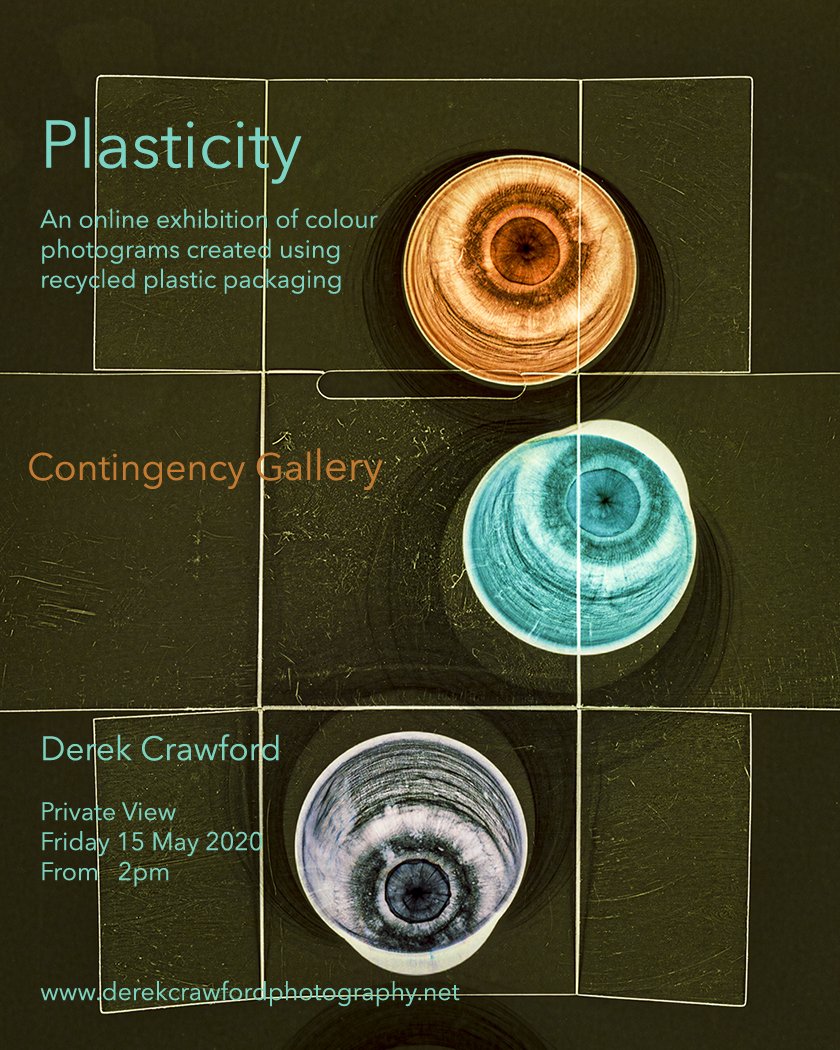

The spread of the Corona Virus epidemic in the UK in March 2019, with the ensuing government enforced social distancing measures and restrictions on movement and association, resulted in the effective lockdown of many public places including educational establishments, council buildings and galleries. This led in turn to the cancellation of our planned end of year exhibition - which would have formed the basis of the submission for our Final Major Project module to complete the requirements of my BA Degree in Photography at Coleg Llandrillo in North Wales.I found it impossible to dispel my deep conviction that a physical print format would be the most appropriate way to present the particular body of work, a series of colour photograms made using the contents of my recycle bin. To resolve this dilemma I decided to build a personal gallery space as a 1 in 12 scale maquette in which to exhibit physical prints, as originally planned. The exhibition is called PLASTICITY and can be viewed on my portfolio website at http://www.derekcrawfordphotography.net or using the direct link to a You Tube Video at youtube.com/watch?v=g-rnFbcAeXg

Garry Fabian Miller - Ingleby Gallery

The Ingleby Gallery is a small privately run gallery located since May 2018 in an A-listed former Glasite* Meeting House in the historic New Town in Edinburgh. The gallery has held and regularly shown work by the Dartmoor based photographer, Garry Fabian Miller since 2000 and their current ongoing exhibition - 'Midwinter Blaze' - is a small selection of his large scale abstract prints. Fabian Miller is a relatively unusual photographer, inasmuch that for the last 30 years he has worked without a camera, creating his images in the darkroom using only light, projected directly onto Cibachrome papers, which use a (now discontinued) direct positive dye-destruction chemical process, renowned for producing a very characteristic vivid colour pallette. The colours in his prints are created by passing the light through coloured liquids or oils in glass containers of various shapes and sizes. He stopped selling his Cibachrome original prints in 2009, retaining these now for use as his working archive (and ultimately destined for the Victoria and Albert museum collection in London). He now produces his gallery scale images in collaboration with the printer John Bodkin, using a hybrid process in which the scanned originals are processed and printed from a digital enlarger onto photosensitive colour paper, then developed and fixed chemically (Lamda 'C' prints).

Fabian Miller is a relatively unusual photographer, inasmuch that for the last 30 years he has worked without a camera, creating his images in the darkroom using only light, projected directly onto Cibachrome papers, which use a (now discontinued) direct positive dye-destruction chemical process, renowned for producing a very characteristic vivid colour pallette. The colours in his prints are created by passing the light through coloured liquids or oils in glass containers of various shapes and sizes. He stopped selling his Cibachrome original prints in 2009, retaining these now for use as his working archive (and ultimately destined for the Victoria and Albert museum collection in London). He now produces his gallery scale images in collaboration with the printer John Bodkin, using a hybrid process in which the scanned originals are processed and printed from a digital enlarger onto photosensitive colour paper, then developed and fixed chemically (Lamda 'C' prints). The main gallery in the Ingleby is a large single square room with a decorative but beautifully simple octagonal stained glass skylight at the centre of the ceiling.

The main gallery in the Ingleby is a large single square room with a decorative but beautifully simple octagonal stained glass skylight at the centre of the ceiling.  The corridor and stairs lead past the gallery offices and upstairs to a smaller more intimate second gallery, laid out like a large domestic drawing room with a period fireplace, deep comfortable couches and a large viewing table. The framed prints on the walls in this gallery are representative samples of the other artists affiliated to the Ingleby, shown as they could appear in a potential buyers home.

The corridor and stairs lead past the gallery offices and upstairs to a smaller more intimate second gallery, laid out like a large domestic drawing room with a period fireplace, deep comfortable couches and a large viewing table. The framed prints on the walls in this gallery are representative samples of the other artists affiliated to the Ingleby, shown as they could appear in a potential buyers home. The gallery was visited late on a dark winter afternoon with the gallery lighting creating reflections on the glass frames so these photographs are presented simply to give an idea of the space and the scale of the work shown. They come nowhere near to reproducing the subtle detail or the true colours of the actual prints - the gallery website makes a much better job of this. Apart from their size and the vibrant colours, the striking feature of Fabian Miller's images is the luminescent high gloss finish, re-creating the unique almost metallic looking surface finish of Cibachrome, such that on first sight, it is difficult to be certain that they are prints and not in fact light boxes.

The gallery was visited late on a dark winter afternoon with the gallery lighting creating reflections on the glass frames so these photographs are presented simply to give an idea of the space and the scale of the work shown. They come nowhere near to reproducing the subtle detail or the true colours of the actual prints - the gallery website makes a much better job of this. Apart from their size and the vibrant colours, the striking feature of Fabian Miller's images is the luminescent high gloss finish, re-creating the unique almost metallic looking surface finish of Cibachrome, such that on first sight, it is difficult to be certain that they are prints and not in fact light boxes. This exhibition finishes on 20th December 2019.www.inglebygallery.comwww.garryfabianmiller.com* According to the Ingleby Gallery website, the Glasites are a strict religious group of Scottish Protestants, who following the teachings of the Reverend John Glas, broke away from the Church of Scotland in 1732. The building was designed by Alexander Black and built in the 1830's. It was last used as a place of worship in 1989 and was in the care of the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust prior to the Ingleby Gallery moving in.

This exhibition finishes on 20th December 2019.www.inglebygallery.comwww.garryfabianmiller.com* According to the Ingleby Gallery website, the Glasites are a strict religious group of Scottish Protestants, who following the teachings of the Reverend John Glas, broke away from the Church of Scotland in 1732. The building was designed by Alexander Black and built in the 1830's. It was last used as a place of worship in 1989 and was in the care of the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust prior to the Ingleby Gallery moving in.

Royal Scottish Academy Annual Exhibition

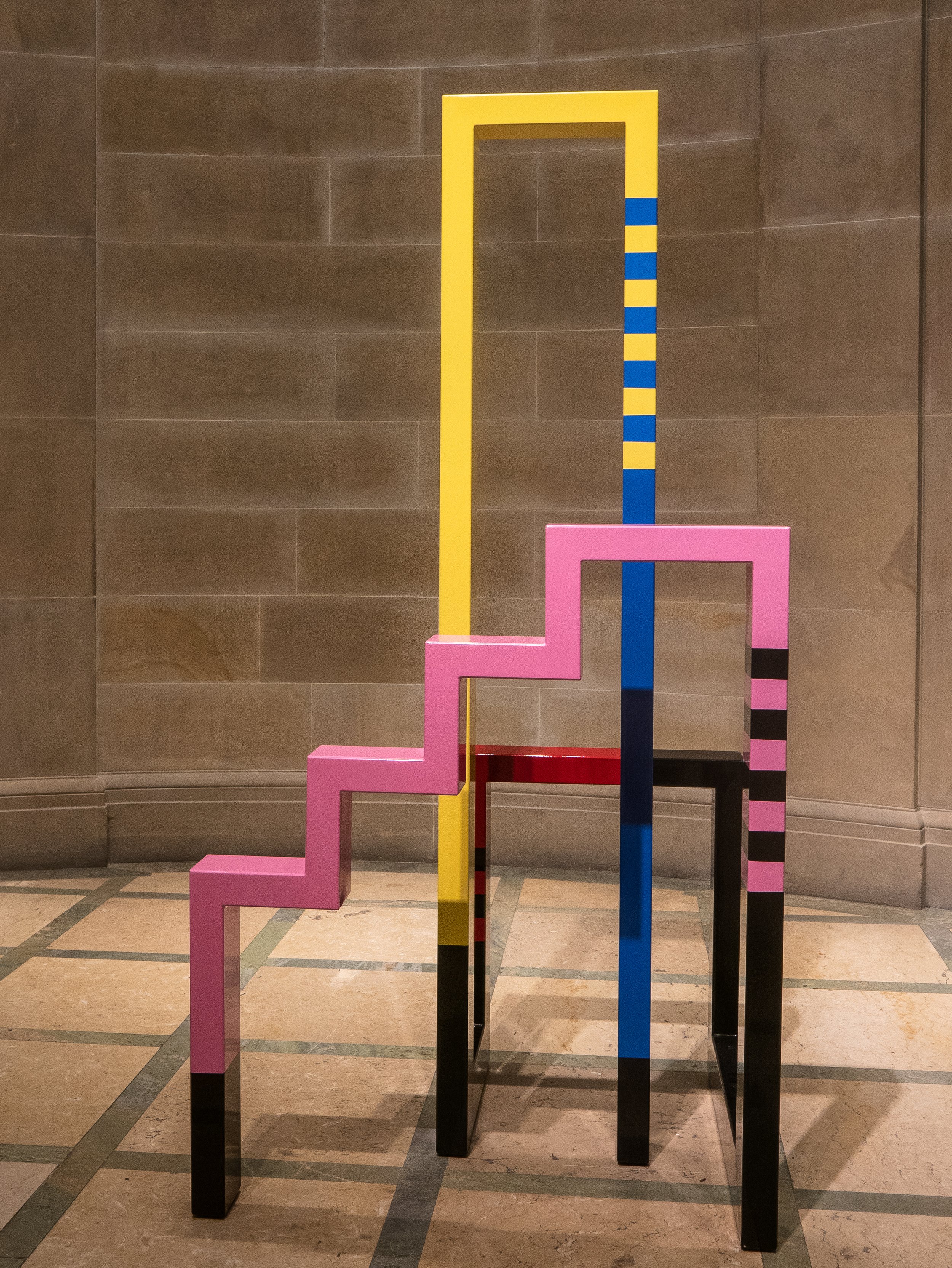

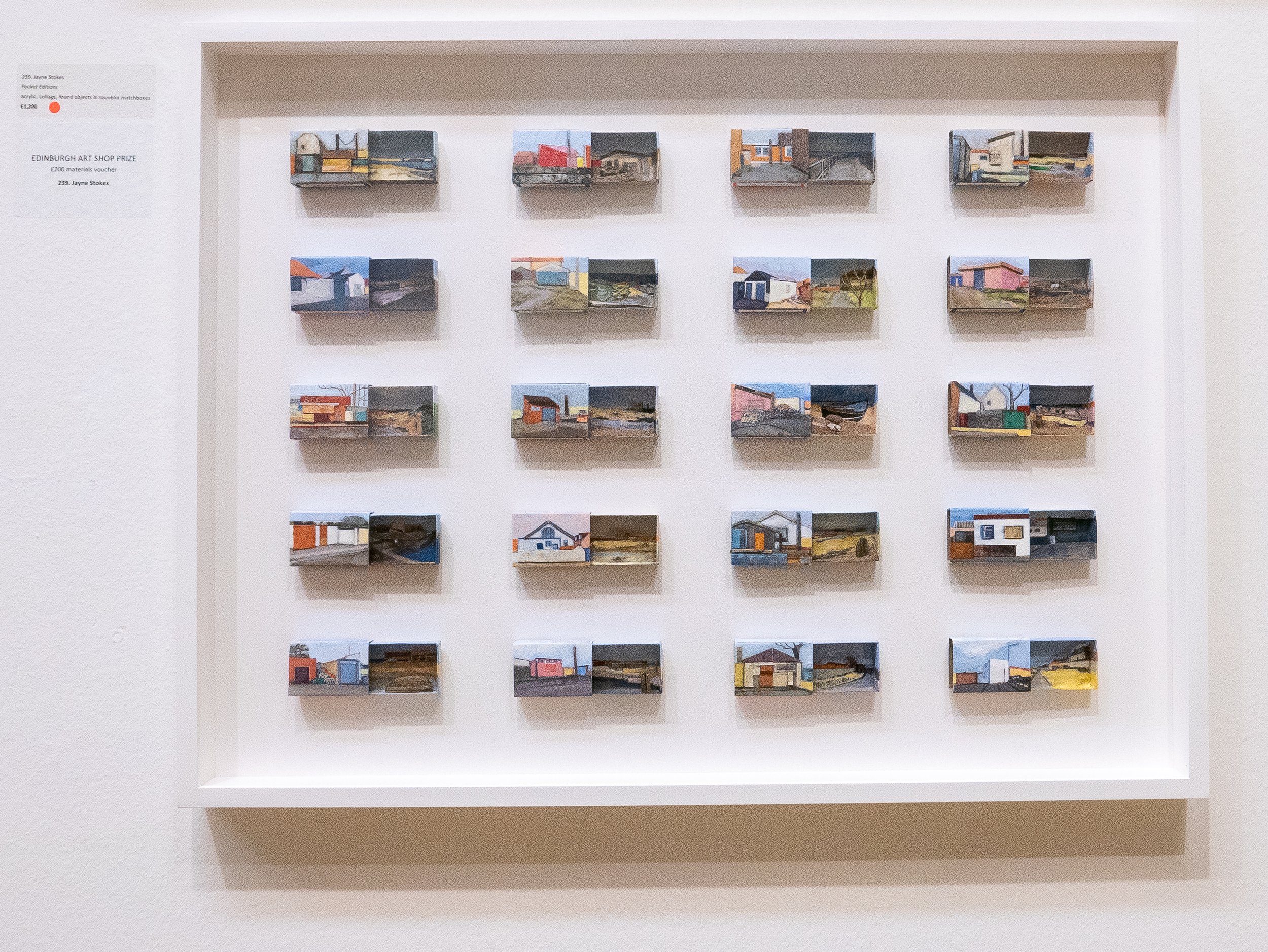

The 193rd Annual Exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, is showing currently in the National Gallery of Scotland on Princess Street, Edinburgh until 11th December, 2019. Entry is free and a generous selection of the work on show can be found on their very useful website. Most of the exhibits are paintings but there were also a reasonable number of sculptures, some installations and video art. The two rooms devoted to the architectural entries were particularly interesting.My own photographs below show some examples of just a few of the exhibits which particularly caught my eye.

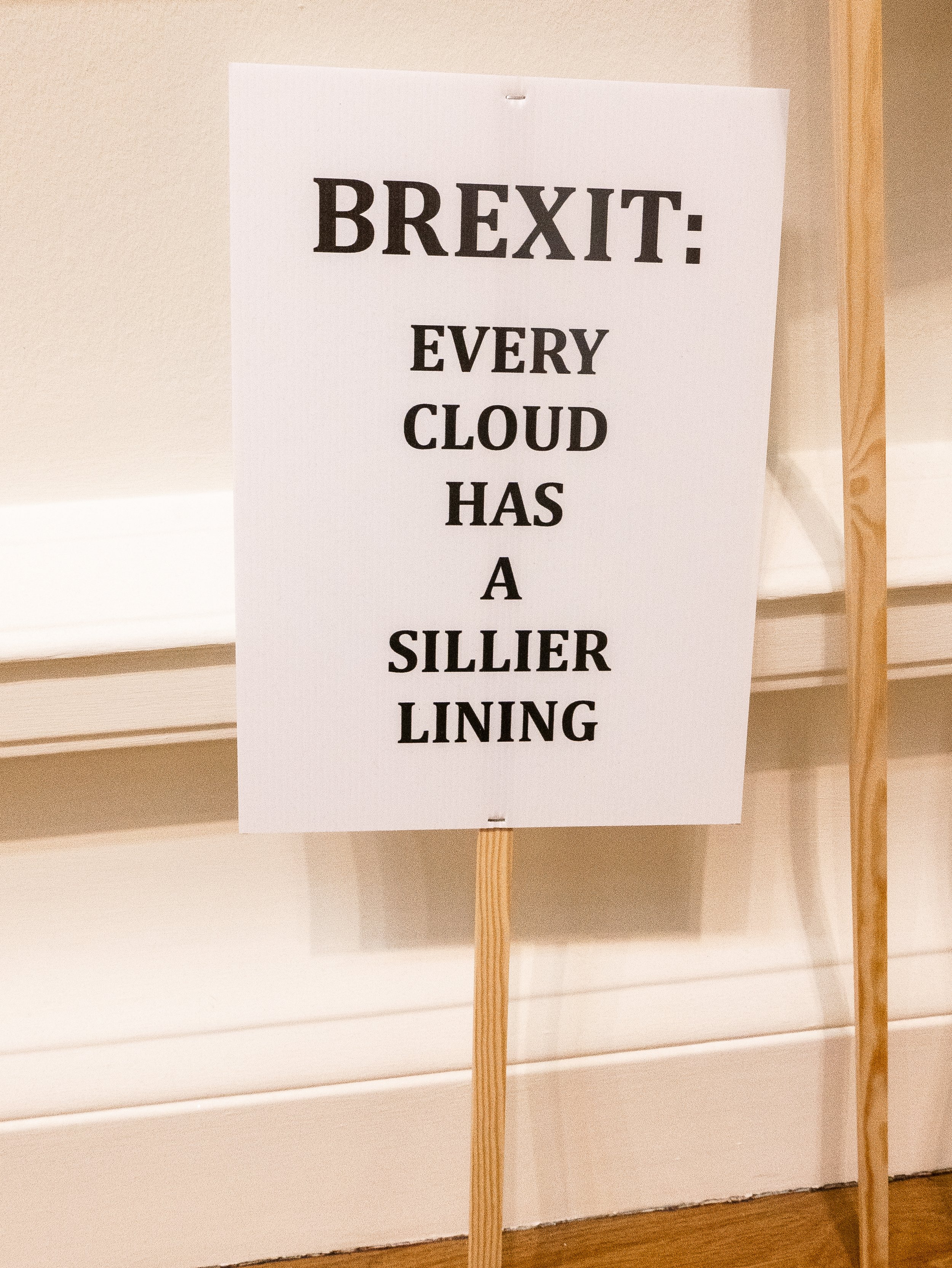

As a comment on the current state of play in UK politics, it seemed appropriate to show a closer look at the detail in this installation piece. The protester below who was photographed outside the gallery on the following morning appears to agree.

As a comment on the current state of play in UK politics, it seemed appropriate to show a closer look at the detail in this installation piece. The protester below who was photographed outside the gallery on the following morning appears to agree. https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/exhibitions/rsa-annual-exhibition-2019/

https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/exhibitions/rsa-annual-exhibition-2019/

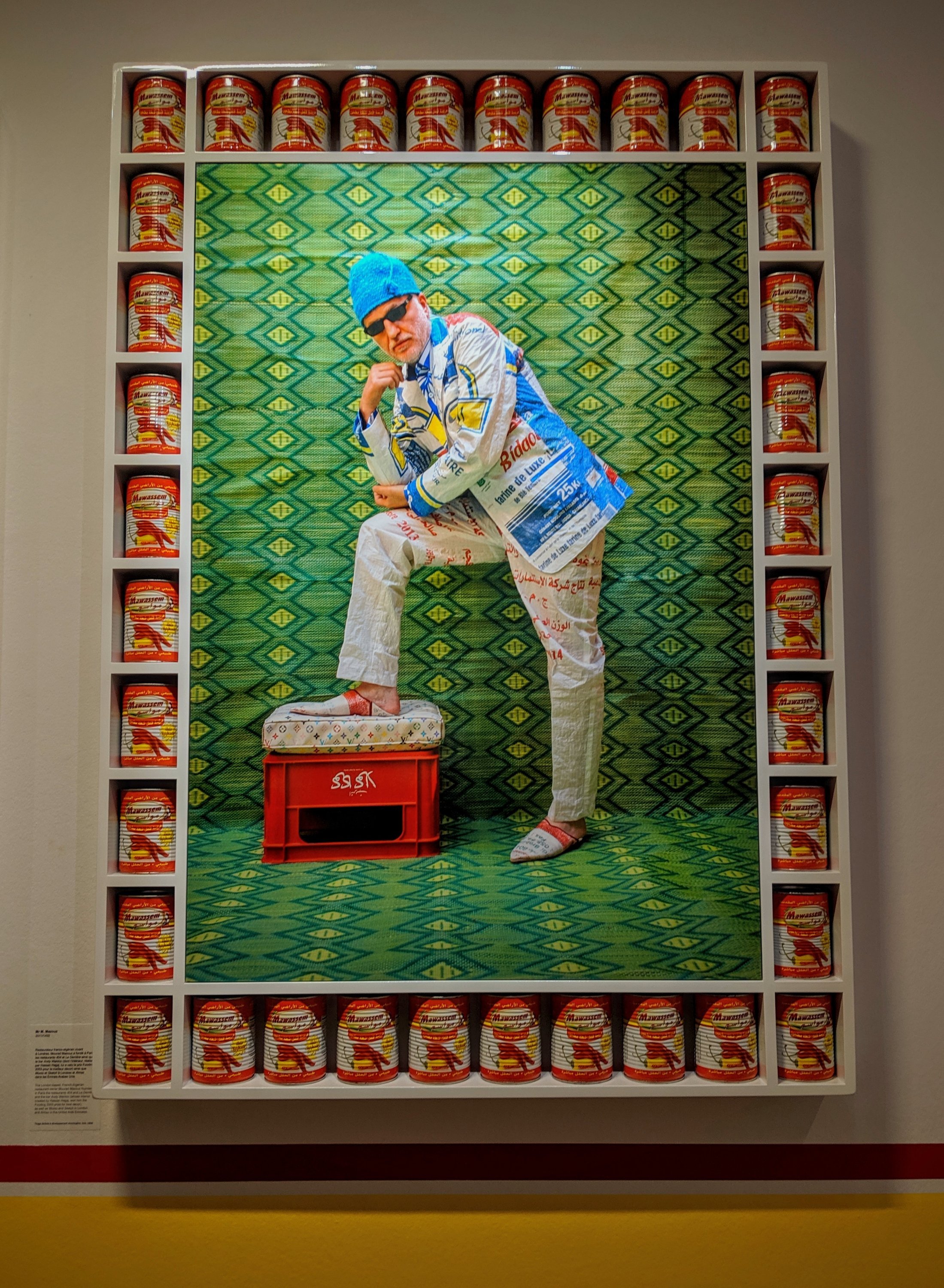

Hassan Hajjaj - Maison Européenne de la Photographie

The Maison Européenne de la Photographie is a permanent gallery in the Hotel Henault de Cantobre (built in 1706) in the Rue de Fourcy in central Paris. Owned by the city of Paris, it opened as a gallery devoted solely to photography in 1985 and the current director Simon Baker was appointed in 2018, having previously worked as Senior Curator (International Art - Photography) at Tate Modern in London. He has now initiated a programme aiming to cover a diverse range of contemporary photography. The main feature exhibition when I visited in November, was the work of London based photographer Hassan Hajjaj, who had emigrated there with his parents from Larache in Morocco, when he was aged thirteen.This was an extensive exhibition featuring some of his earlier black and white and hand coloured monochrome prints but much of the space was devoted to his large scale almost life size vividly colourful portraits of his friends and colleagues from a wide variety of artistic backgrounds. The other really striking feature drawing from his background was his imaginative use of highly stylised frames featuring tins of food, canned drinks, sauce bottles or bobbins of thread.

There is a strong thread of ironic humour running through his work but also a real sense of his pride in the communities he works in and his desire to see them represented fairly, in the positive light they deserve. There was a lot of excellent photography to see as running concurrently, the gallery was also showing some work by the female Moroccan photographers Zahrin Kahlo and Lamia Naji, with as a bonus a small selection of monochrome prints in a basement gallery by Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keita (both from Mali).www.mep-fr.orgwww.bjp-online.com/2019/10/hassan-hajjaj/

There is a strong thread of ironic humour running through his work but also a real sense of his pride in the communities he works in and his desire to see them represented fairly, in the positive light they deserve. There was a lot of excellent photography to see as running concurrently, the gallery was also showing some work by the female Moroccan photographers Zahrin Kahlo and Lamia Naji, with as a bonus a small selection of monochrome prints in a basement gallery by Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keita (both from Mali).www.mep-fr.orgwww.bjp-online.com/2019/10/hassan-hajjaj/

The World of Roger Ballen

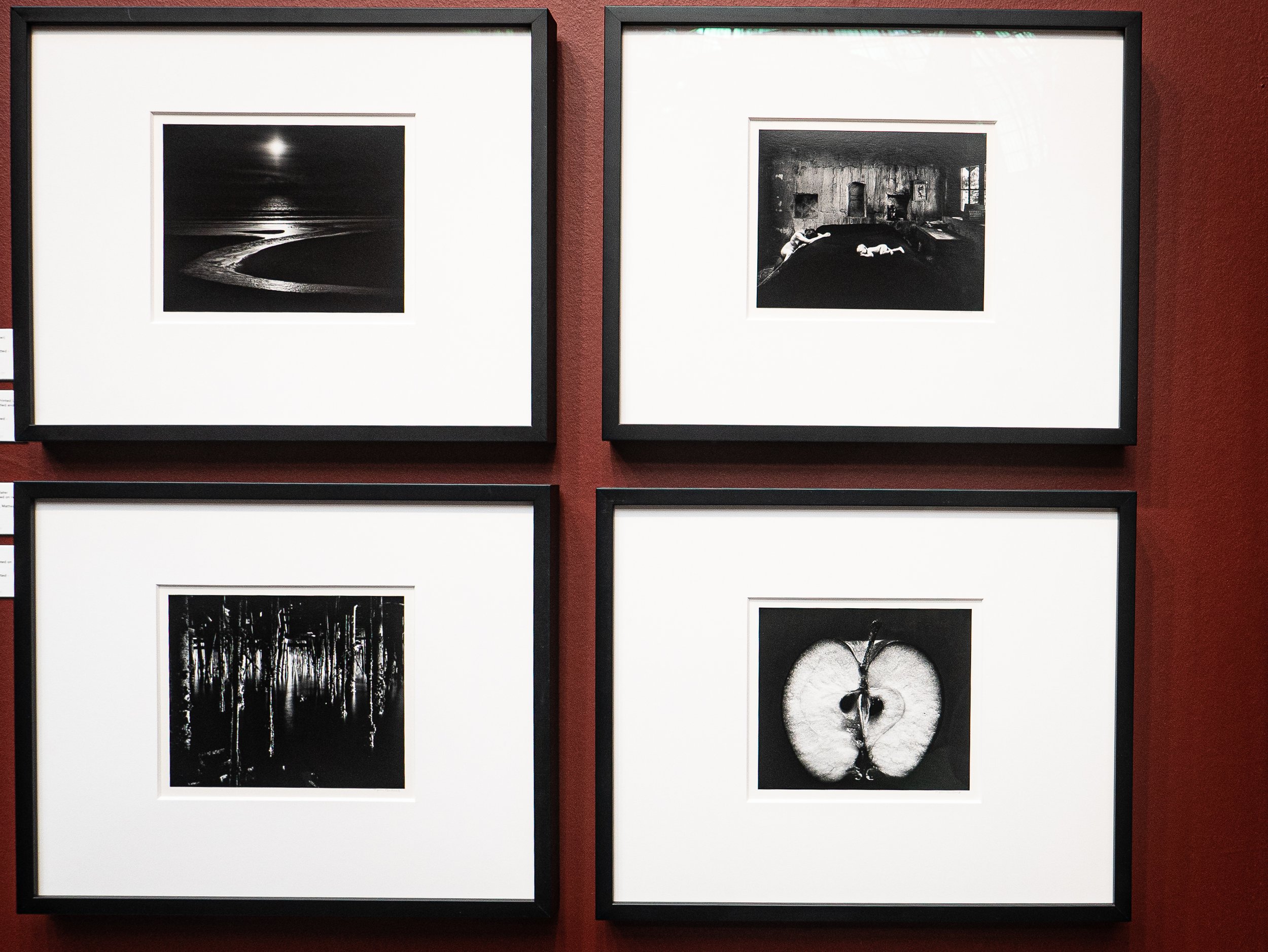

"The World of Roger Ballen" is an exhibition of the work of one of the most innovative contemporary photographers, showing currently and until July 2020 at the Halle St Pierre in Montmartre, Paris. The gallery itself is a light airy space on two levels, the upper galleries being accessed from a balcony overlooking the ground floor cafe and bookshop. It specialises in showing 'Art Brut' or outsider art, makes it particularly appropriate for this work. The current exhibition uses the upper floor for a fairly standard formal presentation of a generous selection Ballen's photographs as large framed prints, with some of his drawings directly on the walls and some of the props used in his work. Downstairs, the gallery contains recreations of several of the spaces he has photographed in the form of a series of vignettes, again using the photographer's own props, models, artworks and even a life sized model of himself with his Rolleiflex on a rotating pedestal. There was also a separate projection room showing a sequence of short films of the places and people he has worked with.

"The World of Roger Ballen" is an exhibition of the work of one of the most innovative contemporary photographers, showing currently and until July 2020 at the Halle St Pierre in Montmartre, Paris. The gallery itself is a light airy space on two levels, the upper galleries being accessed from a balcony overlooking the ground floor cafe and bookshop. It specialises in showing 'Art Brut' or outsider art, makes it particularly appropriate for this work. The current exhibition uses the upper floor for a fairly standard formal presentation of a generous selection Ballen's photographs as large framed prints, with some of his drawings directly on the walls and some of the props used in his work. Downstairs, the gallery contains recreations of several of the spaces he has photographed in the form of a series of vignettes, again using the photographer's own props, models, artworks and even a life sized model of himself with his Rolleiflex on a rotating pedestal. There was also a separate projection room showing a sequence of short films of the places and people he has worked with.

As can be seen above, the places and people he has photographed would perhaps best be described as being on the very fringes of society and the images are imaginative, darkly humorous, intriguing and sometimes challenging. The films shown at the gallery are also available on his website and perhaps give a better feel for the atmosphere in which his work is created. Ballen has recently been interviewed for the October edition of the British Journal of Photography by Michael Grieve and an interview with him at Paris Photo is also available on their websitewww.rogerballen.comhttps://www.hallesaintpierre.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/DP-HSP_Roger-Ballen.pdfGrieve M. 'The World according to Roger Ballen', British Journal of Photography, Issue No.7888, pp 38-49, October 2019.

As can be seen above, the places and people he has photographed would perhaps best be described as being on the very fringes of society and the images are imaginative, darkly humorous, intriguing and sometimes challenging. The films shown at the gallery are also available on his website and perhaps give a better feel for the atmosphere in which his work is created. Ballen has recently been interviewed for the October edition of the British Journal of Photography by Michael Grieve and an interview with him at Paris Photo is also available on their websitewww.rogerballen.comhttps://www.hallesaintpierre.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/DP-HSP_Roger-Ballen.pdfGrieve M. 'The World according to Roger Ballen', British Journal of Photography, Issue No.7888, pp 38-49, October 2019.

Paris Photo 2019

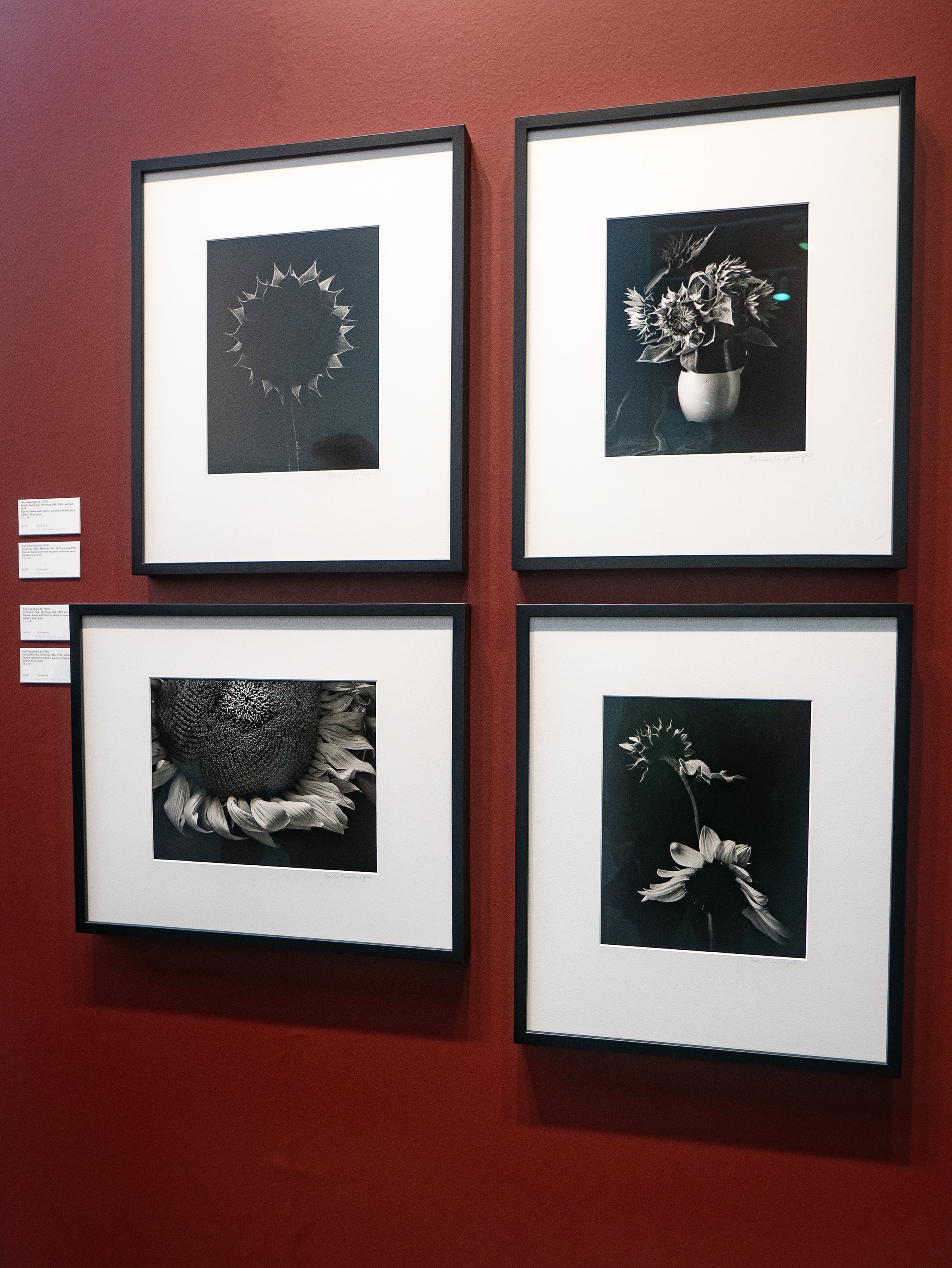

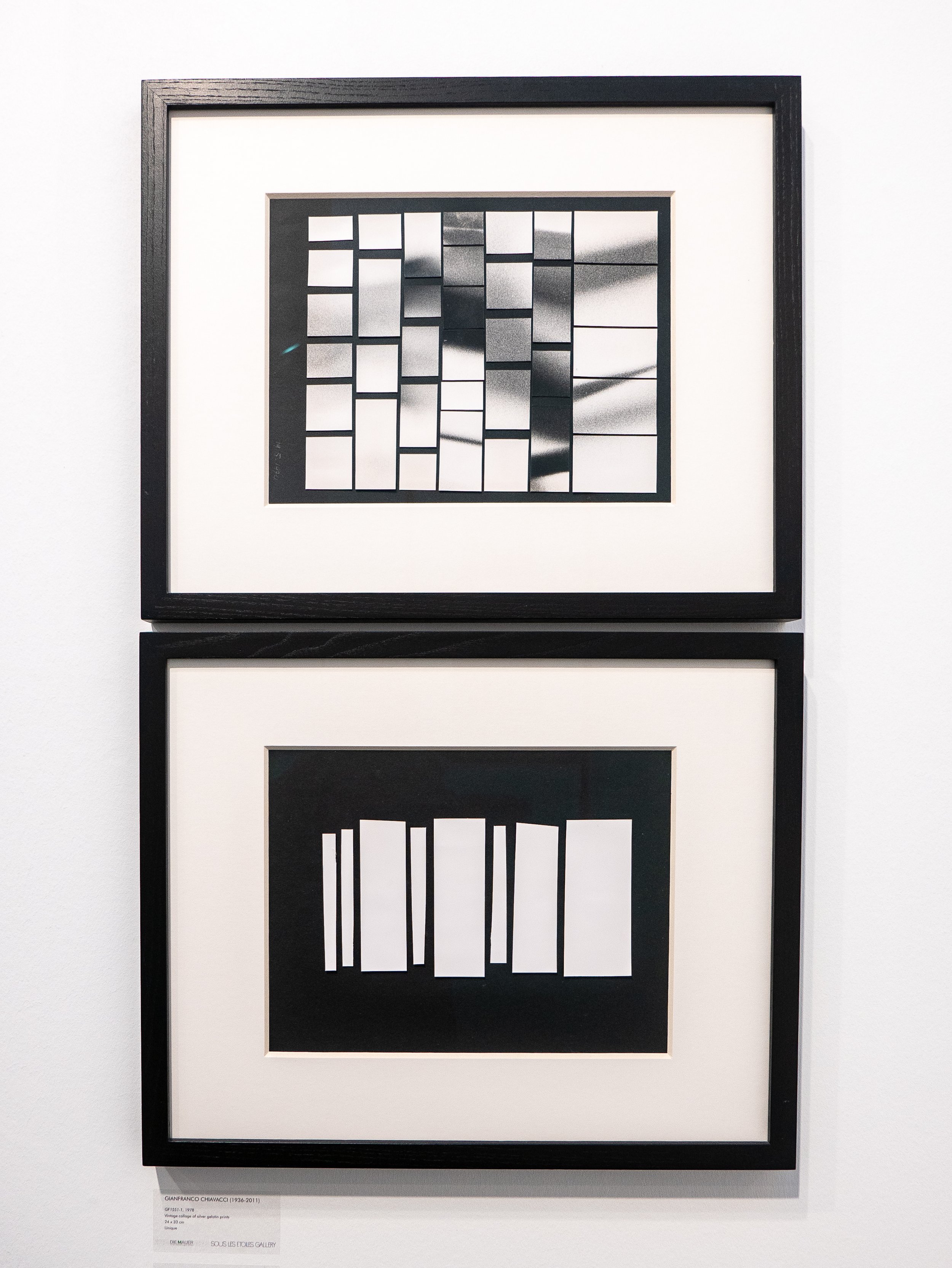

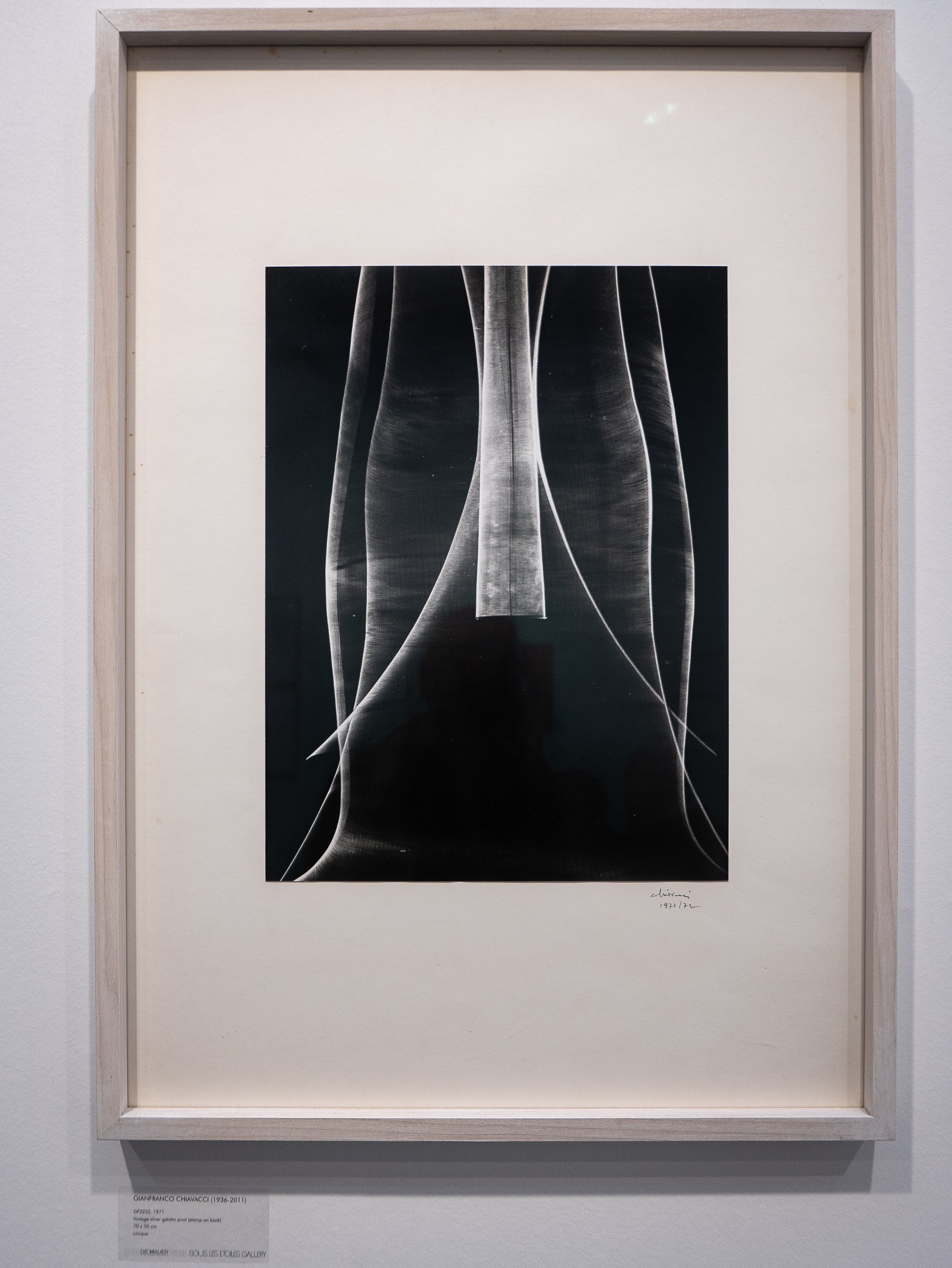

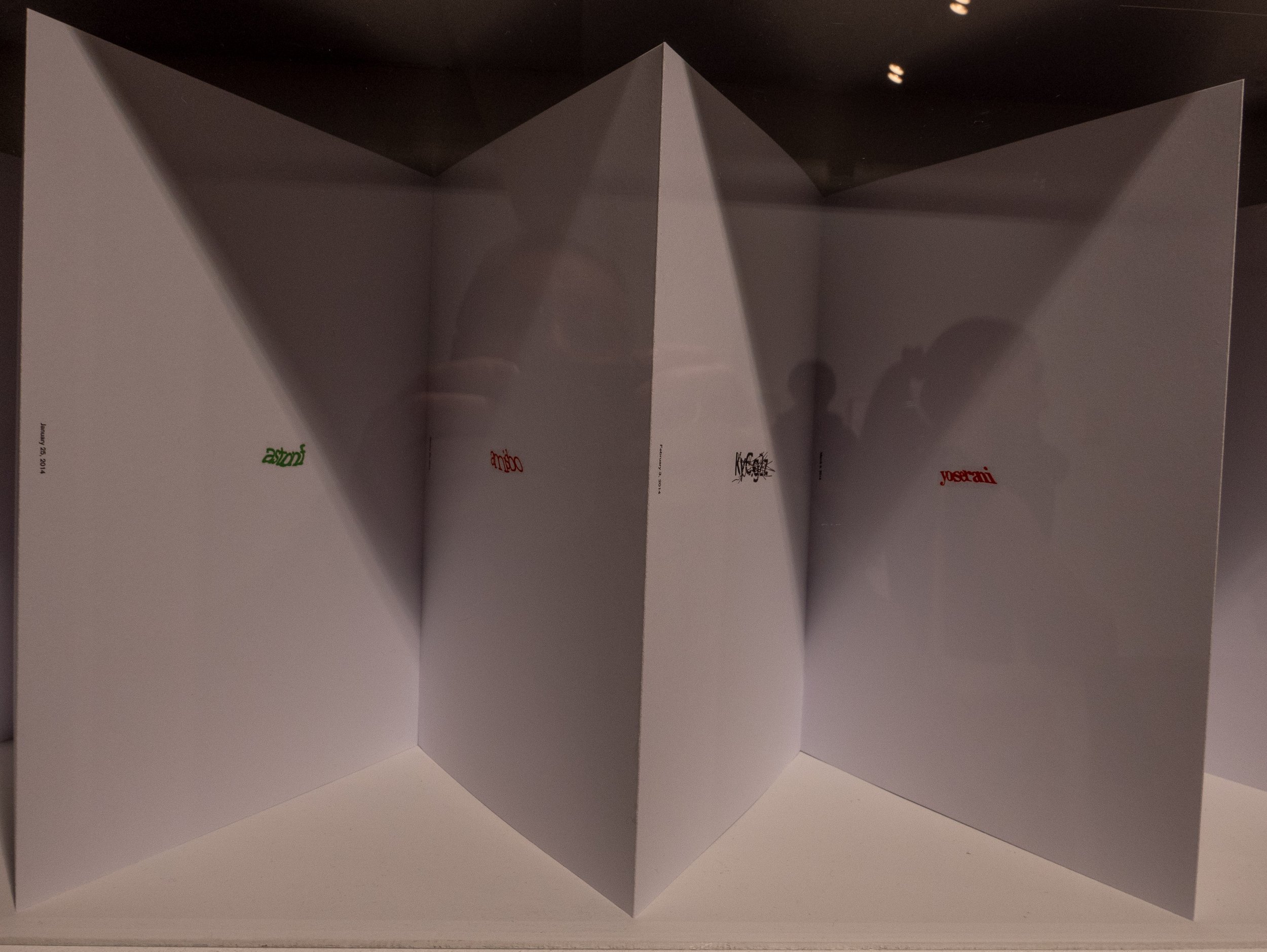

Spending a day at Paris Photo can be quite exhausting, due to the vast volume and wide range of photography on show but is one of the most stimulating ways of seeing at close hand, examples of a large selection of contemporary photography as well as original vintage prints by many of the finest photographers of the twentieth (and nineteenth) century. In practice, like Photo London, Paris Photo is essentially a four day long international dealers fair, showcasing largely fine art photography, with in addition a series of talks or interviews with several exhibiting photographers, a book fair and program of films, all under one (very large) roof.The large number of photographers represented makes it difficult to cover them comprehensively and unfair to single any one individual out. Selection of photos shown below represent a tiny fraction of what was available, concentrating on the more abstract or non-representational images, which I find myself increasingly drawn towards. They do not photograph well in the mixed lighting with lots of reflections and these are more of an aide memoire for myself and a record of the sorts of gallery layout that seemed effective, even in these relatively confined spaces. The selection includes a few original vintage prints by some of my personal favourites and several images by photographers that I have not previously encountered.

It was probably a mistake to try to see all of this in one day and the network of gallery stalls with a seething crowd of people actually makes it quite difficult to know if you have seen everything anyway. I spent seven hours going round the exhibits and tried to attend two of the Artist's Talks (one was in French a long way above my school days level), without stopping for a break as the queues for refreshment or food were enormous and I think I pretty much got there.

It was probably a mistake to try to see all of this in one day and the network of gallery stalls with a seething crowd of people actually makes it quite difficult to know if you have seen everything anyway. I spent seven hours going round the exhibits and tried to attend two of the Artist's Talks (one was in French a long way above my school days level), without stopping for a break as the queues for refreshment or food were enormous and I think I pretty much got there. If I did go again I would plan to spend at least two days, plan ahead cherry-picking what I really wanted to see and make sure I get in early for a seat for any of the talks that I didn't want to miss. Although relatively poorly organised, the Paris Photo website is an excellent ongoing resource with videos of many of the interviews from this and from previous years.https://www.parisphoto.com/en/Home/

If I did go again I would plan to spend at least two days, plan ahead cherry-picking what I really wanted to see and make sure I get in early for a seat for any of the talks that I didn't want to miss. Although relatively poorly organised, the Paris Photo website is an excellent ongoing resource with videos of many of the interviews from this and from previous years.https://www.parisphoto.com/en/Home/

Fingertips in Time - John Hedley

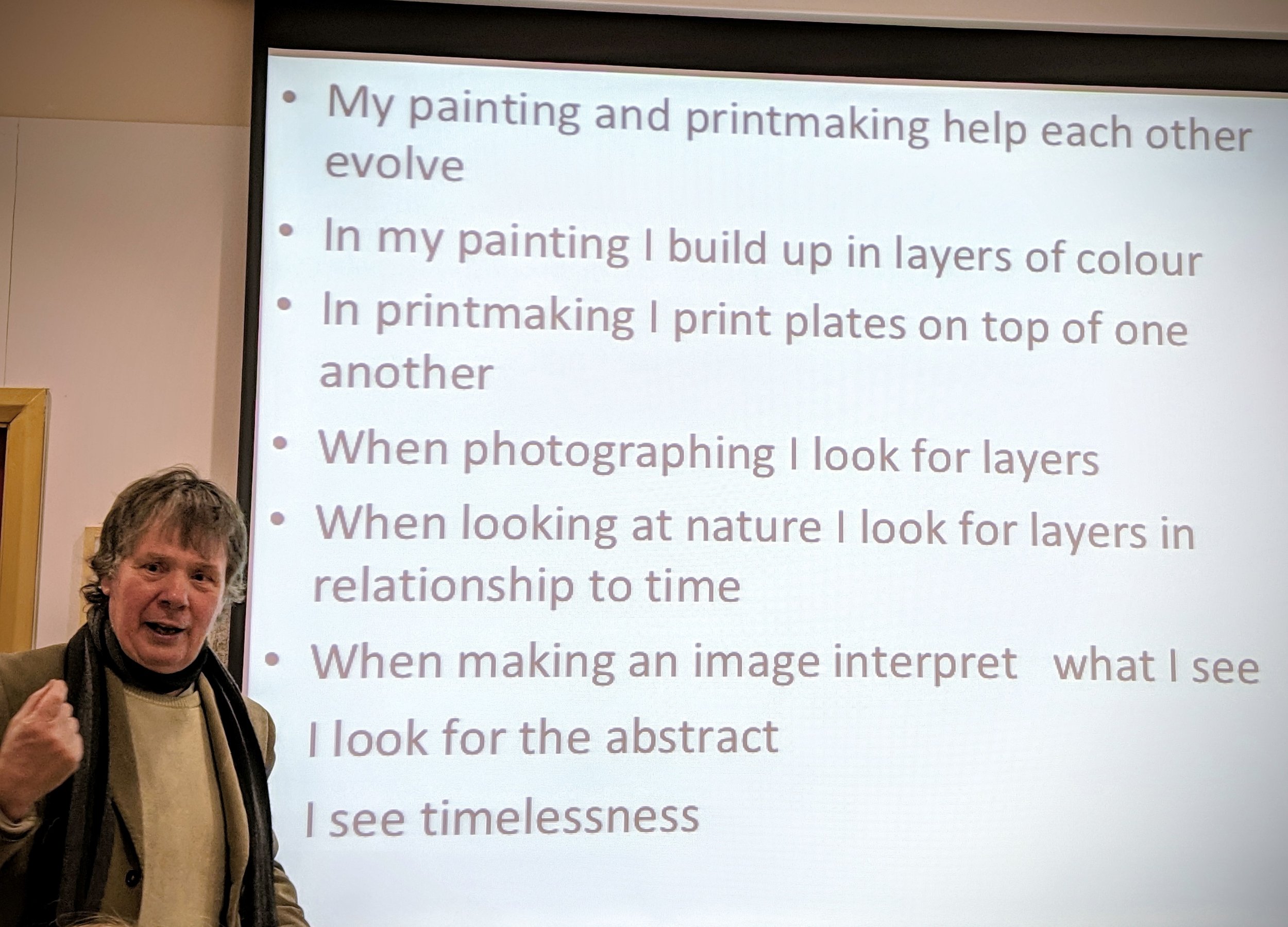

The painter and printmaker John Hedley gave a talk on the work in his exhibition 'Fingertips in Time' at Oriel Colwyn on Thursday 7th March 2019. The exhibited images fall into two series, one of trees presented as monochrome prints which looked almost like charcoal sketches and the other, a series of multicoloured print studies of volcanic rock formations from two sites, one at Llandwyn Island on Anglesey and the other in Crete. John talked about the techniques he used in making these and also more extensively about his work in general including his paintings, sculpture and work with mixed media. My interest in his processes relates to his use of digital camera photographs as the starting point and how he went about transforming these into intaglio prints. He explained that he prints the photographs as a positive image at high resolution (600 dpi bitmapped) onto acetate, using an A3 inkjet photo quality printer. The acetate is then exposed in a UV light box (Natgraph) onto a photopolymer etching plate (Solar Plate), which when processed and prepared (polished) can be inked up for printing onto dampened paper in a press. He explained that until recently, he had been wary of using photography as he felt this was almost like cheating. When he started using a digital SLR camera he discovered that the learning process was more complicated than he had anticipated; the main difficulty being obtaining a perfect tonal range which would be compatible with his printmaking processes. After a fair amount of "learning by mistakes" he has found that photography and image processing (layering in Photoshop) is now influencing his painting which has become "more abstract, in a round about way". He feels the main difference between most photographers and painters is that photographers feel they need to know what the end result will be at the time they press the shutter - i.e. classic 'pre-visualisation' as advocated by Ansel Adams (Schaefer, 1992) and the f64 group (and most photographers since then). In his printmaking, especially with multiple layers of coloured inks, he seldom knows what it will look like when finished and part of the process of abstraction is that the image evolves layer by layer, as it is being made.

He explained that until recently, he had been wary of using photography as he felt this was almost like cheating. When he started using a digital SLR camera he discovered that the learning process was more complicated than he had anticipated; the main difficulty being obtaining a perfect tonal range which would be compatible with his printmaking processes. After a fair amount of "learning by mistakes" he has found that photography and image processing (layering in Photoshop) is now influencing his painting which has become "more abstract, in a round about way". He feels the main difference between most photographers and painters is that photographers feel they need to know what the end result will be at the time they press the shutter - i.e. classic 'pre-visualisation' as advocated by Ansel Adams (Schaefer, 1992) and the f64 group (and most photographers since then). In his printmaking, especially with multiple layers of coloured inks, he seldom knows what it will look like when finished and part of the process of abstraction is that the image evolves layer by layer, as it is being made. Expanding on this, he explained that in deciding what to photograph he looks for the the most obscure and abstract things he can find, often now looking in nature for visual representations of layers; one tree in front of others, shadows on rocks or sand, layers in dead wood or rock formations, layers in time. In interpreting what he can see, he is taking from nature then playing and abstracting from it. He described this process as "being like building with Lego - start with the finished object - take it apart then re-build it - it will look similar but not exactly the same".To my surprise, I found that I had more in common with his approach than I had expected. In discussion with the audience, he talked of shadows in art as having ambiguity, transience - similar to the feelings I have been trying to capture in my photographs of shadows. I had not previously grasped the significance of layers but in many of my images, that could be what gives them the impression of texture. I felt comfortable with his explanations of abstraction, a concept I have had difficulty fully understanding previously. He is clearly happy now using a hybrid of digital photography and traditional printing, feeding contemporary technology into long established analogue processes. He is going to be in Greece for the next couple of months but has offered to let some of us visit his studio to share his technical knowledge. Having never seen photo-etching in practice or intaglio prints being made, I still have some difficulty in understanding exactly how it works and this is now on my list to do over the summer. I am sure that the learning curve for developing his printmaking skills was much steeper and longer than it took him to get what he needed from digital photography but I am still interested in printing digital negatives on acetate for use with historical U-V light based photographic processes and his advice on file preparation and printing technique could be invaluable.His final comment on his acceptance of photography as a tool for image making was to concede that "the mobile phone has become the sketch-book of the 21st century".The images used to illustrate this post were captured on my mobile phone camera.Schaefer JP (1999) 'Visualisation: The Art of Seeing a Photograph' In: Ansel Adams Guide - Basic Techniques of Photography Book (1); Revised edition, Boston-New York-London, Little, Brown and Company, pp 131-134.

Expanding on this, he explained that in deciding what to photograph he looks for the the most obscure and abstract things he can find, often now looking in nature for visual representations of layers; one tree in front of others, shadows on rocks or sand, layers in dead wood or rock formations, layers in time. In interpreting what he can see, he is taking from nature then playing and abstracting from it. He described this process as "being like building with Lego - start with the finished object - take it apart then re-build it - it will look similar but not exactly the same".To my surprise, I found that I had more in common with his approach than I had expected. In discussion with the audience, he talked of shadows in art as having ambiguity, transience - similar to the feelings I have been trying to capture in my photographs of shadows. I had not previously grasped the significance of layers but in many of my images, that could be what gives them the impression of texture. I felt comfortable with his explanations of abstraction, a concept I have had difficulty fully understanding previously. He is clearly happy now using a hybrid of digital photography and traditional printing, feeding contemporary technology into long established analogue processes. He is going to be in Greece for the next couple of months but has offered to let some of us visit his studio to share his technical knowledge. Having never seen photo-etching in practice or intaglio prints being made, I still have some difficulty in understanding exactly how it works and this is now on my list to do over the summer. I am sure that the learning curve for developing his printmaking skills was much steeper and longer than it took him to get what he needed from digital photography but I am still interested in printing digital negatives on acetate for use with historical U-V light based photographic processes and his advice on file preparation and printing technique could be invaluable.His final comment on his acceptance of photography as a tool for image making was to concede that "the mobile phone has become the sketch-book of the 21st century".The images used to illustrate this post were captured on my mobile phone camera.Schaefer JP (1999) 'Visualisation: The Art of Seeing a Photograph' In: Ansel Adams Guide - Basic Techniques of Photography Book (1); Revised edition, Boston-New York-London, Little, Brown and Company, pp 131-134.

Don McCullin at Tate Britain

The other 'blockbuster' exhibition of photography currently showing in London, is a very substantial retrospective at Tate Britain of the work of Don McCullin, the first photographer to have been given this accolade. Built in 1892 (as the National Gallery of British Art), in contrast to the brutalist concrete of the South Bank, this is a more refined traditional Victorian art gallery with a classical portico entrance and a central dome. The layout of the exhibition also followed relatively traditional lines; exhibition quality monochrome silver gelatin prints (all printed by McCullin in his own darkroom), window mounted in plain black frames, evenly spaced as single images or in small groups and centered at eye level around the walls of eight substantial rooms. The photographs were presented in roughly chronological order, grouped geographically starting with his earliest images of gang members in east London in the late 1950's and moving on to images of conflict zones and famines in Berlin, Cyprus, the Middle East, Vietnam and Cambodia, Sudan, Biafra as well as those showing the effects of de-industrialisation, social deprivation, poverty and homelessness in London and Northern England. The captions were mostly simple place names but two or three images in each room had more detailed explanations, describing McCullin's own insights about the situations he found himself in.I already knew his work well from several of his books and having written an essay about his photography in Year 1 of the FdA course. There were no particular surprises on offer but the volume, range and power of the photographs was as impressive as anticipated, to the point of becoming almost overwhelming. These subject matter of these images is dark, moving, poignant, even shocking but the manifest empathy of the photographer for the individuals affected, the victims of these tragedies and his desire to ensure that their stories are told, totally dispels any notion of sensationalisation or exploitation. This impression is confirmed by Colin Jacobsen in his article about the exhibition in the British Journal of Photography, who also quotes Harold Evans, McCullin's former editor at The Sunday Times "He cared about the victims, the collateral damage" and "He couldn't express it in words, but he expressed it in his photography".Although the gallery was busy, the experience of being able to examine close up, the quality in the detail of these prints, from negatives exposed in often unimaginably challenging circumstances, made the journey worthwhile. This was particularly true of a group of his later photographs presented in the final room of the exhibition, some landscape images made near his home on the Somerset Levels.

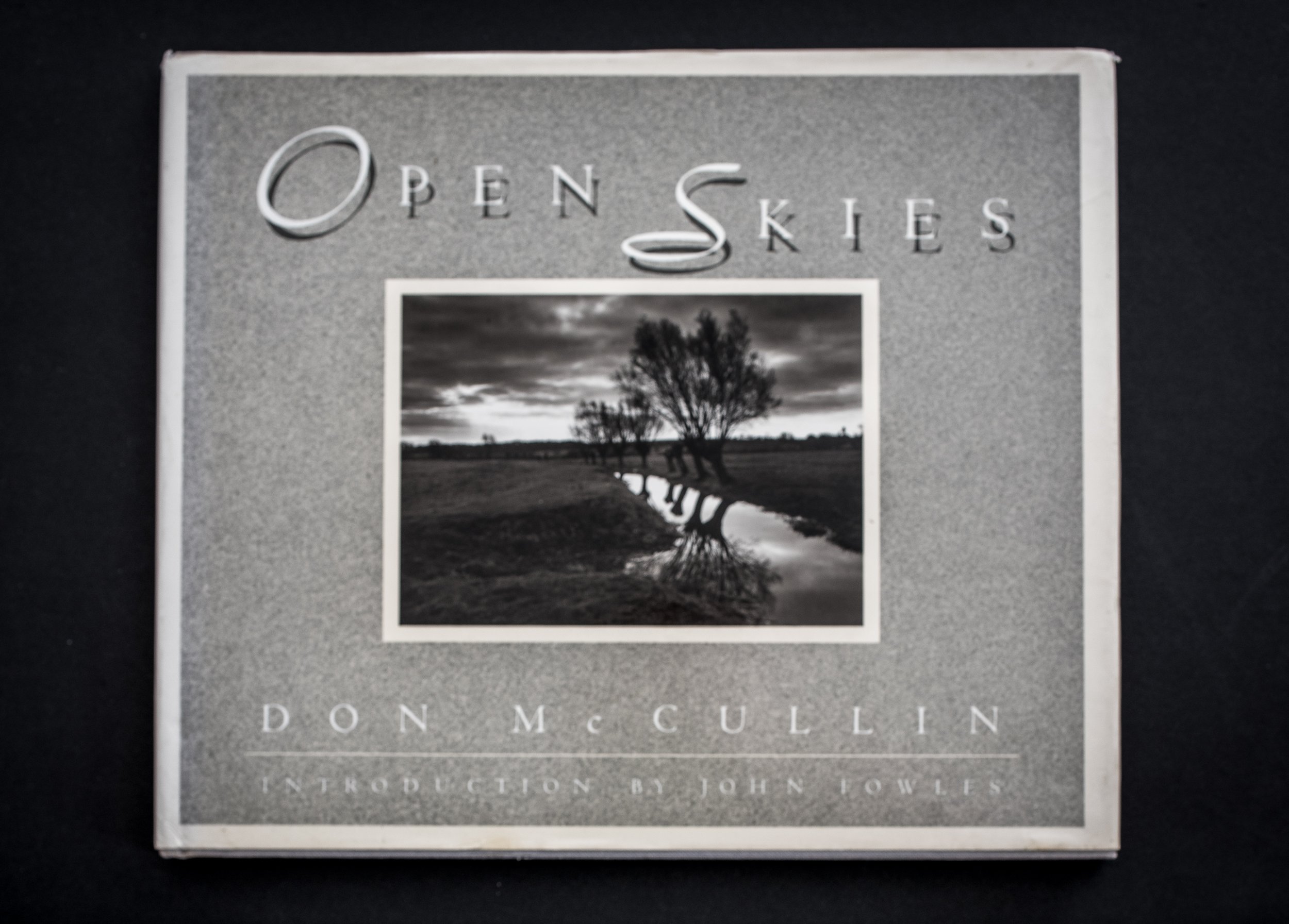

The other 'blockbuster' exhibition of photography currently showing in London, is a very substantial retrospective at Tate Britain of the work of Don McCullin, the first photographer to have been given this accolade. Built in 1892 (as the National Gallery of British Art), in contrast to the brutalist concrete of the South Bank, this is a more refined traditional Victorian art gallery with a classical portico entrance and a central dome. The layout of the exhibition also followed relatively traditional lines; exhibition quality monochrome silver gelatin prints (all printed by McCullin in his own darkroom), window mounted in plain black frames, evenly spaced as single images or in small groups and centered at eye level around the walls of eight substantial rooms. The photographs were presented in roughly chronological order, grouped geographically starting with his earliest images of gang members in east London in the late 1950's and moving on to images of conflict zones and famines in Berlin, Cyprus, the Middle East, Vietnam and Cambodia, Sudan, Biafra as well as those showing the effects of de-industrialisation, social deprivation, poverty and homelessness in London and Northern England. The captions were mostly simple place names but two or three images in each room had more detailed explanations, describing McCullin's own insights about the situations he found himself in.I already knew his work well from several of his books and having written an essay about his photography in Year 1 of the FdA course. There were no particular surprises on offer but the volume, range and power of the photographs was as impressive as anticipated, to the point of becoming almost overwhelming. These subject matter of these images is dark, moving, poignant, even shocking but the manifest empathy of the photographer for the individuals affected, the victims of these tragedies and his desire to ensure that their stories are told, totally dispels any notion of sensationalisation or exploitation. This impression is confirmed by Colin Jacobsen in his article about the exhibition in the British Journal of Photography, who also quotes Harold Evans, McCullin's former editor at The Sunday Times "He cared about the victims, the collateral damage" and "He couldn't express it in words, but he expressed it in his photography".Although the gallery was busy, the experience of being able to examine close up, the quality in the detail of these prints, from negatives exposed in often unimaginably challenging circumstances, made the journey worthwhile. This was particularly true of a group of his later photographs presented in the final room of the exhibition, some landscape images made near his home on the Somerset Levels. I have a second hand copy from America of his book 'Open Skies' published in 1989, which includes these photographs and have previously felt that they were so dark that they had been over-printed, blocking up the details in the shadow areas. Having now seen these photographs 'in the flesh', the detail in the shadows has been retained, the quality is superb and I can appreciate that the problem in the book is down to the reproduction of the images, emphasising the value in being able to get to see the original prints. In his introduction to the book, John Fowles speculates that the darkness of these images is a reflection of McCullin's 'state of mind' following his years of covering human tragedies all around the world, along with the tragedies of his own personal life.Thirty years further down the line and now aged 83, McCullin commented on this in a recent television documentary for BBC Four, confirming that as he has got older, he feels the need to make his prints darker, yet his mood now seems lighter and what was most apparent was his humility and that he still cares passionately about people, regardless of their background but especially the less fortunate among us.https://www.tate.org.uk/what's-on/tate-britain/exhibition/don-mccullinJacobsen, C., "Endframe, Don McCullin': British Journal of Photography, Issue 7882, p 98, April 2019.McCullin, D., 'Open Skies': Harmony Books, New York, 1989. (Originally published in Great Britain by Jonathon Cope).https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m0002dv0/don-mccullin-looking-for-england, Accessed on 10/4/2019

I have a second hand copy from America of his book 'Open Skies' published in 1989, which includes these photographs and have previously felt that they were so dark that they had been over-printed, blocking up the details in the shadow areas. Having now seen these photographs 'in the flesh', the detail in the shadows has been retained, the quality is superb and I can appreciate that the problem in the book is down to the reproduction of the images, emphasising the value in being able to get to see the original prints. In his introduction to the book, John Fowles speculates that the darkness of these images is a reflection of McCullin's 'state of mind' following his years of covering human tragedies all around the world, along with the tragedies of his own personal life.Thirty years further down the line and now aged 83, McCullin commented on this in a recent television documentary for BBC Four, confirming that as he has got older, he feels the need to make his prints darker, yet his mood now seems lighter and what was most apparent was his humility and that he still cares passionately about people, regardless of their background but especially the less fortunate among us.https://www.tate.org.uk/what's-on/tate-britain/exhibition/don-mccullinJacobsen, C., "Endframe, Don McCullin': British Journal of Photography, Issue 7882, p 98, April 2019.McCullin, D., 'Open Skies': Harmony Books, New York, 1989. (Originally published in Great Britain by Jonathon Cope).https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m0002dv0/don-mccullin-looking-for-england, Accessed on 10/4/2019

All I know is what's on the internet (2)

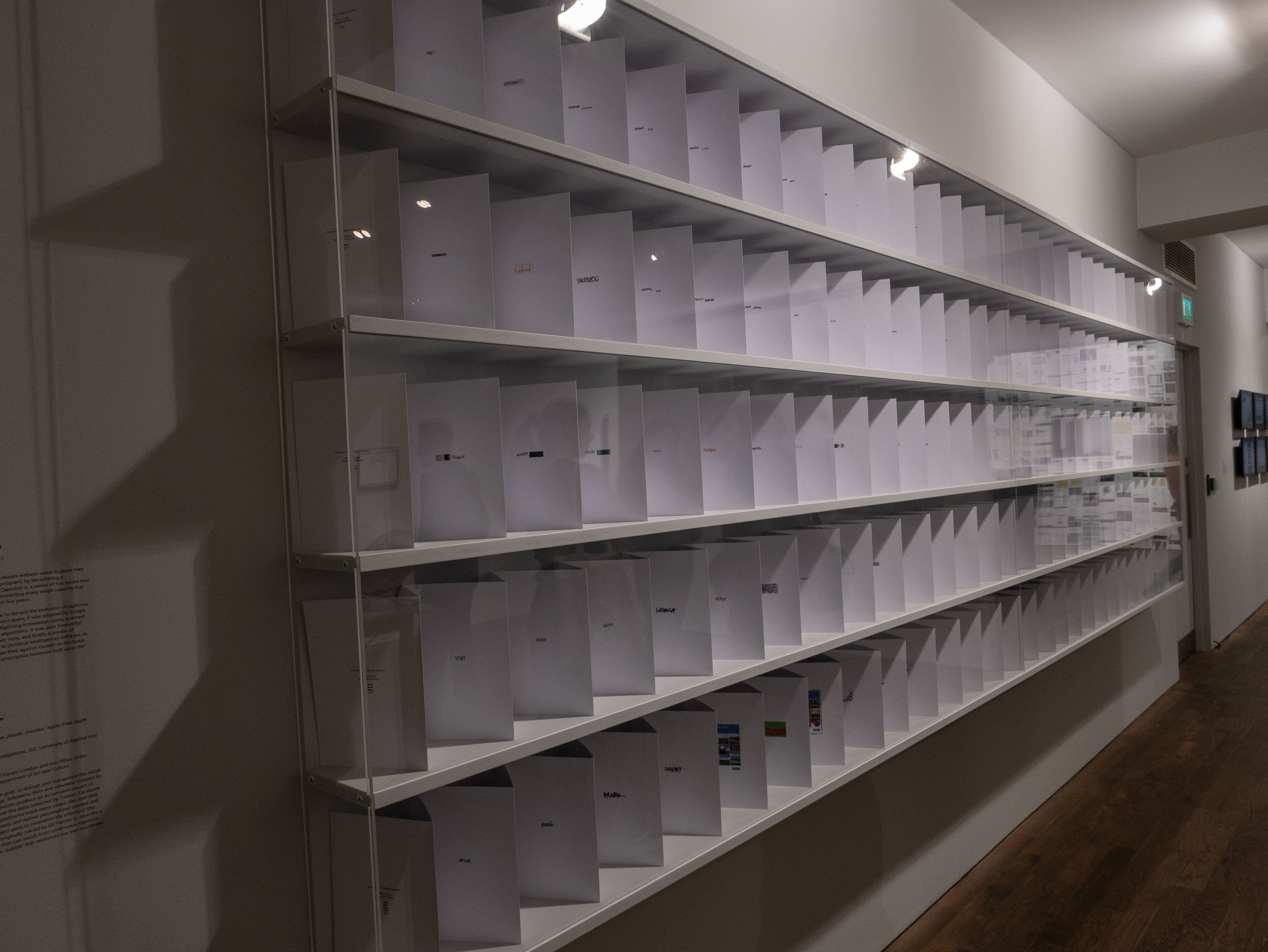

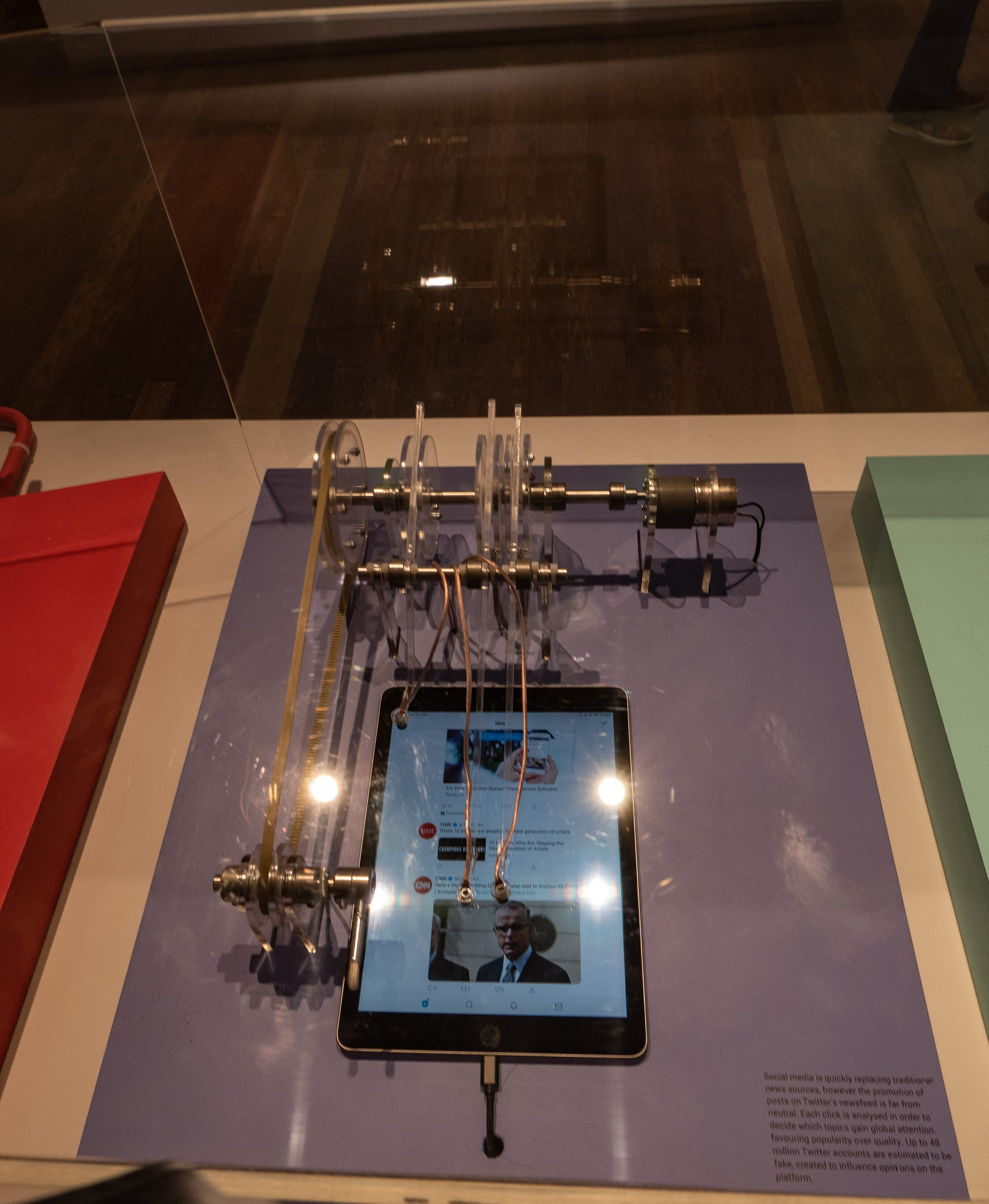

When down in London in February, I re-visited this exhibition in the Photographers Gallery just before it finished. I had spent relatively little time with the exhibits on my first visit (I had gone to the gallery primarily to see Roman Vishniac's photographs) and was anxious that I was perhaps missing the point of some of the work. The various contributors were all presenting images or artefacts from their ongoing research projects making it very relevant to this module but they were all concentrating on negative aspects of internet culture and I had struggled to find any positive messages. I felt that the issues highlighted were all important, the cynicism of the hardware manufacturers and social media platforms, the blatant deceptions perpetrated by individual and corporate users and even governments and the levels of exploitation of their workforce, potentially affecting any one of us.

My second visit confirmed this impression and although there were several examples of novel ways of exhibiting work, and some interesting videos by groups experimenting with off grid lifestyles, there was nothing about the benefits of the digital imaging media which many currently enjoy. I initially felt that this was a missed opportunity to explore the democratisation of opportunities to use photography creatively, resulting from the ease of use and access to sophisticated technologies and sources of information but this would have needed a much larger platform and was clearly not the intention of the curators.

My second visit confirmed this impression and although there were several examples of novel ways of exhibiting work, and some interesting videos by groups experimenting with off grid lifestyles, there was nothing about the benefits of the digital imaging media which many currently enjoy. I initially felt that this was a missed opportunity to explore the democratisation of opportunities to use photography creatively, resulting from the ease of use and access to sophisticated technologies and sources of information but this would have needed a much larger platform and was clearly not the intention of the curators.

For photographers, the issues which give rise to imminent concern, online financial fraud, plagiarism or repeated recycling of cliched ideas, the rapid turnover of vast numbers of increasingly homogeneous imagery and the built in obsolescence of expensive digital hardware and software (with the failure of manufacturers to provide continuing support) are all well known but were not specifically addressed by the exhibition. Good research often leads to more questions than answers and this exhibition highlighted several new areas of concern, especially in relation to the practices of the large multi-national companies providing our online services but without offering any immediate solutions. All digital photographs of the exhibits used to illustrate this post captured in situ at the Photographers Gallery, London by the author.Featured Image: Photograph of the exhibit - 'The driver and the cameras' (Google street view camera operators), Emilio Vavarelli 2012.Further information about the exhibitors is available from: www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibition/all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internet

For photographers, the issues which give rise to imminent concern, online financial fraud, plagiarism or repeated recycling of cliched ideas, the rapid turnover of vast numbers of increasingly homogeneous imagery and the built in obsolescence of expensive digital hardware and software (with the failure of manufacturers to provide continuing support) are all well known but were not specifically addressed by the exhibition. Good research often leads to more questions than answers and this exhibition highlighted several new areas of concern, especially in relation to the practices of the large multi-national companies providing our online services but without offering any immediate solutions. All digital photographs of the exhibits used to illustrate this post captured in situ at the Photographers Gallery, London by the author.Featured Image: Photograph of the exhibit - 'The driver and the cameras' (Google street view camera operators), Emilio Vavarelli 2012.Further information about the exhibitors is available from: www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibition/all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internet

Return to Manchester : Martin Parr

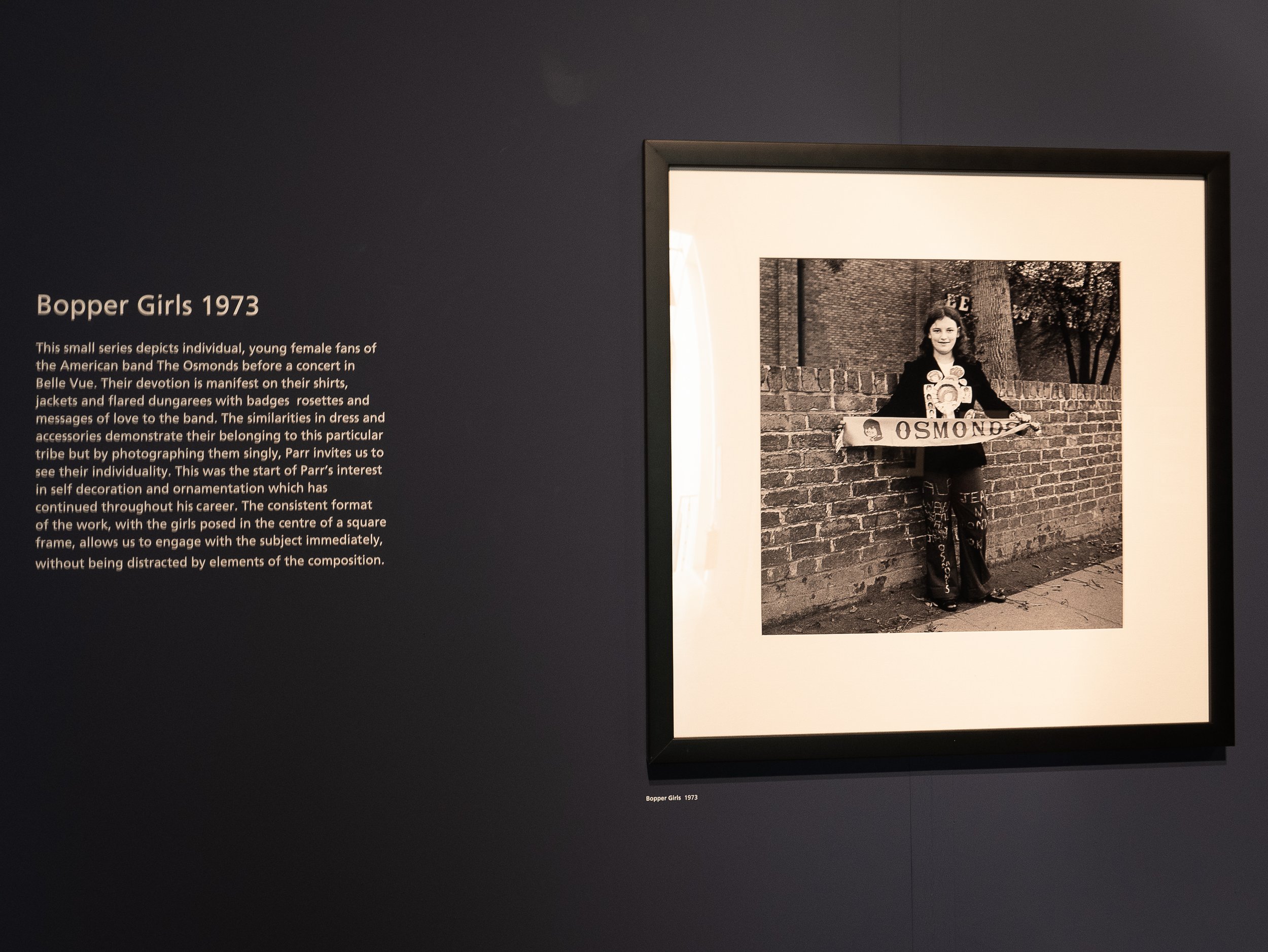

This exhibition currently showing at Manchester Art Gallery focuses on Martin Parr's long term engagement with the people of the city and the surrounding industrial towns of the North West, which form the region of Greater Manchester. From his first student projects in 1970, over a period of nearly fifty years, he has returned regularly and his work now constitutes a substantial documentary record of the changes in the fabric of city's buildings along with its' cultural and social development from an industrial region to modern twenty-first century metropolis.By concentrating on the lives of the inhabitants he has recorded the effects of on one hand, the social deprivation resulting from de-industrialization and on the other, the gentrification of parts of the city, which closely mirrors the changes seen in other major UK cities. The thread which runs through these projects is his ability to capture the warmth and resilience of the people he photographed along the way, especially those from the working class areas. His early black and white photographs are still resonant of the times they covered. His series from the psychiatric hospital in Prestwich are especially poignant and his medium format photographs of girl 'teenyboppers’ manage to capture a sense of the personalities of the teenagers as well as the period detail of their clothing. The layout of the exhibition seamlessly follows his switch to working in colour in the early 1980’s, making the change appear to fit logically with the ways in which that period is now usually remembered (colour in television screens, magazines and newspaper supplements, at that time becoming the norm). The colours recorded in the details of people's everyday lives; shop windows, home decor, clothing, are particularly resonant of the times.

His early black and white photographs are still resonant of the times they covered. His series from the psychiatric hospital in Prestwich are especially poignant and his medium format photographs of girl 'teenyboppers’ manage to capture a sense of the personalities of the teenagers as well as the period detail of their clothing. The layout of the exhibition seamlessly follows his switch to working in colour in the early 1980’s, making the change appear to fit logically with the ways in which that period is now usually remembered (colour in television screens, magazines and newspaper supplements, at that time becoming the norm). The colours recorded in the details of people's everyday lives; shop windows, home decor, clothing, are particularly resonant of the times. More than a few contemporary photographers (including myself) have commented that they find his more recent digital colour images less easy to relate to, which seems difficult to comprehend given that his working methods and subject matter have not significantly changed and the colours and clarity of detail in the images are if anything truer to life. Perhaps now we already know his work so well that there are now simply fewer surprises or the use of digital capture somehow lacks the resonance we felt looking at the earlier work with analogue materials. Alternatively could it be that these images are too close to what we see around us and in the media every day - does familiarity breed contempt? Perhaps if we are still here, we might respond to them more positively in another twenty years time.http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/martin-parr/

More than a few contemporary photographers (including myself) have commented that they find his more recent digital colour images less easy to relate to, which seems difficult to comprehend given that his working methods and subject matter have not significantly changed and the colours and clarity of detail in the images are if anything truer to life. Perhaps now we already know his work so well that there are now simply fewer surprises or the use of digital capture somehow lacks the resonance we felt looking at the earlier work with analogue materials. Alternatively could it be that these images are too close to what we see around us and in the media every day - does familiarity breed contempt? Perhaps if we are still here, we might respond to them more positively in another twenty years time.http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/martin-parr/

Diane Arbus : 'in the beginning'

The Hayward gallery in the South Bank Centre in London is currently showing an exhibition of original monochrome analogue photographs made by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) between 1956 and 1962. Although from the age of eighteen, she had worked in fashion and advertising alongside her husband, the actor and photographer Allan Arbus, she did not embark on the work for which she is now well known, until she was in her early thirties. At that time, while she was studying with Lisette Model, she began to make photographs of people she met in the street in and around the less affluent areas of New York City and Coney Island. These images, best described as her early formative work, were made using 35mm film cameras printed at 6 x 9 inches by Arbus herself and two thirds of them have not been shown previously in the U.K.

The Hayward gallery in the South Bank Centre in London is currently showing an exhibition of original monochrome analogue photographs made by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) between 1956 and 1962. Although from the age of eighteen, she had worked in fashion and advertising alongside her husband, the actor and photographer Allan Arbus, she did not embark on the work for which she is now well known, until she was in her early thirties. At that time, while she was studying with Lisette Model, she began to make photographs of people she met in the street in and around the less affluent areas of New York City and Coney Island. These images, best described as her early formative work, were made using 35mm film cameras printed at 6 x 9 inches by Arbus herself and two thirds of them have not been shown previously in the U.K. As perhaps expected, the quality of the images does not equate with that of her much better known later medium format photographs but the gallery did not permit photography in this exhibition so I have no available examples to show. There was a small area, separate from the main body of the exhibition, showing a folio of ten of her medium format prints (printed at 20 x 20 inches) and the difference in quality was clearly evident. That said, the earlier photographs explored a wider range of subject matter, informal portraits, street photography, people in fairgrounds or at the beach, cinema and theatre audiences and people through restaurant windows. A few images appeared to be screen shots on television sets and there were some found still lives on wet pavements. Several of the prints showed pronounced grain effects and in some (especially the low-light images) the focus was quite soft but this imparted a degree of freshness or rawness to the work which appeared less planned or staged than her photographs from the mid 1960's onwards. This would be an important collection for anyone studying Diane Arbus, demonstrating the early stages of the evolution of her working practice.

As perhaps expected, the quality of the images does not equate with that of her much better known later medium format photographs but the gallery did not permit photography in this exhibition so I have no available examples to show. There was a small area, separate from the main body of the exhibition, showing a folio of ten of her medium format prints (printed at 20 x 20 inches) and the difference in quality was clearly evident. That said, the earlier photographs explored a wider range of subject matter, informal portraits, street photography, people in fairgrounds or at the beach, cinema and theatre audiences and people through restaurant windows. A few images appeared to be screen shots on television sets and there were some found still lives on wet pavements. Several of the prints showed pronounced grain effects and in some (especially the low-light images) the focus was quite soft but this imparted a degree of freshness or rawness to the work which appeared less planned or staged than her photographs from the mid 1960's onwards. This would be an important collection for anyone studying Diane Arbus, demonstrating the early stages of the evolution of her working practice. For my own research, perhaps the most striking aspect of this exhibition was the way in which the work was presented (I made the one photograph shown above before I noticed the small 'No Photography' sign on the plain wall on the right of the image). There were no photographs on the perimeter walls of the space, which were painted in a deep rich matt navy blue (almost black) colour. As shown, the main gallery contained about forty evenly spaced free standing pillars painted in matt white with one photograph only on each long side. The prints were traditionally window mounted in dark metallic pewter like frames and the immediate impressions created by the design were of light airiness and opulently high quality minimalist precision, with a hushed atmosphere indicating genuine reverence for the work being presented.Diane Arbus tragically took her own life in 1971 and I think she would have been pleased with this exhibition but although the gallery has gone to great lengths (and expense) to create an impressive setting for the photographs, I felt to an extent that the design almost overwhelmed the actual images, perhaps reinforcing my impression that this was not her best work. In the information at the gallery entrance, the curators explained that the work had not been arranged in any chronological order and that viewers should feel free to find their own route around the gallery at their own pace. This worked well while the gallery was initially quiet but it filled up quite quickly and I was conscious of people around me moving from pillar to pillar in different directions at different speeds to the extent that I felt under pressure to move on, to avoid holding them up. Although many were individually fascinating, the disparate selection of images were placed surprisingly randomly with no obvious attempt to formally sequence them. This could of course have been an attempt to subliminally re-create the feel of the circumstances in which they were created but overall it felt more like a triumph of style over substance.https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/diane-arbus-beginninghttps://www.biography.com/people/diane-arbus-9187461

For my own research, perhaps the most striking aspect of this exhibition was the way in which the work was presented (I made the one photograph shown above before I noticed the small 'No Photography' sign on the plain wall on the right of the image). There were no photographs on the perimeter walls of the space, which were painted in a deep rich matt navy blue (almost black) colour. As shown, the main gallery contained about forty evenly spaced free standing pillars painted in matt white with one photograph only on each long side. The prints were traditionally window mounted in dark metallic pewter like frames and the immediate impressions created by the design were of light airiness and opulently high quality minimalist precision, with a hushed atmosphere indicating genuine reverence for the work being presented.Diane Arbus tragically took her own life in 1971 and I think she would have been pleased with this exhibition but although the gallery has gone to great lengths (and expense) to create an impressive setting for the photographs, I felt to an extent that the design almost overwhelmed the actual images, perhaps reinforcing my impression that this was not her best work. In the information at the gallery entrance, the curators explained that the work had not been arranged in any chronological order and that viewers should feel free to find their own route around the gallery at their own pace. This worked well while the gallery was initially quiet but it filled up quite quickly and I was conscious of people around me moving from pillar to pillar in different directions at different speeds to the extent that I felt under pressure to move on, to avoid holding them up. Although many were individually fascinating, the disparate selection of images were placed surprisingly randomly with no obvious attempt to formally sequence them. This could of course have been an attempt to subliminally re-create the feel of the circumstances in which they were created but overall it felt more like a triumph of style over substance.https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/diane-arbus-beginninghttps://www.biography.com/people/diane-arbus-9187461