of what to some becomes incomprehensible jargon, will to them equate with elitism, designed to preclude their participation. In others, the contrary perception of apparently being talked down to, may generate an equally negative effect. My ambiguous personal views in this respect, derive from my experience as a clinician, guiding patients through complex medical dilemmas, where effective communication was essential. I discovered that it was important to vary the level at which the discussion was pitched to where the individual patient was comfortable but in general, the more complex the issues, the greater the need for less obscure language.While this should not be a dilemma in an academic setting, one consequence of my past experiences is a (possibly irrational) sense of trying to appear to be intellectually ostentatious resulting in a strong desire to avoid this. Resolution of this will entail finding a balance between my compulsive tendency to oversimplification in the form of over-elaborate description and my need to get back into the habit of using appropriately formal academic terminology. Fortunately, I feel that I am developing a better sense of realising this degree of equipoise in the visual language of my photography, hence the featured image chosen as the header for this post.

The importance of using appropriate language was considered in our tutorial on auto-ethnographic research on 30th November. In writing for other people, if the aim is to explain a complex concept in comprehensive detail, while avoiding unnecessary verbosity, this requirement for clarity but also brevity is potentially contradictory. Slight miscalculation of the perceived intellectual capacity of the intended audience may create a risk that the excessive use of what to some becomes incomprehensible jargon, will to them equate with elitism, designed to preclude their participation. In others, the contrary perception of apparently being talked down to, may generate an equally negative effect. My ambiguous personal views in this respect, derive from my experience as a clinician, guiding patients through complex medical dilemmas, where effective communication was essential. I discovered that it was important to vary the level at which the discussion was pitched to where the individual patient was comfortable but in general, the more complex the issues, the greater the need for less obscure language.While this should not be a dilemma in an academic setting, one consequence of my past experiences is a (possibly irrational) sense of trying to appear to be intellectually ostentatious resulting in a strong desire to avoid this. Resolution of this will entail finding a balance between my compulsive tendency to oversimplification in the form of over-elaborate description and my need to get back into the habit of using appropriately formal academic terminology. Fortunately, I feel that I am developing a better sense of realising this degree of equipoise in the visual language of my photography, hence the featured image chosen as the header for this post.

Return to Manchester : Martin Parr

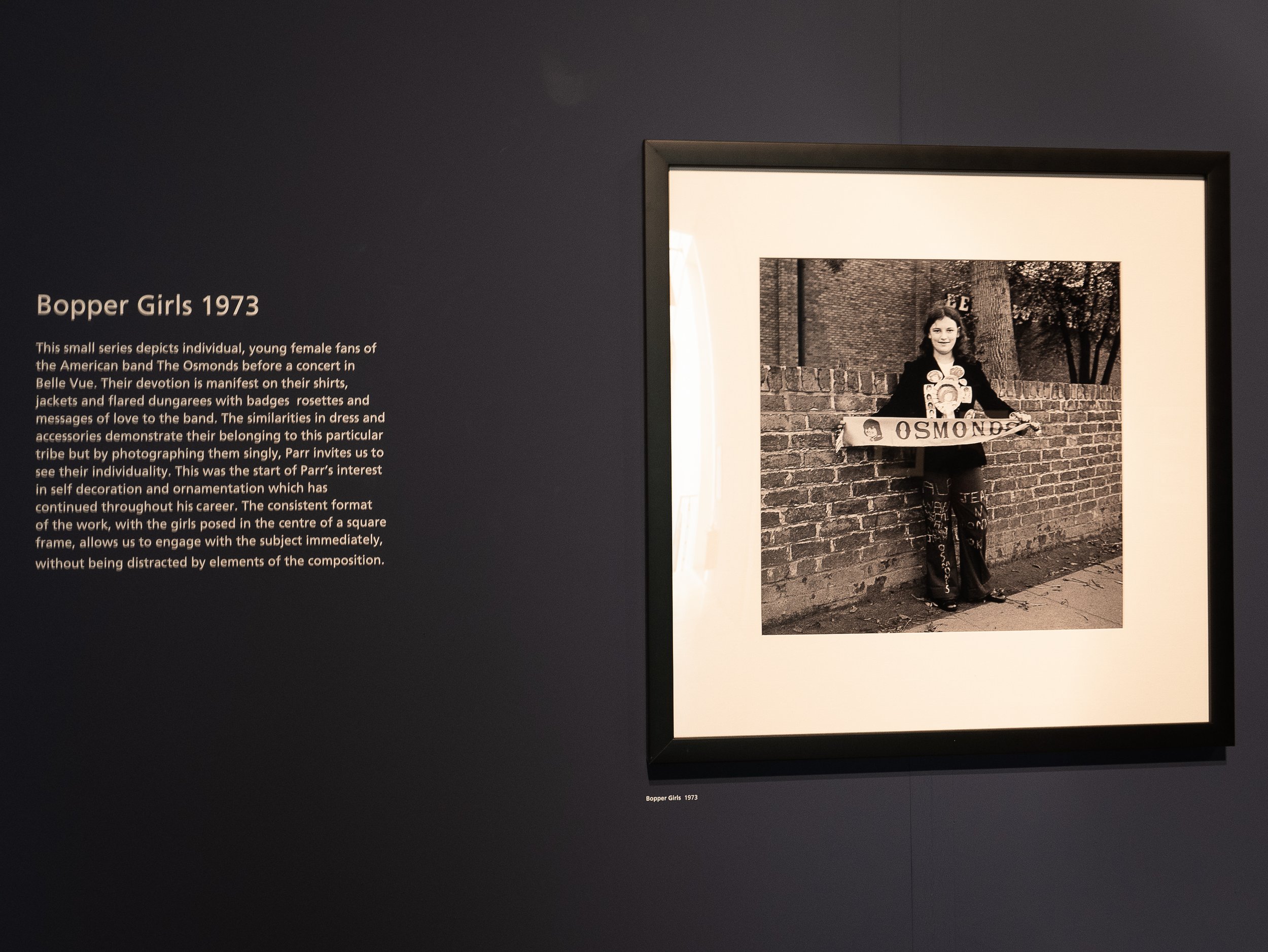

This exhibition currently showing at Manchester Art Gallery focuses on Martin Parr's long term engagement with the people of the city and the surrounding industrial towns of the North West, which form the region of Greater Manchester. From his first student projects in 1970, over a period of nearly fifty years, he has returned regularly and his work now constitutes a substantial documentary record of the changes in the fabric of city's buildings along with its' cultural and social development from an industrial region to modern twenty-first century metropolis.By concentrating on the lives of the inhabitants he has recorded the effects of on one hand, the social deprivation resulting from de-industrialization and on the other, the gentrification of parts of the city, which closely mirrors the changes seen in other major UK cities. The thread which runs through these projects is his ability to capture the warmth and resilience of the people he photographed along the way, especially those from the working class areas. His early black and white photographs are still resonant of the times they covered. His series from the psychiatric hospital in Prestwich are especially poignant and his medium format photographs of girl 'teenyboppers’ manage to capture a sense of the personalities of the teenagers as well as the period detail of their clothing. The layout of the exhibition seamlessly follows his switch to working in colour in the early 1980’s, making the change appear to fit logically with the ways in which that period is now usually remembered (colour in television screens, magazines and newspaper supplements, at that time becoming the norm). The colours recorded in the details of people's everyday lives; shop windows, home decor, clothing, are particularly resonant of the times.

His early black and white photographs are still resonant of the times they covered. His series from the psychiatric hospital in Prestwich are especially poignant and his medium format photographs of girl 'teenyboppers’ manage to capture a sense of the personalities of the teenagers as well as the period detail of their clothing. The layout of the exhibition seamlessly follows his switch to working in colour in the early 1980’s, making the change appear to fit logically with the ways in which that period is now usually remembered (colour in television screens, magazines and newspaper supplements, at that time becoming the norm). The colours recorded in the details of people's everyday lives; shop windows, home decor, clothing, are particularly resonant of the times. More than a few contemporary photographers (including myself) have commented that they find his more recent digital colour images less easy to relate to, which seems difficult to comprehend given that his working methods and subject matter have not significantly changed and the colours and clarity of detail in the images are if anything truer to life. Perhaps now we already know his work so well that there are now simply fewer surprises or the use of digital capture somehow lacks the resonance we felt looking at the earlier work with analogue materials. Alternatively could it be that these images are too close to what we see around us and in the media every day - does familiarity breed contempt? Perhaps if we are still here, we might respond to them more positively in another twenty years time.http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/martin-parr/

More than a few contemporary photographers (including myself) have commented that they find his more recent digital colour images less easy to relate to, which seems difficult to comprehend given that his working methods and subject matter have not significantly changed and the colours and clarity of detail in the images are if anything truer to life. Perhaps now we already know his work so well that there are now simply fewer surprises or the use of digital capture somehow lacks the resonance we felt looking at the earlier work with analogue materials. Alternatively could it be that these images are too close to what we see around us and in the media every day - does familiarity breed contempt? Perhaps if we are still here, we might respond to them more positively in another twenty years time.http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/martin-parr/

Diane Arbus : 'in the beginning'

The Hayward gallery in the South Bank Centre in London is currently showing an exhibition of original monochrome analogue photographs made by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) between 1956 and 1962. Although from the age of eighteen, she had worked in fashion and advertising alongside her husband, the actor and photographer Allan Arbus, she did not embark on the work for which she is now well known, until she was in her early thirties. At that time, while she was studying with Lisette Model, she began to make photographs of people she met in the street in and around the less affluent areas of New York City and Coney Island. These images, best described as her early formative work, were made using 35mm film cameras printed at 6 x 9 inches by Arbus herself and two thirds of them have not been shown previously in the U.K.

The Hayward gallery in the South Bank Centre in London is currently showing an exhibition of original monochrome analogue photographs made by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) between 1956 and 1962. Although from the age of eighteen, she had worked in fashion and advertising alongside her husband, the actor and photographer Allan Arbus, she did not embark on the work for which she is now well known, until she was in her early thirties. At that time, while she was studying with Lisette Model, she began to make photographs of people she met in the street in and around the less affluent areas of New York City and Coney Island. These images, best described as her early formative work, were made using 35mm film cameras printed at 6 x 9 inches by Arbus herself and two thirds of them have not been shown previously in the U.K. As perhaps expected, the quality of the images does not equate with that of her much better known later medium format photographs but the gallery did not permit photography in this exhibition so I have no available examples to show. There was a small area, separate from the main body of the exhibition, showing a folio of ten of her medium format prints (printed at 20 x 20 inches) and the difference in quality was clearly evident. That said, the earlier photographs explored a wider range of subject matter, informal portraits, street photography, people in fairgrounds or at the beach, cinema and theatre audiences and people through restaurant windows. A few images appeared to be screen shots on television sets and there were some found still lives on wet pavements. Several of the prints showed pronounced grain effects and in some (especially the low-light images) the focus was quite soft but this imparted a degree of freshness or rawness to the work which appeared less planned or staged than her photographs from the mid 1960's onwards. This would be an important collection for anyone studying Diane Arbus, demonstrating the early stages of the evolution of her working practice.

As perhaps expected, the quality of the images does not equate with that of her much better known later medium format photographs but the gallery did not permit photography in this exhibition so I have no available examples to show. There was a small area, separate from the main body of the exhibition, showing a folio of ten of her medium format prints (printed at 20 x 20 inches) and the difference in quality was clearly evident. That said, the earlier photographs explored a wider range of subject matter, informal portraits, street photography, people in fairgrounds or at the beach, cinema and theatre audiences and people through restaurant windows. A few images appeared to be screen shots on television sets and there were some found still lives on wet pavements. Several of the prints showed pronounced grain effects and in some (especially the low-light images) the focus was quite soft but this imparted a degree of freshness or rawness to the work which appeared less planned or staged than her photographs from the mid 1960's onwards. This would be an important collection for anyone studying Diane Arbus, demonstrating the early stages of the evolution of her working practice. For my own research, perhaps the most striking aspect of this exhibition was the way in which the work was presented (I made the one photograph shown above before I noticed the small 'No Photography' sign on the plain wall on the right of the image). There were no photographs on the perimeter walls of the space, which were painted in a deep rich matt navy blue (almost black) colour. As shown, the main gallery contained about forty evenly spaced free standing pillars painted in matt white with one photograph only on each long side. The prints were traditionally window mounted in dark metallic pewter like frames and the immediate impressions created by the design were of light airiness and opulently high quality minimalist precision, with a hushed atmosphere indicating genuine reverence for the work being presented.Diane Arbus tragically took her own life in 1971 and I think she would have been pleased with this exhibition but although the gallery has gone to great lengths (and expense) to create an impressive setting for the photographs, I felt to an extent that the design almost overwhelmed the actual images, perhaps reinforcing my impression that this was not her best work. In the information at the gallery entrance, the curators explained that the work had not been arranged in any chronological order and that viewers should feel free to find their own route around the gallery at their own pace. This worked well while the gallery was initially quiet but it filled up quite quickly and I was conscious of people around me moving from pillar to pillar in different directions at different speeds to the extent that I felt under pressure to move on, to avoid holding them up. Although many were individually fascinating, the disparate selection of images were placed surprisingly randomly with no obvious attempt to formally sequence them. This could of course have been an attempt to subliminally re-create the feel of the circumstances in which they were created but overall it felt more like a triumph of style over substance.https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/diane-arbus-beginninghttps://www.biography.com/people/diane-arbus-9187461

For my own research, perhaps the most striking aspect of this exhibition was the way in which the work was presented (I made the one photograph shown above before I noticed the small 'No Photography' sign on the plain wall on the right of the image). There were no photographs on the perimeter walls of the space, which were painted in a deep rich matt navy blue (almost black) colour. As shown, the main gallery contained about forty evenly spaced free standing pillars painted in matt white with one photograph only on each long side. The prints were traditionally window mounted in dark metallic pewter like frames and the immediate impressions created by the design were of light airiness and opulently high quality minimalist precision, with a hushed atmosphere indicating genuine reverence for the work being presented.Diane Arbus tragically took her own life in 1971 and I think she would have been pleased with this exhibition but although the gallery has gone to great lengths (and expense) to create an impressive setting for the photographs, I felt to an extent that the design almost overwhelmed the actual images, perhaps reinforcing my impression that this was not her best work. In the information at the gallery entrance, the curators explained that the work had not been arranged in any chronological order and that viewers should feel free to find their own route around the gallery at their own pace. This worked well while the gallery was initially quiet but it filled up quite quickly and I was conscious of people around me moving from pillar to pillar in different directions at different speeds to the extent that I felt under pressure to move on, to avoid holding them up. Although many were individually fascinating, the disparate selection of images were placed surprisingly randomly with no obvious attempt to formally sequence them. This could of course have been an attempt to subliminally re-create the feel of the circumstances in which they were created but overall it felt more like a triumph of style over substance.https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/diane-arbus-beginninghttps://www.biography.com/people/diane-arbus-9187461

Anders Pleass : Making and taking pictures - a selective relation between painting and photography.

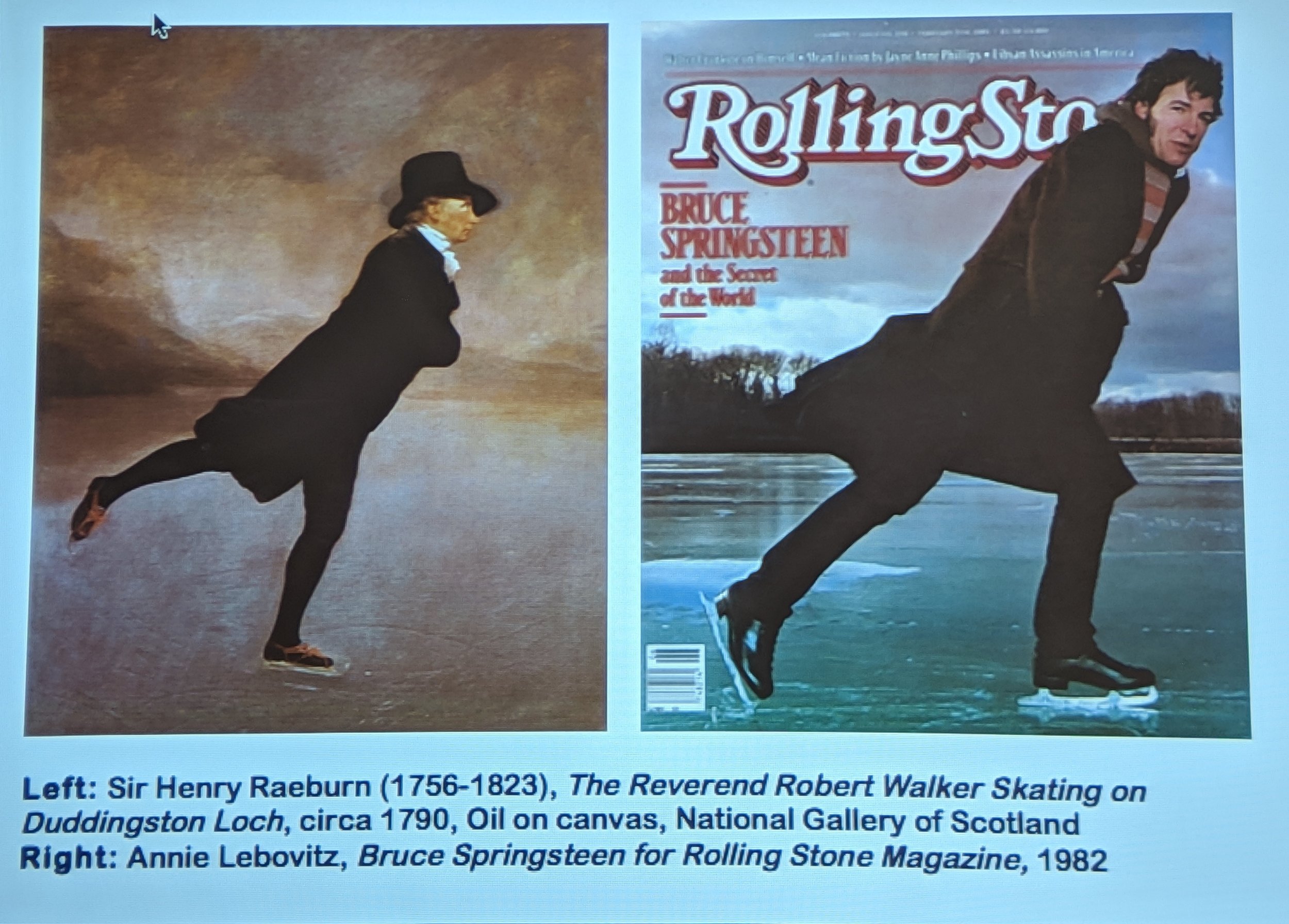

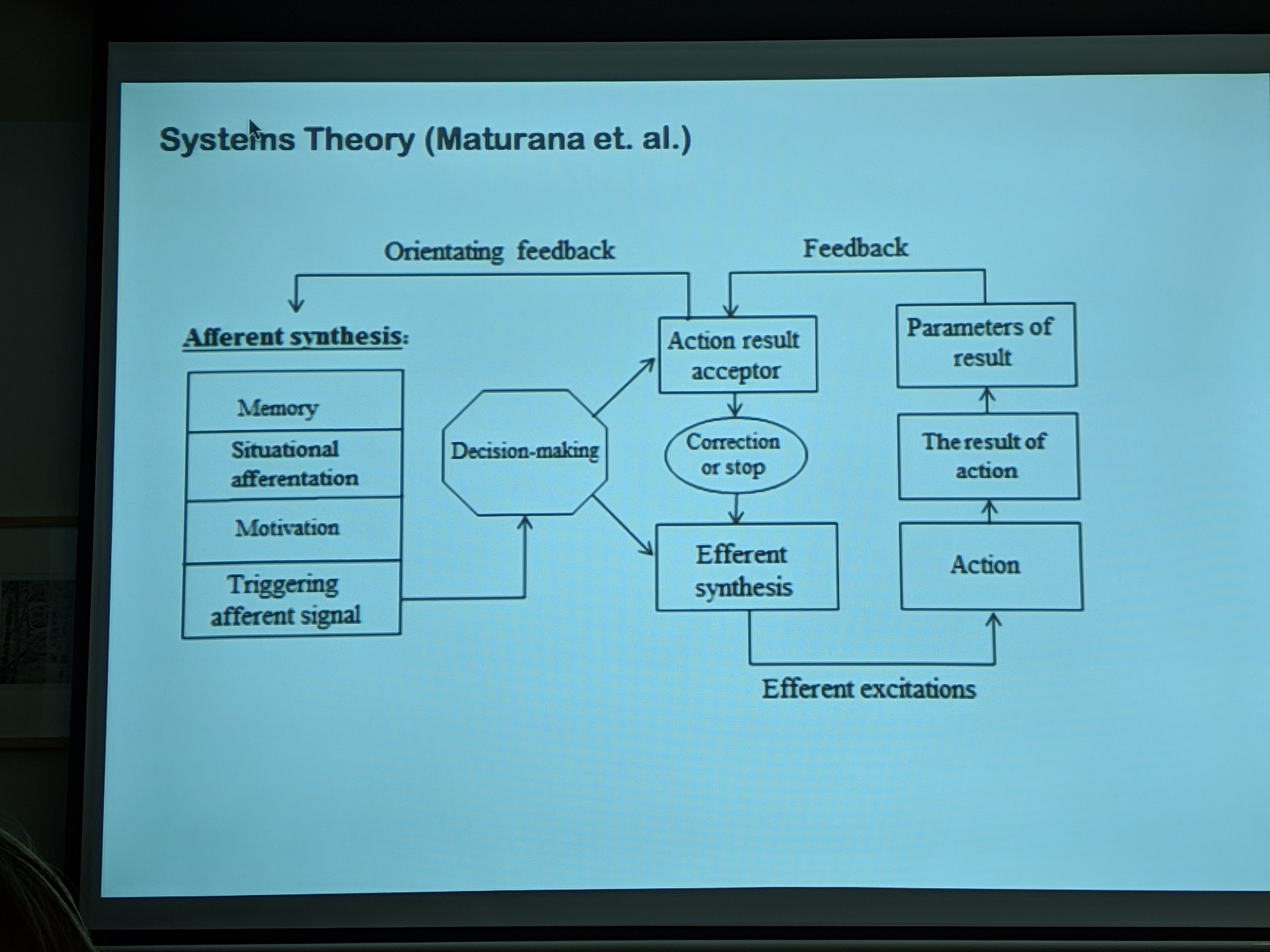

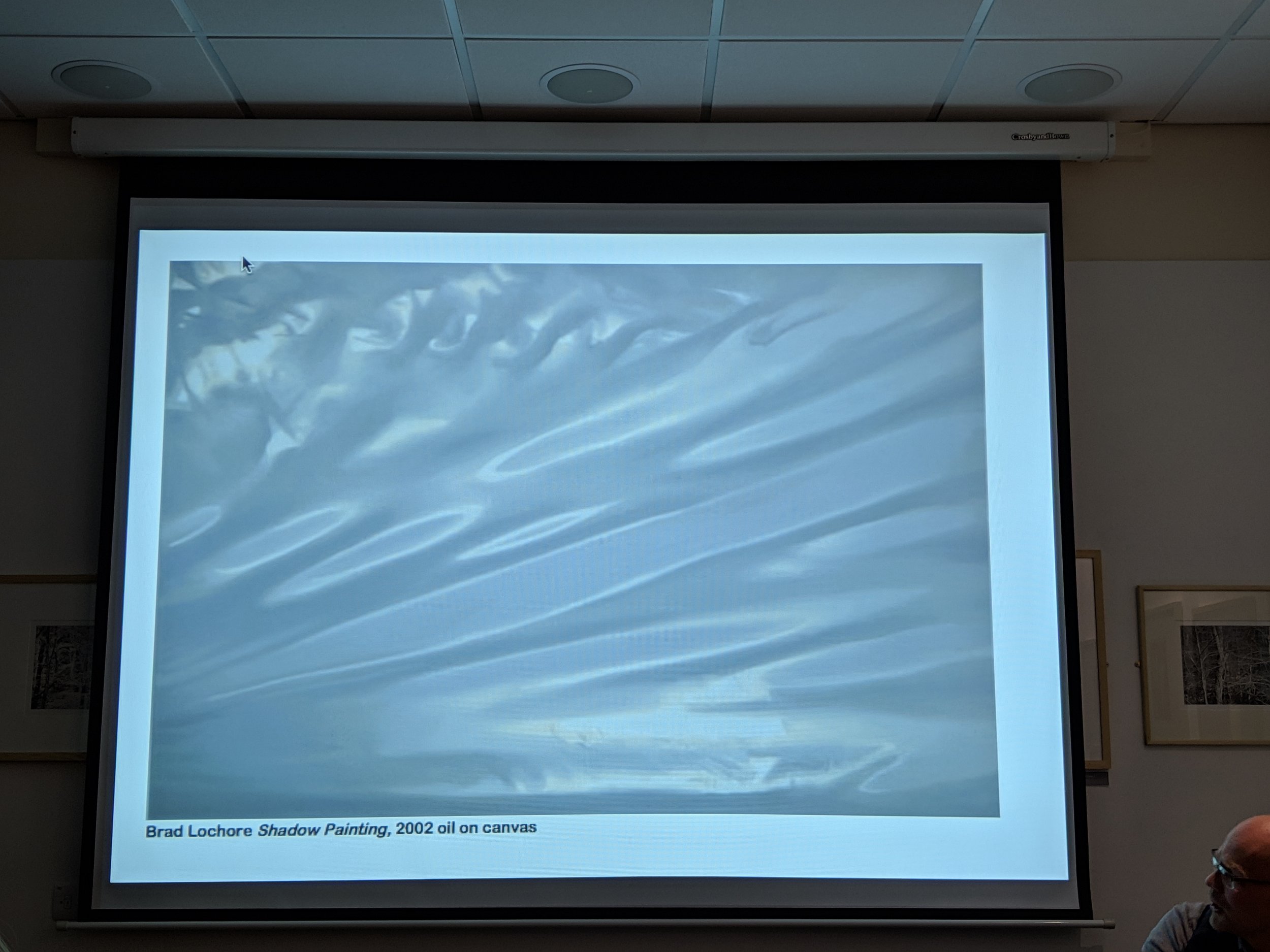

This gallery lecture was delivered by Anders Pleass, at Oriel Colwyn on 28th February, in support of their current exhibition of John Hedley's images of rock formations and trees, which are produced using a combination of digital photography with traditional intaglio printmaking. In a wide-ranging presentation, he described his personal journey from an undergraduate in environmental biology to studying fine art and his attempts to take the lessons from his scientific background into painting, incorporating these in a creative model in developing his 'post-painterly abstraction' techniques for making images. As the slide from his talk used as a featured image for this post shows, he has a detailed knowledge of art history and an ability to recognise when artists (and photographers) reference work from the past when researching their ideas for projects. He described in detail his own research into art theory, significantly influenced by the writings of modernist and post-modernist thinkers, notably the visual art critic Clement Greenberg, the philosopher A. J. Ayer and the novelist and art theorist André Malraux. The artists whose work influenced his practice included Morris Lewis, Ian Davenport, Calum Innes and Bernard Frize but in addition to post-painterly abstraction he studied Systems Theory (Humberto Maturana), Chaos Theory (Edward Norton Lorenz) and comparative embryology, Emergence Theory and more general interests including theatre (especially Shakespeare and the Riddle of the Sphinx from Oedipus Rex). The artist he worked most closely with was Brad Lochore, some of whose large paintings of shadows (which I was previously unaware of) are superficially very similar to a series of photographs I have been making over the last two years. Pleass assisted in the making of these paintings for several years as a painter technician and explained that they were based on photographs which were transcribed onto canvas, section by section using a technique which he described as being almost like 'painting with numbers'.

The artist he worked most closely with was Brad Lochore, some of whose large paintings of shadows (which I was previously unaware of) are superficially very similar to a series of photographs I have been making over the last two years. Pleass assisted in the making of these paintings for several years as a painter technician and explained that they were based on photographs which were transcribed onto canvas, section by section using a technique which he described as being almost like 'painting with numbers'. Although his work with Lochore provided an income, he had no artistic input (Lochore never involved him in the creative process or even discussed the images with him) and he went on to talk candidly about the tribulations of trying to establish his own career as an artist and his subsequent transition to his present vocation as a freelance curator. He first met John Hedley in 2014 when they were both teaching in the Arts Department at Coleg Llandrillo and credits Hedley with introducing him to the educational concepts of visual literacy and hermeneutics. He described the working process used by Hedley as 'primordial image formation', images which appear as metamorphoses evolving from the natural world. The two groups of intaglio prints in this exhibition are firstly monochrome images trees in a woodland and secondly the surfaces of rock formations (in Anglesey and Crete). Pleass feels that the real subject of them is 'time', as in ideas of time moving slowly, the timescales of their references to art history and geological time. He also commented on the similarities in some of them to satellite images and aerial photography.My interest in the work and the reason for going to this lecture, was in the process used as an example of a hybrid technique which combining photography with traditional printmaking. While I am still exploring several potential areas for my research project, it will include studying an aspect of the interface between analogue and digital technology (hence the title of my blog). I also have a shared interest in his subject matter having worked with textures in, rock surfaces, tree bark and sand dunes as well as my photographs of shadows, reflected light and paintwork. The additional bonuses of attending this talk were the depth of the contextual background information covered by Pleass and learning about several artists whose work I should now consider. John Hedley is giving his own talk about his working methods in the next few weeks and I hope to be able to get there.

Although his work with Lochore provided an income, he had no artistic input (Lochore never involved him in the creative process or even discussed the images with him) and he went on to talk candidly about the tribulations of trying to establish his own career as an artist and his subsequent transition to his present vocation as a freelance curator. He first met John Hedley in 2014 when they were both teaching in the Arts Department at Coleg Llandrillo and credits Hedley with introducing him to the educational concepts of visual literacy and hermeneutics. He described the working process used by Hedley as 'primordial image formation', images which appear as metamorphoses evolving from the natural world. The two groups of intaglio prints in this exhibition are firstly monochrome images trees in a woodland and secondly the surfaces of rock formations (in Anglesey and Crete). Pleass feels that the real subject of them is 'time', as in ideas of time moving slowly, the timescales of their references to art history and geological time. He also commented on the similarities in some of them to satellite images and aerial photography.My interest in the work and the reason for going to this lecture, was in the process used as an example of a hybrid technique which combining photography with traditional printmaking. While I am still exploring several potential areas for my research project, it will include studying an aspect of the interface between analogue and digital technology (hence the title of my blog). I also have a shared interest in his subject matter having worked with textures in, rock surfaces, tree bark and sand dunes as well as my photographs of shadows, reflected light and paintwork. The additional bonuses of attending this talk were the depth of the contextual background information covered by Pleass and learning about several artists whose work I should now consider. John Hedley is giving his own talk about his working methods in the next few weeks and I hope to be able to get there.

‘A Summer of Discovery in Wales: Aerial Archaeology and the Remarkable Heatwave of 2018’

January 29th 2019I went to this lecture, given by Dr Toby Driver on behalf of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales at Pontio in Bangor last night. He described the use of aerial photography during the surprisingly hot, dry period in late June and July last year when the cropmarks in the fields throughout Wales, revealed many sites of archaeological interest which have been buried under the ground for hundreds and in some cases thousands of years. These images of the outlines of sites which cannot normally be seen on the surface, included several completely new discoveries in areas previously unknown to contain any historical artefacts. They also revealed many of the recorded sites in unusually clear detail and revealed a number of new areas of potential interest in the land adjacent to them.The lecturer explained that the mechanism by which these cropmarks appear depends on the differential growth, ripening and drying out of the plants due to the amount of water held in the underlying soil. Where the layer of soil is deeper, for example where there have been ditches around fortified buildings or pits for waste, more water is retained and the growth remains lush and green, drying out and yellowing more slowly than the surrounding areas. Here the soil is shallow, over paved areas, roads or the footings of buildings, the crops run out of water and dry out more quickly. The unusual feature of last summer was the length of the period without any rainfall - the cropmarks normally disappear quickly after any rainfall and are also destroyed when they are harvested by the farmers (who need to do this before they spoil) or grazed by livestock. The drought provided the researchers with a three week interval allowing them 35 hours of flying time in which they made a total of 5700 digital exposures. They are still in the process of reviewing and analysing these photographs which can also involve enhancing the information from them in Photoshop, using tonal separation tools in the colour channels (concentrating on shades of greens and yellows) to produce remarkably detailed monochrome images. The cultures which created the structures and building outlines seen in the images range from prehistoric tribes, through the Celtic people of the Bronze and Iron Ages, the Roman Occupations and Mediaeval populations right up to the early part of the twentieth century. The structures seen include settlements and hut circles, burial mounds and iron age barrows, ditches, field systems and enclosures, Roman roads, forts, marching camps, villas and bath houses, mediaeval churches, monasteries and graveyards and training camps dating from the first world war (e.g. on the Kinmel Estate near Bodelwyddan). The researchers are particularly interested in the relatively poorly documented routes used by the Roman armies in subjugating the Silurian tribes in South Wales and the Ordovices and Deceangli in North Wales in the period between 47AD and the end of the first century and believe they have identified potential sites for several previously undocumented marching camps and new sections of the Roman road network. While these will need to confirmed by groundwork, geophysics and LIDAR imaging this appears to be a good example of the use of this highly specialised application of photography as a tool for ethnographic research.www.rcahmw.gov.uk (Cymraeg = www.cbhc.gov.uk)www.coflein.gov.ukThe images used to illustrate this post were taken by Dr Toby Driver and were retrieved from the website of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales who hold the Crown Copyright for them.

The cultures which created the structures and building outlines seen in the images range from prehistoric tribes, through the Celtic people of the Bronze and Iron Ages, the Roman Occupations and Mediaeval populations right up to the early part of the twentieth century. The structures seen include settlements and hut circles, burial mounds and iron age barrows, ditches, field systems and enclosures, Roman roads, forts, marching camps, villas and bath houses, mediaeval churches, monasteries and graveyards and training camps dating from the first world war (e.g. on the Kinmel Estate near Bodelwyddan). The researchers are particularly interested in the relatively poorly documented routes used by the Roman armies in subjugating the Silurian tribes in South Wales and the Ordovices and Deceangli in North Wales in the period between 47AD and the end of the first century and believe they have identified potential sites for several previously undocumented marching camps and new sections of the Roman road network. While these will need to confirmed by groundwork, geophysics and LIDAR imaging this appears to be a good example of the use of this highly specialised application of photography as a tool for ethnographic research.www.rcahmw.gov.uk (Cymraeg = www.cbhc.gov.uk)www.coflein.gov.ukThe images used to illustrate this post were taken by Dr Toby Driver and were retrieved from the website of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales who hold the Crown Copyright for them.

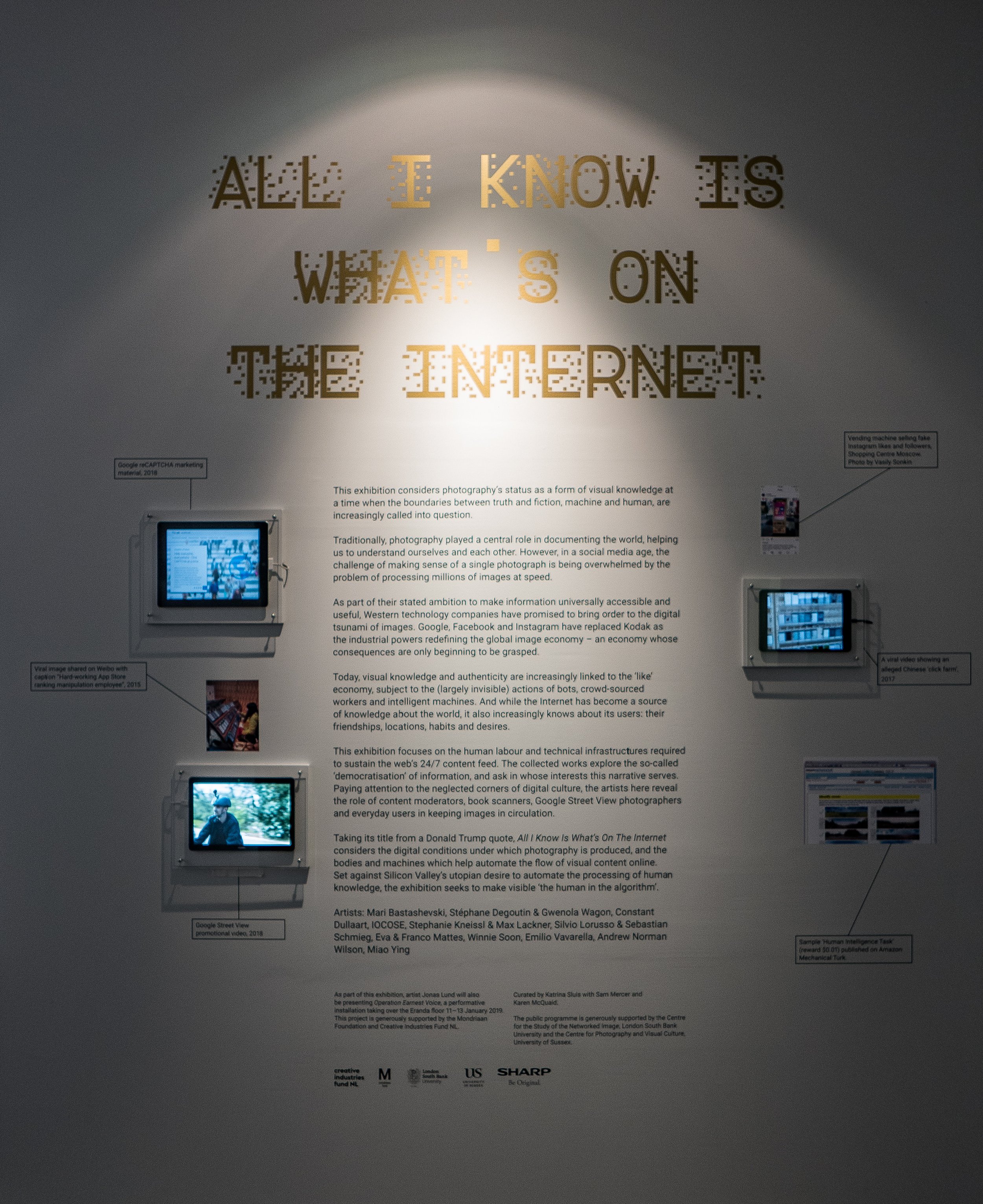

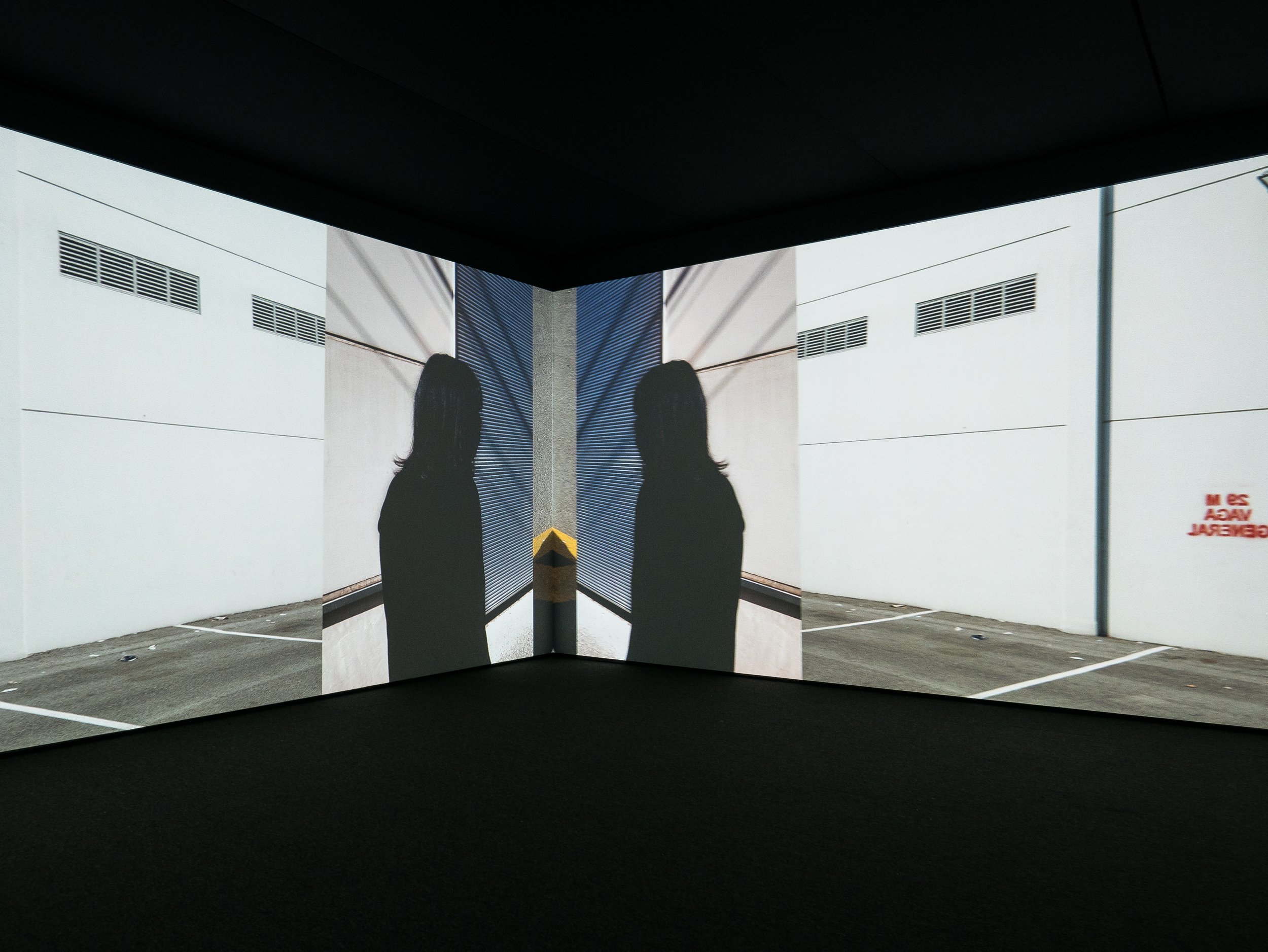

All I know is what's on the internet

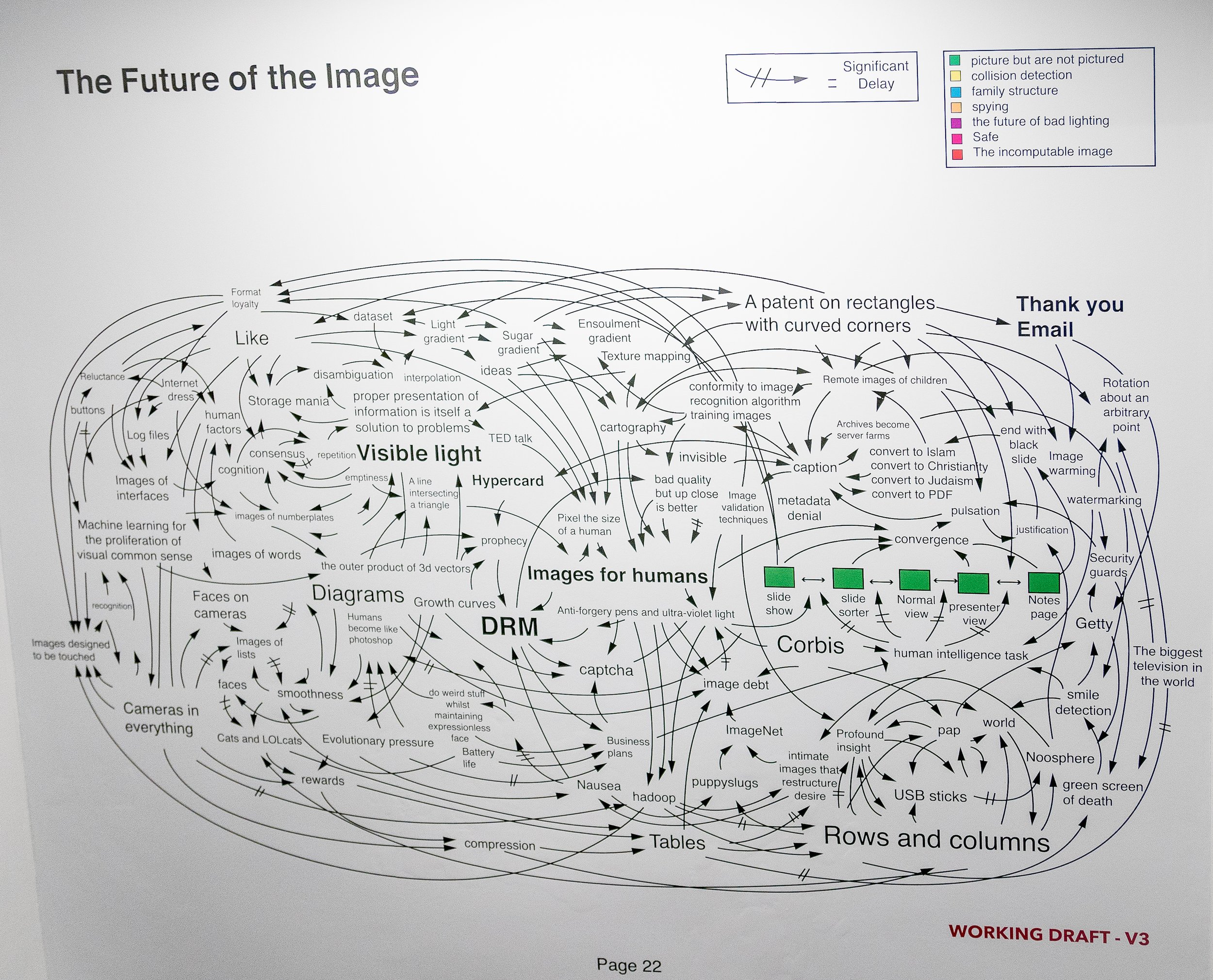

This exhibition currently showing at the Photographers' Gallery in London is a study of a group of artists examining several aspects of the effects of digital imaging and online media on the ways in which photography is used in contemporary cultures. The title is a quote from one of Donald Trump's press interviews during the 2016 US presidential election campaign which perhaps reflects the less than positive effects some of the contributors have uncovered in their research. Although the impression is often given that everything that happens on the internet is fully automated, the exhibition looks at the huge workforce required to support the infrastructure of the involved technology companies, service providers, search engines and social media platforms, including among others programmers, online support teams, 'clickworkers', content moderators, people employed to copy books for online publication and google street view camera operators. The issues of manipulation of cultural tastes (the 'like' economy and false social media accounts) and of unequal access to online content in different parts of the world are also explored. This was not a typical photography exhibition in the sense of the images being visually or aesthetically stimulating but it was certainly thought provoking and there was a lot to take in. The image which left the strongest impression was a mind map produced for the Photographer's Gallery by Mathew Fuller and Olgia Goriunova, exploring the future role of photography which was described as a deliberately 'incomprehensible diagram' based on a Powerpoint slide from a presentation by General Stanley A. McChrystal who was quoted as saying "when we understand that slide we will have won the war"

This was not a typical photography exhibition in the sense of the images being visually or aesthetically stimulating but it was certainly thought provoking and there was a lot to take in. The image which left the strongest impression was a mind map produced for the Photographer's Gallery by Mathew Fuller and Olgia Goriunova, exploring the future role of photography which was described as a deliberately 'incomprehensible diagram' based on a Powerpoint slide from a presentation by General Stanley A. McChrystal who was quoted as saying "when we understand that slide we will have won the war" There can be no doubt that the role of still photography is changing rapidly but where it will end up in the future is anybody's guess. I left this exhibition feeling I need to engage more actively with the online world if I am ever going to make any sense of it. Perhaps the exercise of writing this blog will prove to be a good starting point.https://thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internethttps://thehill.com/blogs/ballot-box/presidential-races/272824-trump-all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internetPhotographs of the installation used were taken at the exhibition by the blog author.Update 17 Feb 2019 Have recently seen the film 'WhiskyTangoFoxtrot' which was based on the memoir of the American journalist Kim Barker. A copy of the original US Army diagram on which the above image is based appears in a scene set in an army intelligence briefing room.https://www.comingsoon.net/movie/whiskey-tango-foxtrot-2016#/slide/1

There can be no doubt that the role of still photography is changing rapidly but where it will end up in the future is anybody's guess. I left this exhibition feeling I need to engage more actively with the online world if I am ever going to make any sense of it. Perhaps the exercise of writing this blog will prove to be a good starting point.https://thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internethttps://thehill.com/blogs/ballot-box/presidential-races/272824-trump-all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internetPhotographs of the installation used were taken at the exhibition by the blog author.Update 17 Feb 2019 Have recently seen the film 'WhiskyTangoFoxtrot' which was based on the memoir of the American journalist Kim Barker. A copy of the original US Army diagram on which the above image is based appears in a scene set in an army intelligence briefing room.https://www.comingsoon.net/movie/whiskey-tango-foxtrot-2016#/slide/1

The Photographers' Gallery, London

While in London last month I also visited the Photographers' Gallery where the two current exhibitions on show are 'Roman Vishniac Rediscovered' (in collaboration with the Jewish Museum of London) and 'All I Know is What's on the Internet' (a quote from Donald Trump). I will consider the second of these in a separate blog.

While in London last month I also visited the Photographers' Gallery where the two current exhibitions on show are 'Roman Vishniac Rediscovered' (in collaboration with the Jewish Museum of London) and 'All I Know is What's on the Internet' (a quote from Donald Trump). I will consider the second of these in a separate blog. The larger exhibition, on Levels 4 and 5 of the gallery is an extensive retrospective of the Russian born American photographer Roman Vishniac (1897-1990). Vishniac had moved from Moscow to Berlin to escape the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1920 and his best known body of work is a large social documentary portrait of the Jewish population of Eastern Europe, mainly Berlin and Warsaw in the inter-war years, coinciding with the evolution of modernism and the rise of fascism with the resultant persecution of these communities. It is a unique document of the dramatic changes in these societies from a atmosphere open to artistic expression and social multiculturalism to the sectarianism and oppression of the Nazi regime and the populations decimated by their policies.The layout of most of the exhibition is a traditional wall mounted chronological sequence of very fine vintage (and some newly re-printed) monochrome prints, including studio and candid portraits as well as street photography and images of agricultural workers. On escaping from Germany in the mid-1930's, he moved to the USA and quickly established a successful commercial portrait studio. His other interest was the photography of microscopic life forms and his pioneering work in colour photomicrography led to an academic career and professorships in biology and fine art photography in several American universities - a selection of these images were presented in a separate room from the main exhibition as a projected slide show along with several of his publications displayed in glass cases.The quality of his work is very impressive and the social documentary work is genuinely moving but aside from this and his imaginative use of atmospheric shadows, the relevance to my own current practice is of limited relevance.www.thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/roman-vishniac-rediscovered

The larger exhibition, on Levels 4 and 5 of the gallery is an extensive retrospective of the Russian born American photographer Roman Vishniac (1897-1990). Vishniac had moved from Moscow to Berlin to escape the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1920 and his best known body of work is a large social documentary portrait of the Jewish population of Eastern Europe, mainly Berlin and Warsaw in the inter-war years, coinciding with the evolution of modernism and the rise of fascism with the resultant persecution of these communities. It is a unique document of the dramatic changes in these societies from a atmosphere open to artistic expression and social multiculturalism to the sectarianism and oppression of the Nazi regime and the populations decimated by their policies.The layout of most of the exhibition is a traditional wall mounted chronological sequence of very fine vintage (and some newly re-printed) monochrome prints, including studio and candid portraits as well as street photography and images of agricultural workers. On escaping from Germany in the mid-1930's, he moved to the USA and quickly established a successful commercial portrait studio. His other interest was the photography of microscopic life forms and his pioneering work in colour photomicrography led to an academic career and professorships in biology and fine art photography in several American universities - a selection of these images were presented in a separate room from the main exhibition as a projected slide show along with several of his publications displayed in glass cases.The quality of his work is very impressive and the social documentary work is genuinely moving but aside from this and his imaginative use of atmospheric shadows, the relevance to my own current practice is of limited relevance.www.thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/roman-vishniac-rediscovered

A Very Very Very Dark Matter

My son bought us tickets for this new play at the Bridge Theatre on London’s South Bank, because he knew that I had enjoyed the work of the playwright Martin McDonagh (who wrote the film screenplays for ‘In Bruges’ and ‘Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri’). On that basis but knowing little else about it in advance, we expected a story with dark humour, irreverence, subversion and unpredictable plot twists – and it had all of these, at least in parts. The first and third acts starred Johnetta Eulua’Mae Ackles as a Congolese dwarf imprisoned in a locked cage, suspended from the ceiling of an attic in mid-19th century Copenhagen, in which she was forced to write stories for Hans Christian Andersen (played as a pompous overbearing buffoon by Jim Broadbent), who then published them in his own name and who had also cut off her right foot to stop her escaping. The story was explained by an offstage narrator, voiced by Tom Waits (presumably pre-recorded) and centred on the contradictory and ambiguous aspects of the personality of the prolific and highly successful writer of children’s stories, as well as some less well known novels and travelogues. Other issues explored included disability/deformity, racism, colonialism, genocide (by the Belgian Army in the Congo), authorship/plagiarism, repressed but ambiguous sexuality, obsessive but unrequited passion, time-travelling ghosts and a haunted accordion with a concealed machine gun.While this all sounds like a surrealist fantasy (which is what I think it was), it is evident that the author has undertaken a considerable amount of research in preparation for writing the story. Several biographers have referred to Andersen’s unusual personality, based on contemporary accounts and from his own diaries. He had a difficult childhood in which he was abused by strictly religious adoptive parents. He was celibate because of his religious beliefs and never married but became intensely infatuated at various times in his life with individuals of both sexes, none of whom reciprocated his feelings (Lepage, 2006). The second act, set around Charles Dickens’ dining room table, was based on a visit by Andersen to the author’s home in which he bored and irritated Dickens and his family by outstaying his welcome by several weeks. He died in unusual circumstances after falling out of his bed and a small skeleton with the right foot missing, was found in his attic after his death.Press reviews of the play have been at best mixed, with several commenting that the plot was overcomplicated, disjointed, deliberately shocking to the point of being over-sensationalised and some found the humour gratuitously offensive (Online reviews, 2018). It seemed as if the play had been written in a hurry or possibly originally envisaged as a film and I thought the story did at times stray close to the line between an effective piece of ‘theatre of the absurd’ and flippant or frivolous silliness. For me however this was offset greatly by the dark shadowy lighting and the atmospheric set design of the attic by Anna Fleischle, with Gothic arched ceilings, scattered dolls and children’s toys and hanging puppets. The effect of this was to create a uniquely surreal visual experience and although the script could have been more cohesive, it was a very different and enjoyable theatrical spectacle, a dark stranger than fiction fairytale.ReferencesLepage R, 2006. ‘The perverse side of Hans Christian Andersen’, Guardian newspaper article Accessed on 30/11/2016 at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/jan/18/theatre.classicsOnline reviews, 2018. Accessed on 30/11/2018 at: https://www.whatsonstage.com/london-theatre/news/very-dark-matter-review-round-up-critics-bridge_47880.htmlImagesFeatured banner image copied from the Bridge Theatre website, Accessed on 5/12/2018 at: https://bridgetheatre.co.uk/whats-on/a-very-very-very-dark-matterSet design photograph copied from the Jewish Chronicle website, Accessed on 5/12/2018 at: https://www.thejc.com/culture/theatre/theatre-review-a-very-very-very-dark-matter-1.472020

The effect of this was to create a uniquely surreal visual experience and although the script could have been more cohesive, it was a very different and enjoyable theatrical spectacle, a dark stranger than fiction fairytale.ReferencesLepage R, 2006. ‘The perverse side of Hans Christian Andersen’, Guardian newspaper article Accessed on 30/11/2016 at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/jan/18/theatre.classicsOnline reviews, 2018. Accessed on 30/11/2018 at: https://www.whatsonstage.com/london-theatre/news/very-dark-matter-review-round-up-critics-bridge_47880.htmlImagesFeatured banner image copied from the Bridge Theatre website, Accessed on 5/12/2018 at: https://bridgetheatre.co.uk/whats-on/a-very-very-very-dark-matterSet design photograph copied from the Jewish Chronicle website, Accessed on 5/12/2018 at: https://www.thejc.com/culture/theatre/theatre-review-a-very-very-very-dark-matter-1.472020

Viviane Sassen