The presenter of the Annual Lecture of the Scottish Society for the History of Photography (SSHoP) at the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh on 15th November 2019, was the contemporary fine art photographer Garry Fabian Miller. His presentation lasted just over one hour in which he described his career to date in detail including his family background, influences, a brief description of his early social documentary and landscape work, the thinking behind his switch in 1984 to camera-less photography, his current working practice and his collaborations with other artists, writers, poets and musicians.Born in 1957 to parents who ran (and lived in) a long established family studio photography business in Bristol, he was immersed in the atmosphere of the darkroom from early childhood. As a teenager his ambition was to become a 'serious' photographer, at a time when this effectively equated with social documentary photography. His first significant project as a teenager, influenced by the work of Paul Strand in the Outer Hebrides, involved at the age of sixteen, spending the summer of 1973 in the Shetland Islands, living with and documenting the lives of crofters and their families. Several of these images featured in the lecture and this experience of the cycles of rural life in remote wild places, has been a major influence on his life and work since then.A singular feature of his practice has been his use of Cibachrome paper and the dedicated chemistry required to process it, to produce all of his images since 1976. This dye destruction paper, designed as a reversal process for producing direct positive prints from colour transparencies, was known for its distinctively vivid but true to life colour palette, strikingly high gloss almost metallic surface finish and exceptional archival stability. Fabian Miller found that with long enough exposures, he was able to use this paper instead of film in a 10x8 inch large format camera, to photograph seascapes of the Severn Estuary from an attic window in his home. This resulted in 'Sections of England: The Sea Horizon' his first major work, which was first shown in 1977 in the Serpentine Gallery in London and formed the basis of his first solo exhibition in the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol in 1979.He moved to live in a farm in Lincolnshire in 1980 and having developed an interest in Land Art, he transformed a barn into a small gallery, where he met and showed the work of among others Hamish Fulton, Andy Goldsworthy, David Nash, Marie Yates and Roger Ackling. In 1984 he started experimenting with the use of semi-translucent natural materials, grasses, leaves, seed heads and flower petals, placed in the negative carrier of his enlarger and exposed onto Cibachrome paper to make photographs direct from life. By the following year he had decided at the age of 25, that he no longer needed a camera. He made several seasonally based series of images, documenting the sequential changes in the colour of leaves as the chlorophyl levels changed over a period of weeks and several of these are now in the permanent collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.In 1989 he moved with his family to Dartmoor, designed and built a studio with his darkroom at the bottom of their large garden, where he estimates he has spent at least fifty per cent of his waking hours ever since. In around 1992 he virtually stopped using plant materials having developed a technique for projecting beams of light, filtered through glass vessels containing coloured oils and liquids, directly onto photosensitive paper, with only small pieces of card placed in the light path to produce the geometric shapes in his photographs. His work has become progressively more abstract and since 2017, he has experimented with using additional small light sources, for example burning matches, to produce localised bright highlights mimicking the appearance of flames. His daily routine also involves walking , either in the early morning or the evening, taking inspiration in the special auras of light in the skies and the colours this produces in the blossoms of the vegetation, along with the atmosphere of the ancient archeological sites and burial cairns on the surrounding moorland, which he tries to represent in his work. Although most of his work has been made in his own darkroom, he has made some images on visits to the islands of Tiree, off the West coast of Scotland, Skellig Michael and Inis Meain (one of the Aran Islands), both off the West coast of Ireland. He described Inis Meain as one of the last bastions of purity in Ireland, a view shared by the artist Sean Scully, who made one of his few books of photographs on the island. While Fabian Miller always works alone in his darkroom, when it comes to distributing his work he has collaborated extensively with other artists including writers, poets, musicians, potters, weavers and curators. One of his most important collaborations over the years has been with Martin Barnes, the curator of Photography at the V&A Museum, who has aquired his work for their collection, wrote an introduction to one of his books, curated his 2005 exhibition at the V&A and included his work in the major retrospective exhibition of camera-less photography, 'Shadow Catchers' also at the V&A in 2011. Several other authors have also contributed to sections in his books, including Marina Warner, Nigel Warburton and Adam Nicolson (The Colour of Time, 2010) and the author and ceramicist Edmund de Waal with the poet Alice Oswald (Blaze, 2019). Alice Oswald has also collaborated in live performances of his work along with her poetry as has the cellist and composer Oliver Coates. Since 2013, Fabian Miller has also worked with the weavers in the Dovecot Studio in Edinburgh, making gun tufted rugs (some of which have been acquired by the Standard Life Aberdeen Investment Bank for the foyer of their Edinburgh Head Office - see photograph above) and in 2017 a tapestry, based on the colours and shapes in his photographs. Probably his most important collaboration over the last ten years has been with John Bodkin a master of digital printing who has helped in the challenging process of colour correcting high resolution scans of Fabian Miller's Cibachrome prints, while trying to maintain as closely as possible the subtleties of their original appearance and surface. This allows them to be re-printed to archival standards as 'C'prints using the Lambda Lightjet printing system, for exhibition at a much larger scale. Some of these prints were recently exhibited at the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh who have also worked closely with Fabian Miller for many years (see previous post from 16 Dec 2019).Moving into the third decade of the 21st century, it is relatively unusual to find an internationally acclaimed photographer whose primary method of creating images is so completely dependent on a traditional wet darkroom process. This is all the more surprising on discovering that no Cibachrome papers have been manufactured since 2012. Cibachrome papers are relatively stable if correctly stored (in a freezer) and Fabian Miller had the foresight to stock up when the last batch was produced. This supply is running out and he is down to his last one hundred sheets. There may be a few individuals around the world who still have small stocks in storage but they are unlikely to become available and their archival status will be unpredictable. The Cibachrome process chemistry is if anything more difficult to store and although there are possible work arounds using monochrome developers and RA4 process bleach/fix, he has decided that when he completes his current project using his remaining stock, he will close his darkroom forever. A very well written account of the saga of the demise of Cibachrome/Ilfochrome is available online (Vincent 2018).Under the circumstances, Fabian Miller seems remarkably optimistic about the future. He has a large library of work already made and now has access to the skills required to work with this digitally. He stopped selling his Cibachrome originals some time ago to retain them for future projects and now only sells his work as Lambda Lightjet 'C'prints. Although his work has can appear very precise and controlled, his almost poetic relationship with the elemental forces which shape his connection to the land are still very apparent. He discovered very recently that the building in Bristol in which he had been brought up, was at one time owned by the publisher Joseph Cottle. In one of their well documented walking tours in the 1790's, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, stayed for several days with Cottle in Bristol, before crossing the Severn by ferry to travel up the Wye Valley to Tintern. It transpires that Dorothy Wordsworth slept in the bedroom, which in later years became the darkrooom in which he still remembers playing as a child, while his parents were printing their work. He is currently trying to work out if there is a way of using this in the generation of his next project.The importance of the darkroom and its role in the history of the photography which so dramatically transformed our interactions with the rest of the world, can perhaps only be fully appreciated by those who have experienced working in one. In an attempt to address this, Historic England spent several days with Fabian Miller in 2016, documenting his working process. He has also made arrangements with the V&A Museum that when he does close his darkroom, it will be dismantled and installed in their Photography section as a new exhibit for visitors to experience. His archive of darkroom notebooks will also be acquired by the museum to be made available to future researchers.In discussion following the lecture, he was asked if his experience of the demise of Cibachrome felt like coming to the end of a prolonged terminal illness. While agreeing that the end of Cibachrome was sad, he feels that the potential of digital photography is exciting and that it is probably still in its infancy, with much still to be explored. He feels that it is important that people understand that the invention of chemical photography was a seminal moment in world history and is encouraged by the fact that there are still people who are trying to keep it alive. He has been thinking for some time about the early experiments of Fox Talbot and his correspondence with John Herschel, wondering if there is any scope for further research into this source material for clues as to developing other new processes. Examples of Fabian Miller's work and links to interviews with him are available at the websites of the V&A Museum, the Ingleby Gallery and on his own site, at www.garryfabianmiller.com. Barnes M. and Fabian Miller G. (2005) 'Illumine'. Merell Publishing London.Barnes M. (2012) 'Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography'. Merell Publishing London.Fabian Miller G. (2010) 'The Colour of Time'. Black Dog Publishing, London.Fabian Miller G. (2019) 'Blaze" Ingleby, Edinburgh.Scully S (2007) 'The Walls of Aran' Thames and Hudson, London.https://www.inglebygallery.com/artists/51-garry-fabian-miller/overview/https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/garry-fabian-miller

Since 2013, Fabian Miller has also worked with the weavers in the Dovecot Studio in Edinburgh, making gun tufted rugs (some of which have been acquired by the Standard Life Aberdeen Investment Bank for the foyer of their Edinburgh Head Office - see photograph above) and in 2017 a tapestry, based on the colours and shapes in his photographs. Probably his most important collaboration over the last ten years has been with John Bodkin a master of digital printing who has helped in the challenging process of colour correcting high resolution scans of Fabian Miller's Cibachrome prints, while trying to maintain as closely as possible the subtleties of their original appearance and surface. This allows them to be re-printed to archival standards as 'C'prints using the Lambda Lightjet printing system, for exhibition at a much larger scale. Some of these prints were recently exhibited at the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh who have also worked closely with Fabian Miller for many years (see previous post from 16 Dec 2019).Moving into the third decade of the 21st century, it is relatively unusual to find an internationally acclaimed photographer whose primary method of creating images is so completely dependent on a traditional wet darkroom process. This is all the more surprising on discovering that no Cibachrome papers have been manufactured since 2012. Cibachrome papers are relatively stable if correctly stored (in a freezer) and Fabian Miller had the foresight to stock up when the last batch was produced. This supply is running out and he is down to his last one hundred sheets. There may be a few individuals around the world who still have small stocks in storage but they are unlikely to become available and their archival status will be unpredictable. The Cibachrome process chemistry is if anything more difficult to store and although there are possible work arounds using monochrome developers and RA4 process bleach/fix, he has decided that when he completes his current project using his remaining stock, he will close his darkroom forever. A very well written account of the saga of the demise of Cibachrome/Ilfochrome is available online (Vincent 2018).Under the circumstances, Fabian Miller seems remarkably optimistic about the future. He has a large library of work already made and now has access to the skills required to work with this digitally. He stopped selling his Cibachrome originals some time ago to retain them for future projects and now only sells his work as Lambda Lightjet 'C'prints. Although his work has can appear very precise and controlled, his almost poetic relationship with the elemental forces which shape his connection to the land are still very apparent. He discovered very recently that the building in Bristol in which he had been brought up, was at one time owned by the publisher Joseph Cottle. In one of their well documented walking tours in the 1790's, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, stayed for several days with Cottle in Bristol, before crossing the Severn by ferry to travel up the Wye Valley to Tintern. It transpires that Dorothy Wordsworth slept in the bedroom, which in later years became the darkrooom in which he still remembers playing as a child, while his parents were printing their work. He is currently trying to work out if there is a way of using this in the generation of his next project.The importance of the darkroom and its role in the history of the photography which so dramatically transformed our interactions with the rest of the world, can perhaps only be fully appreciated by those who have experienced working in one. In an attempt to address this, Historic England spent several days with Fabian Miller in 2016, documenting his working process. He has also made arrangements with the V&A Museum that when he does close his darkroom, it will be dismantled and installed in their Photography section as a new exhibit for visitors to experience. His archive of darkroom notebooks will also be acquired by the museum to be made available to future researchers.In discussion following the lecture, he was asked if his experience of the demise of Cibachrome felt like coming to the end of a prolonged terminal illness. While agreeing that the end of Cibachrome was sad, he feels that the potential of digital photography is exciting and that it is probably still in its infancy, with much still to be explored. He feels that it is important that people understand that the invention of chemical photography was a seminal moment in world history and is encouraged by the fact that there are still people who are trying to keep it alive. He has been thinking for some time about the early experiments of Fox Talbot and his correspondence with John Herschel, wondering if there is any scope for further research into this source material for clues as to developing other new processes. Examples of Fabian Miller's work and links to interviews with him are available at the websites of the V&A Museum, the Ingleby Gallery and on his own site, at www.garryfabianmiller.com. Barnes M. and Fabian Miller G. (2005) 'Illumine'. Merell Publishing London.Barnes M. (2012) 'Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography'. Merell Publishing London.Fabian Miller G. (2010) 'The Colour of Time'. Black Dog Publishing, London.Fabian Miller G. (2019) 'Blaze" Ingleby, Edinburgh.Scully S (2007) 'The Walls of Aran' Thames and Hudson, London.https://www.inglebygallery.com/artists/51-garry-fabian-miller/overview/https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/garry-fabian-miller

Vincent D (2018) A Brief History of Cibachrome Online at: https://douglasvincent.com/ilfochrome/history.html Accessed 11 February 2020

Fabian Miller is a relatively unusual photographer, inasmuch that for the last 30 years he has worked without a camera, creating his images in the darkroom using only light, projected directly onto Cibachrome papers, which use a (now discontinued) direct positive dye-destruction chemical process, renowned for producing a very characteristic vivid colour pallette. The colours in his prints are created by passing the light through coloured liquids or oils in glass containers of various shapes and sizes. He stopped selling his Cibachrome original prints in 2009, retaining these now for use as his working archive (and ultimately destined for the Victoria and Albert museum collection in London). He now produces his gallery scale images in collaboration with the printer John Bodkin, using a hybrid process in which the scanned originals are processed and printed from a digital enlarger onto photosensitive colour paper, then developed and fixed chemically (Lamda 'C' prints).

Fabian Miller is a relatively unusual photographer, inasmuch that for the last 30 years he has worked without a camera, creating his images in the darkroom using only light, projected directly onto Cibachrome papers, which use a (now discontinued) direct positive dye-destruction chemical process, renowned for producing a very characteristic vivid colour pallette. The colours in his prints are created by passing the light through coloured liquids or oils in glass containers of various shapes and sizes. He stopped selling his Cibachrome original prints in 2009, retaining these now for use as his working archive (and ultimately destined for the Victoria and Albert museum collection in London). He now produces his gallery scale images in collaboration with the printer John Bodkin, using a hybrid process in which the scanned originals are processed and printed from a digital enlarger onto photosensitive colour paper, then developed and fixed chemically (Lamda 'C' prints). The main gallery in the Ingleby is a large single square room with a decorative but beautifully simple octagonal stained glass skylight at the centre of the ceiling.

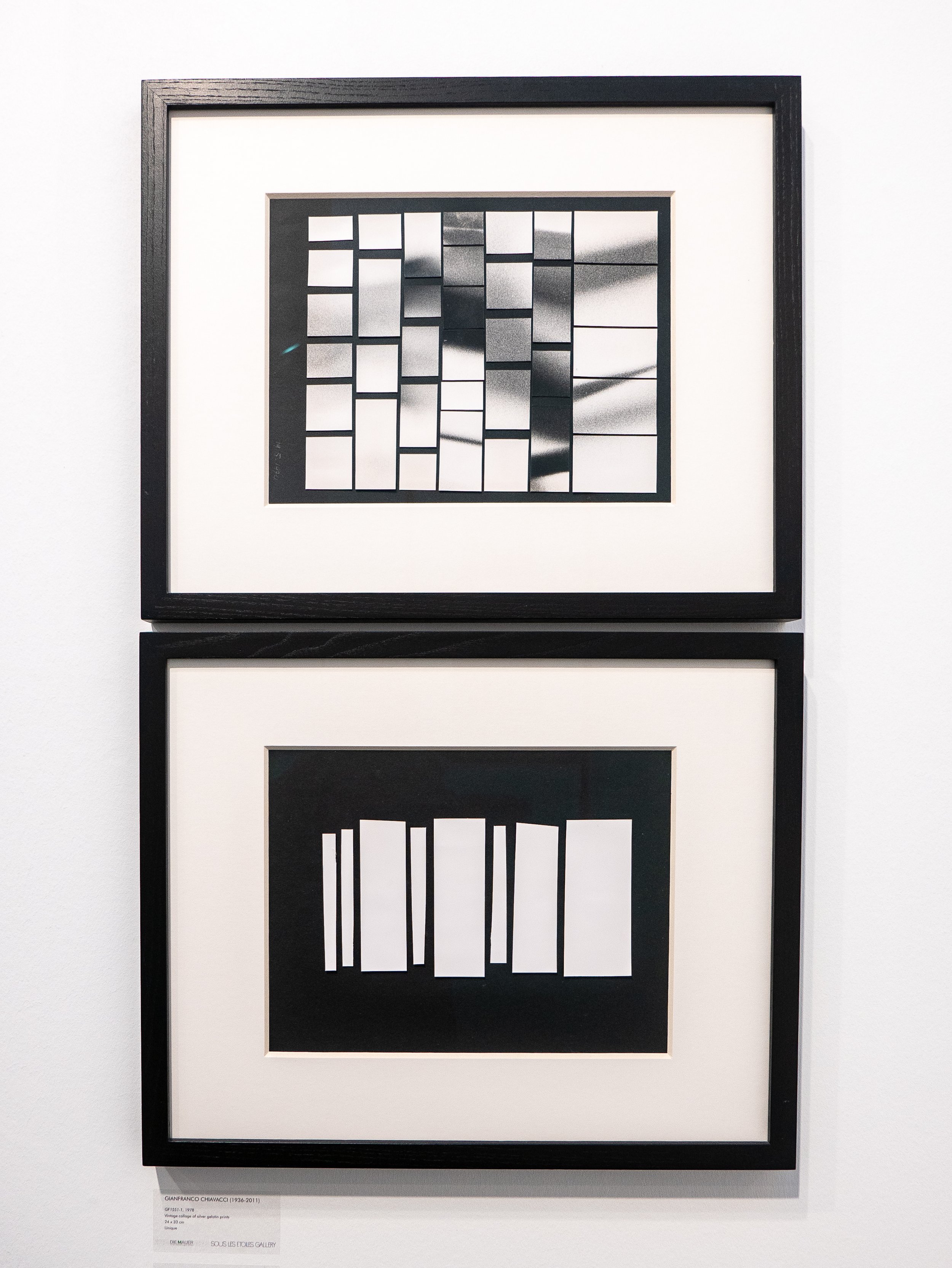

The main gallery in the Ingleby is a large single square room with a decorative but beautifully simple octagonal stained glass skylight at the centre of the ceiling.  The corridor and stairs lead past the gallery offices and upstairs to a smaller more intimate second gallery, laid out like a large domestic drawing room with a period fireplace, deep comfortable couches and a large viewing table. The framed prints on the walls in this gallery are representative samples of the other artists affiliated to the Ingleby, shown as they could appear in a potential buyers home.

The corridor and stairs lead past the gallery offices and upstairs to a smaller more intimate second gallery, laid out like a large domestic drawing room with a period fireplace, deep comfortable couches and a large viewing table. The framed prints on the walls in this gallery are representative samples of the other artists affiliated to the Ingleby, shown as they could appear in a potential buyers home. The gallery was visited late on a dark winter afternoon with the gallery lighting creating reflections on the glass frames so these photographs are presented simply to give an idea of the space and the scale of the work shown. They come nowhere near to reproducing the subtle detail or the true colours of the actual prints - the gallery website makes a much better job of this. Apart from their size and the vibrant colours, the striking feature of Fabian Miller's images is the luminescent high gloss finish, re-creating the unique almost metallic looking surface finish of Cibachrome, such that on first sight, it is difficult to be certain that they are prints and not in fact light boxes.

The gallery was visited late on a dark winter afternoon with the gallery lighting creating reflections on the glass frames so these photographs are presented simply to give an idea of the space and the scale of the work shown. They come nowhere near to reproducing the subtle detail or the true colours of the actual prints - the gallery website makes a much better job of this. Apart from their size and the vibrant colours, the striking feature of Fabian Miller's images is the luminescent high gloss finish, re-creating the unique almost metallic looking surface finish of Cibachrome, such that on first sight, it is difficult to be certain that they are prints and not in fact light boxes. This exhibition finishes on 20th December 2019.www.inglebygallery.comwww.garryfabianmiller.com* According to the Ingleby Gallery website, the Glasites are a strict religious group of Scottish Protestants, who following the teachings of the Reverend John Glas, broke away from the Church of Scotland in 1732. The building was designed by Alexander Black and built in the 1830's. It was last used as a place of worship in 1989 and was in the care of the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust prior to the Ingleby Gallery moving in.

This exhibition finishes on 20th December 2019.www.inglebygallery.comwww.garryfabianmiller.com* According to the Ingleby Gallery website, the Glasites are a strict religious group of Scottish Protestants, who following the teachings of the Reverend John Glas, broke away from the Church of Scotland in 1732. The building was designed by Alexander Black and built in the 1830's. It was last used as a place of worship in 1989 and was in the care of the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust prior to the Ingleby Gallery moving in.

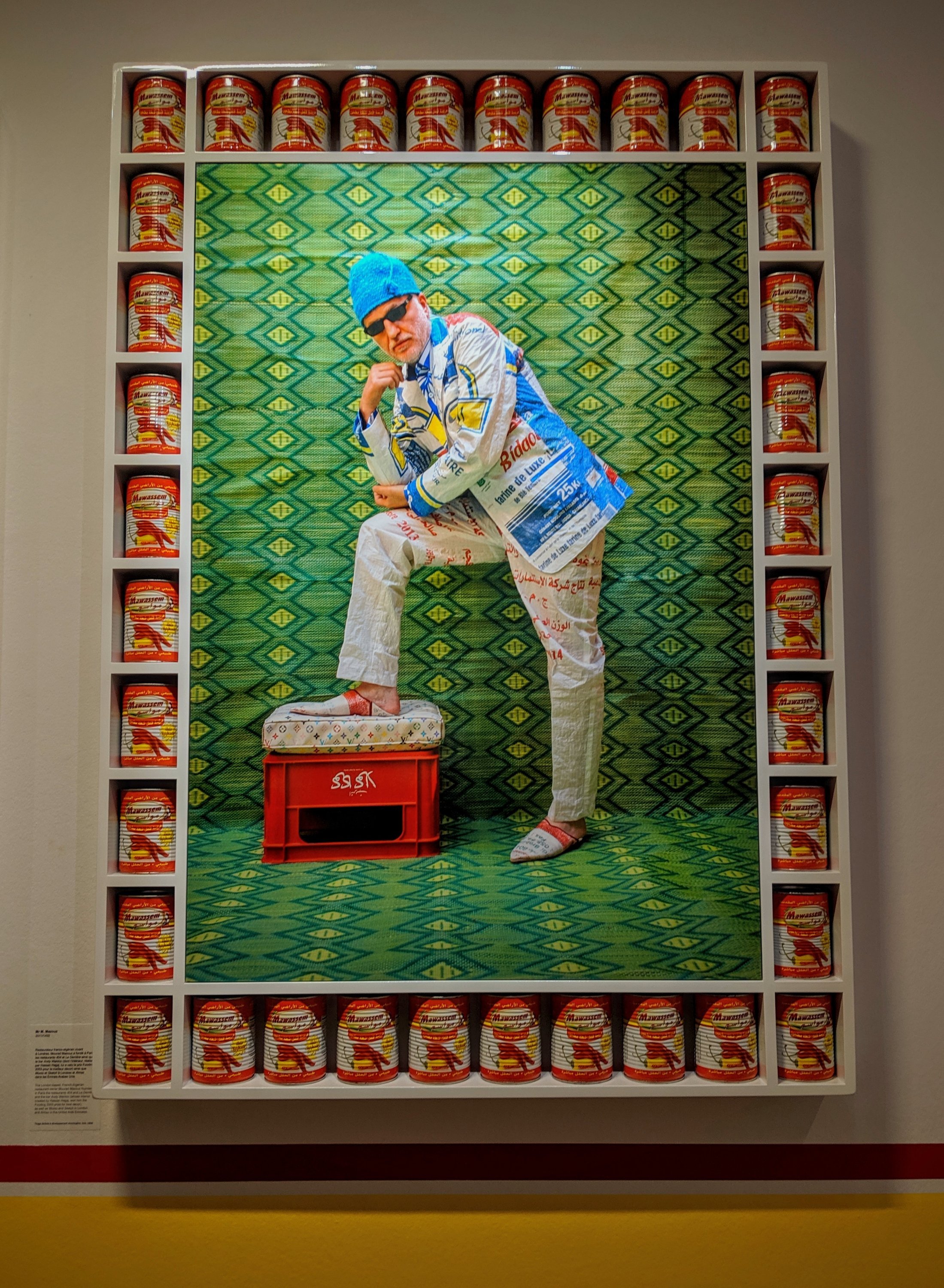

There is a strong thread of ironic humour running through his work but also a real sense of his pride in the communities he works in and his desire to see them represented fairly, in the positive light they deserve. There was a lot of excellent photography to see as running concurrently, the gallery was also showing some work by the female Moroccan photographers Zahrin Kahlo and Lamia Naji, with as a bonus a small selection of monochrome prints in a basement gallery by Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keita (both from Mali).www.mep-fr.orgwww.bjp-online.com/2019/10/hassan-hajjaj/

There is a strong thread of ironic humour running through his work but also a real sense of his pride in the communities he works in and his desire to see them represented fairly, in the positive light they deserve. There was a lot of excellent photography to see as running concurrently, the gallery was also showing some work by the female Moroccan photographers Zahrin Kahlo and Lamia Naji, with as a bonus a small selection of monochrome prints in a basement gallery by Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keita (both from Mali).www.mep-fr.orgwww.bjp-online.com/2019/10/hassan-hajjaj/

It was probably a mistake to try to see all of this in one day and the network of gallery stalls with a seething crowd of people actually makes it quite difficult to know if you have seen everything anyway. I spent seven hours going round the exhibits and tried to attend two of the Artist's Talks (one was in French a long way above my school days level), without stopping for a break as the queues for refreshment or food were enormous and I think I pretty much got there.

It was probably a mistake to try to see all of this in one day and the network of gallery stalls with a seething crowd of people actually makes it quite difficult to know if you have seen everything anyway. I spent seven hours going round the exhibits and tried to attend two of the Artist's Talks (one was in French a long way above my school days level), without stopping for a break as the queues for refreshment or food were enormous and I think I pretty much got there. If I did go again I would plan to spend at least two days, plan ahead cherry-picking what I really wanted to see and make sure I get in early for a seat for any of the talks that I didn't want to miss. Although relatively poorly

If I did go again I would plan to spend at least two days, plan ahead cherry-picking what I really wanted to see and make sure I get in early for a seat for any of the talks that I didn't want to miss. Although relatively poorly

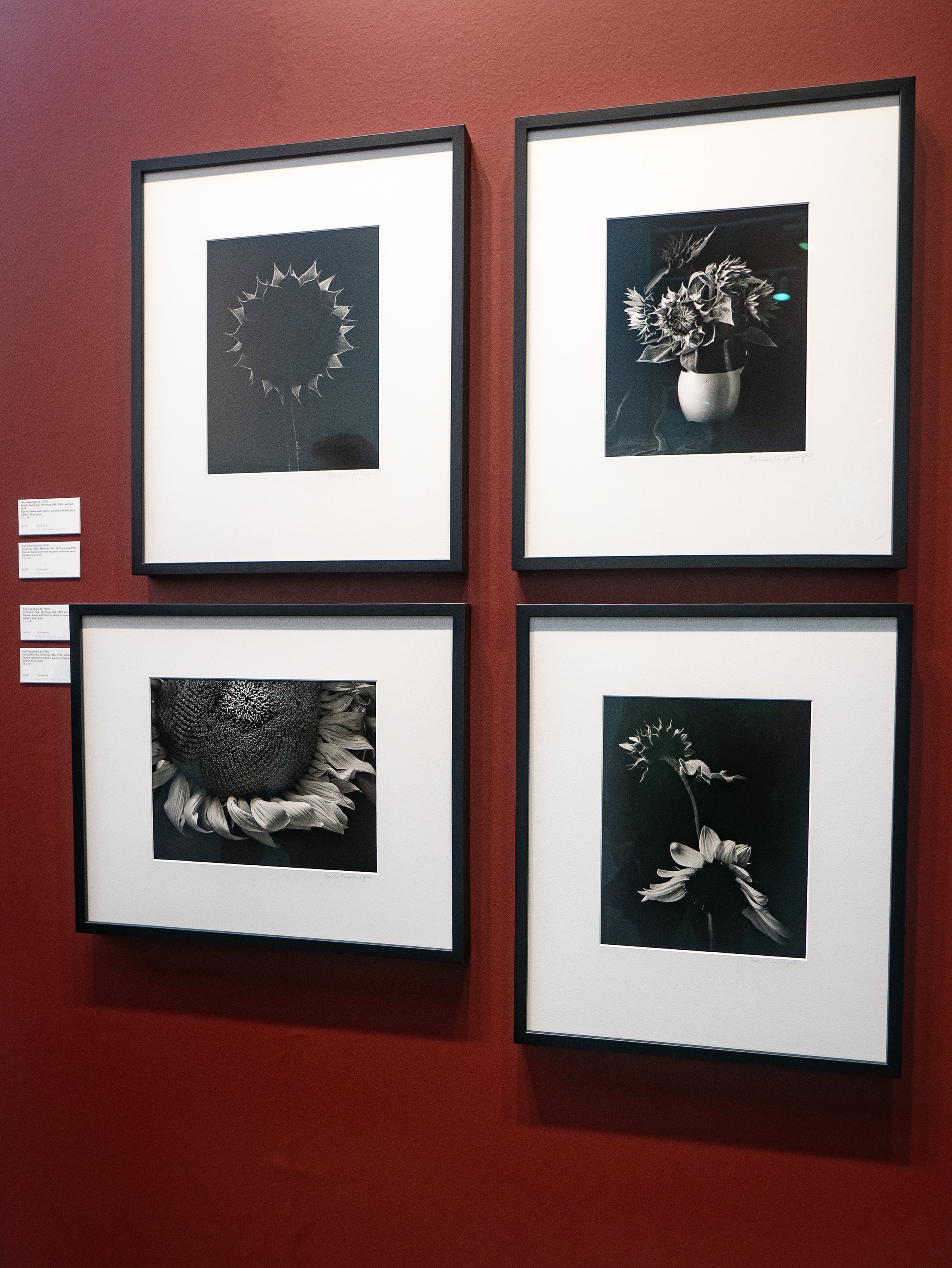

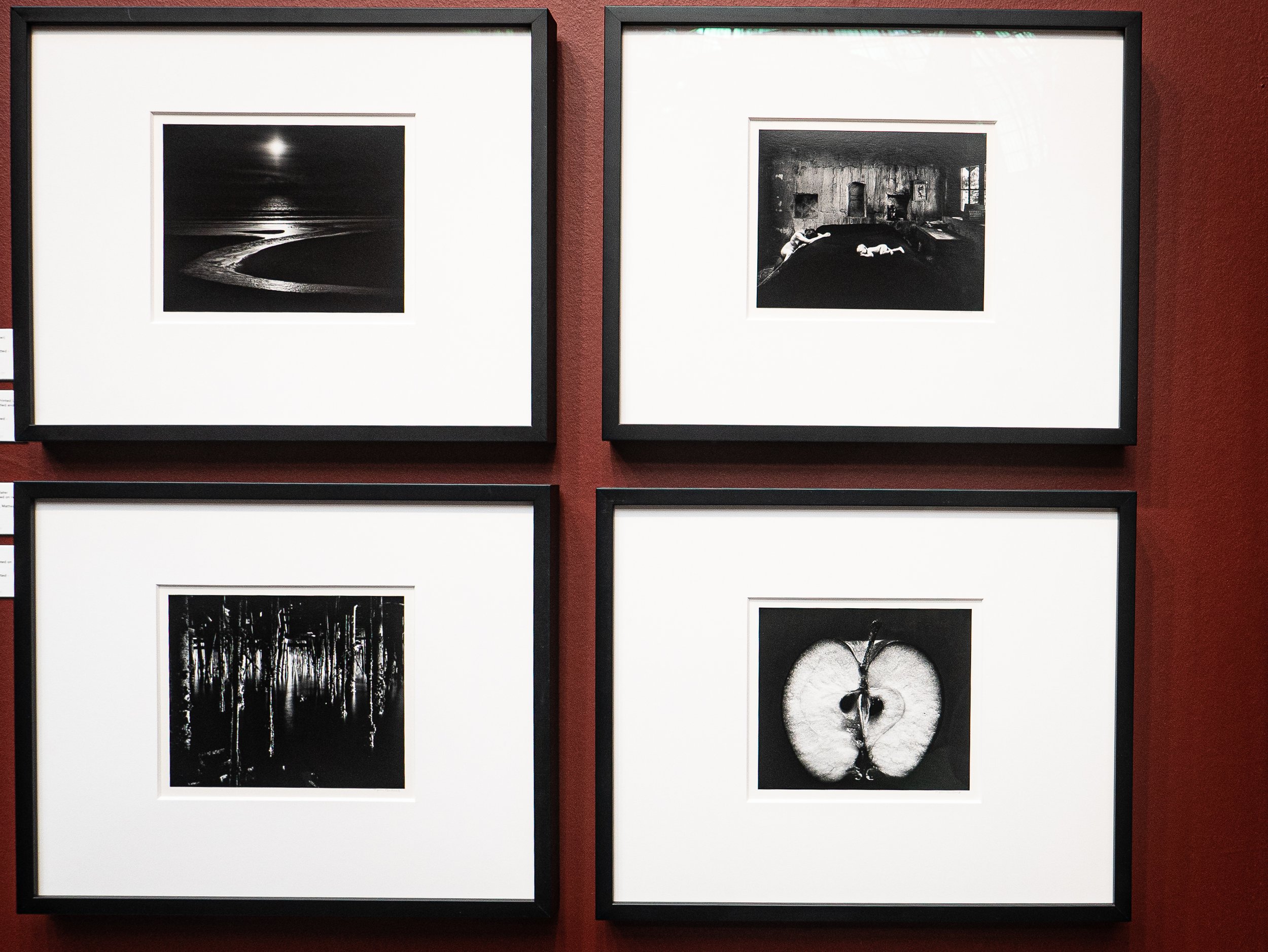

The other 'blockbuster' exhibition of photography currently showing in London, is a very substantial retrospective at Tate Britain of the work of Don McCullin, the first photographer to have been given this accolade. Built in 1892 (as the National Gallery of British Art), in contrast to the brutalist concrete of the South Bank, this is a more refined traditional Victorian art gallery with a classical portico entrance and a central dome. The layout of the exhibition also followed relatively traditional lines; exhibition quality monochrome silver gelatin prints (all printed by McCullin in his own darkroom), window mounted in plain black frames, evenly spaced as single images or in small groups and centered at eye level around the walls of eight substantial rooms. The photographs were presented in roughly chronological order, grouped geographically starting with his earliest images of gang members in east London in the late 1950's and moving on to images of conflict zones and famines in Berlin, Cyprus, the Middle East, Vietnam and Cambodia, Sudan, Biafra as well as those showing the effects of de-industrialisation, social deprivation, poverty and homelessness in London and Northern England. The captions were mostly simple place names but two or three images in each room had more detailed explanations, describing McCullin's own insights about the situations he found himself in.I already knew his work well from several of his books and having written an essay about his photography in Year 1 of the FdA course. There were no particular surprises on offer but the volume, range and power of the photographs was as impressive as anticipated, to the point of becoming almost overwhelming. These subject matter of these images is dark, moving, poignant, even shocking but the manifest empathy of the photographer for the individuals affected, the victims of these tragedies and his desire to ensure that their stories are told, totally dispels any notion of sensationalisation or exploitation. This impression is confirmed by Colin Jacobsen in his article about the exhibition in the British Journal of Photography, who also quotes Harold Evans, McCullin's former editor at The Sunday Times "He cared about the victims, the collateral damage" and "He couldn't express it in words, but he expressed it in his photography".Although the gallery was busy, the experience of being able to examine close up, the quality in the detail of these prints, from negatives exposed in often unimaginably challenging circumstances, made the journey worthwhile. This was particularly true of a group of his later photographs presented in the final room of the exhibition, some landscape images made near his home on the Somerset Levels.

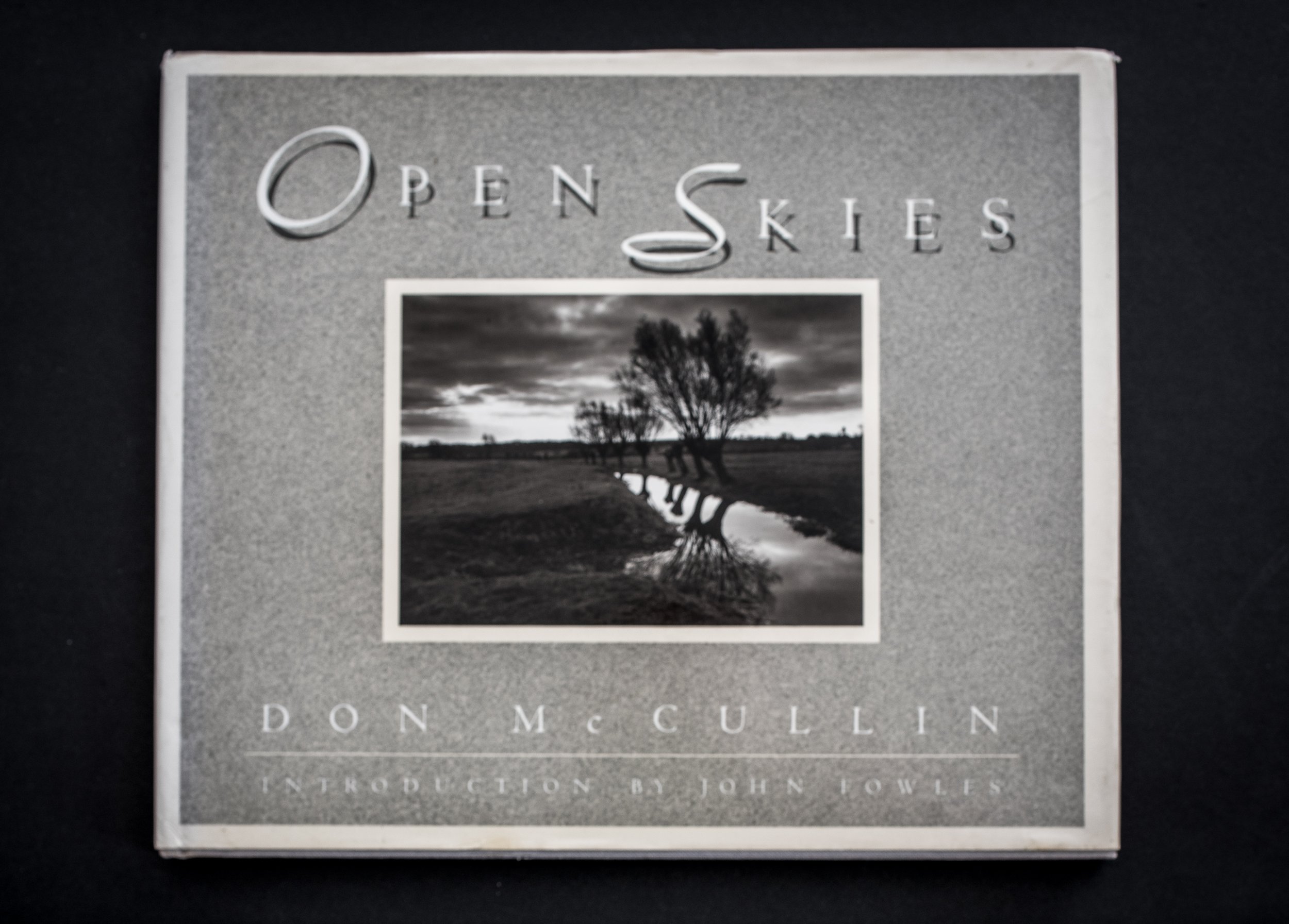

The other 'blockbuster' exhibition of photography currently showing in London, is a very substantial retrospective at Tate Britain of the work of Don McCullin, the first photographer to have been given this accolade. Built in 1892 (as the National Gallery of British Art), in contrast to the brutalist concrete of the South Bank, this is a more refined traditional Victorian art gallery with a classical portico entrance and a central dome. The layout of the exhibition also followed relatively traditional lines; exhibition quality monochrome silver gelatin prints (all printed by McCullin in his own darkroom), window mounted in plain black frames, evenly spaced as single images or in small groups and centered at eye level around the walls of eight substantial rooms. The photographs were presented in roughly chronological order, grouped geographically starting with his earliest images of gang members in east London in the late 1950's and moving on to images of conflict zones and famines in Berlin, Cyprus, the Middle East, Vietnam and Cambodia, Sudan, Biafra as well as those showing the effects of de-industrialisation, social deprivation, poverty and homelessness in London and Northern England. The captions were mostly simple place names but two or three images in each room had more detailed explanations, describing McCullin's own insights about the situations he found himself in.I already knew his work well from several of his books and having written an essay about his photography in Year 1 of the FdA course. There were no particular surprises on offer but the volume, range and power of the photographs was as impressive as anticipated, to the point of becoming almost overwhelming. These subject matter of these images is dark, moving, poignant, even shocking but the manifest empathy of the photographer for the individuals affected, the victims of these tragedies and his desire to ensure that their stories are told, totally dispels any notion of sensationalisation or exploitation. This impression is confirmed by Colin Jacobsen in his article about the exhibition in the British Journal of Photography, who also quotes Harold Evans, McCullin's former editor at The Sunday Times "He cared about the victims, the collateral damage" and "He couldn't express it in words, but he expressed it in his photography".Although the gallery was busy, the experience of being able to examine close up, the quality in the detail of these prints, from negatives exposed in often unimaginably challenging circumstances, made the journey worthwhile. This was particularly true of a group of his later photographs presented in the final room of the exhibition, some landscape images made near his home on the Somerset Levels. I have a second hand copy from America of his book 'Open Skies' published in 1989, which includes these photographs and have previously felt that they were so dark that they had been over-printed, blocking up the details in the shadow areas. Having now seen these photographs 'in the flesh', the detail in the shadows has been retained, the quality is superb and I can appreciate that the problem in the book is down to the reproduction of the images, emphasising the value in being able to get to see the original prints. In his introduction to the book, John Fowles speculates that the darkness of these images is a reflection of McCullin's 'state of mind' following his years of covering human tragedies all around the world, along with the tragedies of his own personal life.Thirty years further down the line and now aged 83, McCullin commented on this in a recent television documentary for BBC Four, confirming that as he has got older, he feels the need to make his prints darker, yet his mood now seems lighter and what was most apparent was his humility and that he still cares passionately about people, regardless of their background but especially the less fortunate among us.https://www.tate.org.uk/what's-on/tate-britain/exhibition/don-mccullinJacobsen, C., "Endframe, Don McCullin': British Journal of Photography, Issue 7882, p 98, April 2019.McCullin, D., 'Open Skies': Harmony Books, New York, 1989. (Originally published in Great Britain by Jonathon Cope).https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m0002dv0/don-mccullin-looking-for-england, Accessed on 10/4/2019

I have a second hand copy from America of his book 'Open Skies' published in 1989, which includes these photographs and have previously felt that they were so dark that they had been over-printed, blocking up the details in the shadow areas. Having now seen these photographs 'in the flesh', the detail in the shadows has been retained, the quality is superb and I can appreciate that the problem in the book is down to the reproduction of the images, emphasising the value in being able to get to see the original prints. In his introduction to the book, John Fowles speculates that the darkness of these images is a reflection of McCullin's 'state of mind' following his years of covering human tragedies all around the world, along with the tragedies of his own personal life.Thirty years further down the line and now aged 83, McCullin commented on this in a recent television documentary for BBC Four, confirming that as he has got older, he feels the need to make his prints darker, yet his mood now seems lighter and what was most apparent was his humility and that he still cares passionately about people, regardless of their background but especially the less fortunate among us.https://www.tate.org.uk/what's-on/tate-britain/exhibition/don-mccullinJacobsen, C., "Endframe, Don McCullin': British Journal of Photography, Issue 7882, p 98, April 2019.McCullin, D., 'Open Skies': Harmony Books, New York, 1989. (Originally published in Great Britain by Jonathon Cope).https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m0002dv0/don-mccullin-looking-for-england, Accessed on 10/4/2019

The Hayward gallery in the South Bank Centre in London is currently showing an exhibition of original monochrome analogue photographs made by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) between 1956 and 1962. Although from the age of eighteen, she had worked in fashion and advertising alongside her husband, the actor and photographer Allan Arbus, she did not embark on the work for which she is now well known, until she was in her early thirties. At that time, while she was studying with Lisette Model, she began to make photographs of people she met in the street in and around the less affluent areas of New York City and Coney Island. These images, best described as her early formative work, were made using 35mm film cameras printed at 6 x 9 inches by Arbus herself and two thirds of them have not been shown previously in the U.K.

The Hayward gallery in the South Bank Centre in London is currently showing an exhibition of original monochrome analogue photographs made by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) between 1956 and 1962. Although from the age of eighteen, she had worked in fashion and advertising alongside her husband, the actor and photographer Allan Arbus, she did not embark on the work for which she is now well known, until she was in her early thirties. At that time, while she was studying with Lisette Model, she began to make photographs of people she met in the street in and around the less affluent areas of New York City and Coney Island. These images, best described as her early formative work, were made using 35mm film cameras printed at 6 x 9 inches by Arbus herself and two thirds of them have not been shown previously in the U.K. As perhaps expected, the quality of the images does not equate with that of her much better known later medium format photographs but the gallery did not permit photography in this exhibition so I have no available examples to show. There was a small area, separate from the main body of the exhibition, showing a folio of ten of her medium format prints (printed at 20 x 20 inches) and the difference in quality was clearly evident. That said, the earlier photographs explored a wider range of subject matter, informal portraits, street photography, people in fairgrounds or at the beach, cinema and theatre audiences and people through restaurant windows. A few images appeared to be screen shots on television sets and there were some found still lives on wet pavements. Several of the prints showed pronounced grain effects and in some (especially the low-light images) the focus was quite soft but this imparted a degree of freshness or rawness to the work which appeared less planned or staged than her photographs from the mid 1960's onwards. This would be an important collection for anyone studying Diane Arbus, demonstrating the early stages of the evolution of her working practice.

As perhaps expected, the quality of the images does not equate with that of her much better known later medium format photographs but the gallery did not permit photography in this exhibition so I have no available examples to show. There was a small area, separate from the main body of the exhibition, showing a folio of ten of her medium format prints (printed at 20 x 20 inches) and the difference in quality was clearly evident. That said, the earlier photographs explored a wider range of subject matter, informal portraits, street photography, people in fairgrounds or at the beach, cinema and theatre audiences and people through restaurant windows. A few images appeared to be screen shots on television sets and there were some found still lives on wet pavements. Several of the prints showed pronounced grain effects and in some (especially the low-light images) the focus was quite soft but this imparted a degree of freshness or rawness to the work which appeared less planned or staged than her photographs from the mid 1960's onwards. This would be an important collection for anyone studying Diane Arbus, demonstrating the early stages of the evolution of her working practice. For my own research, perhaps the most striking aspect of this exhibition was the way in which the work was presented (I made the one photograph shown above before I noticed the small 'No Photography' sign on the plain wall on the right of the image). There were no photographs on the perimeter walls of the space, which were painted in a deep rich matt navy blue (almost black) colour. As shown, the main gallery contained about forty evenly spaced free standing pillars painted in matt white with one photograph only on each long side. The prints were traditionally window mounted in dark metallic pewter like frames and the immediate impressions created by the design were of light airiness and opulently high quality minimalist precision, with a hushed atmosphere indicating genuine reverence for the work being presented.Diane Arbus tragically took her own life in 1971 and I think she would have been pleased with this exhibition but although the gallery has gone to great lengths (and expense) to create an impressive setting for the photographs, I felt to an extent that the design almost overwhelmed the actual images, perhaps reinforcing my impression that this was not her best work. In the information at the gallery entrance, the curators explained that the work had not been arranged in any chronological order and that viewers should feel free to find their own route around the gallery at their own pace. This worked well while the gallery was initially quiet but it filled up quite quickly and I was conscious of people around me moving from pillar to pillar in different directions at different speeds to the extent that I felt under pressure to move on, to avoid holding them up. Although many were individually fascinating, the disparate selection of images were placed surprisingly randomly with no obvious attempt to formally sequence them. This could of course have been an attempt to subliminally re-create the feel of the circumstances in which they were created but overall it felt more like a triumph of style over substance.https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/diane-arbus-beginninghttps://www.biography.com/people/diane-arbus-9187461

For my own research, perhaps the most striking aspect of this exhibition was the way in which the work was presented (I made the one photograph shown above before I noticed the small 'No Photography' sign on the plain wall on the right of the image). There were no photographs on the perimeter walls of the space, which were painted in a deep rich matt navy blue (almost black) colour. As shown, the main gallery contained about forty evenly spaced free standing pillars painted in matt white with one photograph only on each long side. The prints were traditionally window mounted in dark metallic pewter like frames and the immediate impressions created by the design were of light airiness and opulently high quality minimalist precision, with a hushed atmosphere indicating genuine reverence for the work being presented.Diane Arbus tragically took her own life in 1971 and I think she would have been pleased with this exhibition but although the gallery has gone to great lengths (and expense) to create an impressive setting for the photographs, I felt to an extent that the design almost overwhelmed the actual images, perhaps reinforcing my impression that this was not her best work. In the information at the gallery entrance, the curators explained that the work had not been arranged in any chronological order and that viewers should feel free to find their own route around the gallery at their own pace. This worked well while the gallery was initially quiet but it filled up quite quickly and I was conscious of people around me moving from pillar to pillar in different directions at different speeds to the extent that I felt under pressure to move on, to avoid holding them up. Although many were individually fascinating, the disparate selection of images were placed surprisingly randomly with no obvious attempt to formally sequence them. This could of course have been an attempt to subliminally re-create the feel of the circumstances in which they were created but overall it felt more like a triumph of style over substance.https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/diane-arbus-beginninghttps://www.biography.com/people/diane-arbus-9187461 While in London last month I also visited the Photographers' Gallery where the two current exhibitions on show are 'Roman Vishniac Rediscovered' (in collaboration with the Jewish Museum of London) and 'All I Know is What's on the Internet' (a quote from Donald Trump). I will consider the second of these in a separate blog.

While in London last month I also visited the Photographers' Gallery where the two current exhibitions on show are 'Roman Vishniac Rediscovered' (in collaboration with the Jewish Museum of London) and 'All I Know is What's on the Internet' (a quote from Donald Trump). I will consider the second of these in a separate blog. The larger exhibition, on Levels 4 and 5 of the gallery is an extensive retrospective of the Russian born American photographer Roman Vishniac (1897-1990). Vishniac had moved from Moscow to Berlin to escape the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1920 and his best known body of work is a large social documentary portrait of the Jewish population of Eastern Europe, mainly Berlin and Warsaw in the inter-war years, coinciding with the evolution of modernism and the rise of fascism with the resultant persecution of these communities. It is a unique document of the dramatic changes in these societies from a atmosphere open to artistic expression and social multiculturalism to the sectarianism and oppression of the Nazi regime and the populations decimated by their policies.The layout of most of the exhibition is a traditional wall mounted chronological sequence of very fine vintage (and some newly re-printed) monochrome prints, including studio and candid portraits as well as street photography and images of agricultural workers. On escaping from Germany in the mid-1930's, he moved to the USA and quickly established a successful commercial portrait studio. His other interest was the photography of microscopic life forms and his pioneering work in colour photomicrography led to an academic career and professorships in biology and fine art photography in several American universities - a selection of these images were presented in a separate room from the main exhibition as a projected slide show along with several of his publications displayed in glass cases.The quality of his work is very impressive and the social documentary work is genuinely moving but aside from this and his imaginative use of atmospheric shadows, the relevance to my own current practice is of limited relevance.www.thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/roman-vishniac-rediscovered

The larger exhibition, on Levels 4 and 5 of the gallery is an extensive retrospective of the Russian born American photographer Roman Vishniac (1897-1990). Vishniac had moved from Moscow to Berlin to escape the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1920 and his best known body of work is a large social documentary portrait of the Jewish population of Eastern Europe, mainly Berlin and Warsaw in the inter-war years, coinciding with the evolution of modernism and the rise of fascism with the resultant persecution of these communities. It is a unique document of the dramatic changes in these societies from a atmosphere open to artistic expression and social multiculturalism to the sectarianism and oppression of the Nazi regime and the populations decimated by their policies.The layout of most of the exhibition is a traditional wall mounted chronological sequence of very fine vintage (and some newly re-printed) monochrome prints, including studio and candid portraits as well as street photography and images of agricultural workers. On escaping from Germany in the mid-1930's, he moved to the USA and quickly established a successful commercial portrait studio. His other interest was the photography of microscopic life forms and his pioneering work in colour photomicrography led to an academic career and professorships in biology and fine art photography in several American universities - a selection of these images were presented in a separate room from the main exhibition as a projected slide show along with several of his publications displayed in glass cases.The quality of his work is very impressive and the social documentary work is genuinely moving but aside from this and his imaginative use of atmospheric shadows, the relevance to my own current practice is of limited relevance.www.thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/roman-vishniac-rediscovered