"The World of Roger Ballen" is an exhibition of the work of one of the most innovative contemporary photographers, showing currently and until July 2020 at the Halle St Pierre in Montmartre, Paris. The gallery itself is a light airy space on two levels, the upper galleries being accessed from a balcony overlooking the ground floor cafe and bookshop. It specialises in showing 'Art Brut' or outsider art, makes it particularly appropriate for this work. The current exhibition uses the upper floor for a fairly standard formal presentation of a generous selection Ballen's photographs as large framed prints, with some of his drawings directly on the walls and some of the props used in his work. Downstairs, the gallery contains recreations of several of the spaces he has photographed in the form of a series of vignettes, again using the photographer's own props, models, artworks and even a life sized model of himself with his Rolleiflex on a rotating pedestal. There was also a separate projection room showing a sequence of short films of the places and people he has worked with.

"The World of Roger Ballen" is an exhibition of the work of one of the most innovative contemporary photographers, showing currently and until July 2020 at the Halle St Pierre in Montmartre, Paris. The gallery itself is a light airy space on two levels, the upper galleries being accessed from a balcony overlooking the ground floor cafe and bookshop. It specialises in showing 'Art Brut' or outsider art, makes it particularly appropriate for this work. The current exhibition uses the upper floor for a fairly standard formal presentation of a generous selection Ballen's photographs as large framed prints, with some of his drawings directly on the walls and some of the props used in his work. Downstairs, the gallery contains recreations of several of the spaces he has photographed in the form of a series of vignettes, again using the photographer's own props, models, artworks and even a life sized model of himself with his Rolleiflex on a rotating pedestal. There was also a separate projection room showing a sequence of short films of the places and people he has worked with.

As can be seen above, the places and people he has photographed would perhaps best be described as being on the very fringes of society and the images are imaginative, darkly humorous, intriguing and sometimes challenging. The films shown at the gallery are also available on his website and perhaps give a better feel for the atmosphere in which his work is created. Ballen has recently been interviewed for the October edition of the British Journal of Photography by Michael Grieve and an interview with him at Paris Photo is also available on their websitewww.rogerballen.comhttps://www.hallesaintpierre.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/DP-HSP_Roger-Ballen.pdfGrieve M. 'The World according to Roger Ballen', British Journal of Photography, Issue No.7888, pp 38-49, October 2019.

As can be seen above, the places and people he has photographed would perhaps best be described as being on the very fringes of society and the images are imaginative, darkly humorous, intriguing and sometimes challenging. The films shown at the gallery are also available on his website and perhaps give a better feel for the atmosphere in which his work is created. Ballen has recently been interviewed for the October edition of the British Journal of Photography by Michael Grieve and an interview with him at Paris Photo is also available on their websitewww.rogerballen.comhttps://www.hallesaintpierre.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/DP-HSP_Roger-Ballen.pdfGrieve M. 'The World according to Roger Ballen', British Journal of Photography, Issue No.7888, pp 38-49, October 2019.

A Very Very Very Dark Matter

My son bought us tickets for this new play at the Bridge Theatre on London’s South Bank, because he knew that I had enjoyed the work of the playwright Martin McDonagh (who wrote the film screenplays for ‘In Bruges’ and ‘Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri’). On that basis but knowing little else about it in advance, we expected a story with dark humour, irreverence, subversion and unpredictable plot twists – and it had all of these, at least in parts. The first and third acts starred Johnetta Eulua’Mae Ackles as a Congolese dwarf imprisoned in a locked cage, suspended from the ceiling of an attic in mid-19th century Copenhagen, in which she was forced to write stories for Hans Christian Andersen (played as a pompous overbearing buffoon by Jim Broadbent), who then published them in his own name and who had also cut off her right foot to stop her escaping. The story was explained by an offstage narrator, voiced by Tom Waits (presumably pre-recorded) and centred on the contradictory and ambiguous aspects of the personality of the prolific and highly successful writer of children’s stories, as well as some less well known novels and travelogues. Other issues explored included disability/deformity, racism, colonialism, genocide (by the Belgian Army in the Congo), authorship/plagiarism, repressed but ambiguous sexuality, obsessive but unrequited passion, time-travelling ghosts and a haunted accordion with a concealed machine gun.While this all sounds like a surrealist fantasy (which is what I think it was), it is evident that the author has undertaken a considerable amount of research in preparation for writing the story. Several biographers have referred to Andersen’s unusual personality, based on contemporary accounts and from his own diaries. He had a difficult childhood in which he was abused by strictly religious adoptive parents. He was celibate because of his religious beliefs and never married but became intensely infatuated at various times in his life with individuals of both sexes, none of whom reciprocated his feelings (Lepage, 2006). The second act, set around Charles Dickens’ dining room table, was based on a visit by Andersen to the author’s home in which he bored and irritated Dickens and his family by outstaying his welcome by several weeks. He died in unusual circumstances after falling out of his bed and a small skeleton with the right foot missing, was found in his attic after his death.Press reviews of the play have been at best mixed, with several commenting that the plot was overcomplicated, disjointed, deliberately shocking to the point of being over-sensationalised and some found the humour gratuitously offensive (Online reviews, 2018). It seemed as if the play had been written in a hurry or possibly originally envisaged as a film and I thought the story did at times stray close to the line between an effective piece of ‘theatre of the absurd’ and flippant or frivolous silliness. For me however this was offset greatly by the dark shadowy lighting and the atmospheric set design of the attic by Anna Fleischle, with Gothic arched ceilings, scattered dolls and children’s toys and hanging puppets. The effect of this was to create a uniquely surreal visual experience and although the script could have been more cohesive, it was a very different and enjoyable theatrical spectacle, a dark stranger than fiction fairytale.ReferencesLepage R, 2006. ‘The perverse side of Hans Christian Andersen’, Guardian newspaper article Accessed on 30/11/2016 at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/jan/18/theatre.classicsOnline reviews, 2018. Accessed on 30/11/2018 at: https://www.whatsonstage.com/london-theatre/news/very-dark-matter-review-round-up-critics-bridge_47880.htmlImagesFeatured banner image copied from the Bridge Theatre website, Accessed on 5/12/2018 at: https://bridgetheatre.co.uk/whats-on/a-very-very-very-dark-matterSet design photograph copied from the Jewish Chronicle website, Accessed on 5/12/2018 at: https://www.thejc.com/culture/theatre/theatre-review-a-very-very-very-dark-matter-1.472020

The effect of this was to create a uniquely surreal visual experience and although the script could have been more cohesive, it was a very different and enjoyable theatrical spectacle, a dark stranger than fiction fairytale.ReferencesLepage R, 2006. ‘The perverse side of Hans Christian Andersen’, Guardian newspaper article Accessed on 30/11/2016 at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/jan/18/theatre.classicsOnline reviews, 2018. Accessed on 30/11/2018 at: https://www.whatsonstage.com/london-theatre/news/very-dark-matter-review-round-up-critics-bridge_47880.htmlImagesFeatured banner image copied from the Bridge Theatre website, Accessed on 5/12/2018 at: https://bridgetheatre.co.uk/whats-on/a-very-very-very-dark-matterSet design photograph copied from the Jewish Chronicle website, Accessed on 5/12/2018 at: https://www.thejc.com/culture/theatre/theatre-review-a-very-very-very-dark-matter-1.472020

Viviane Sassen

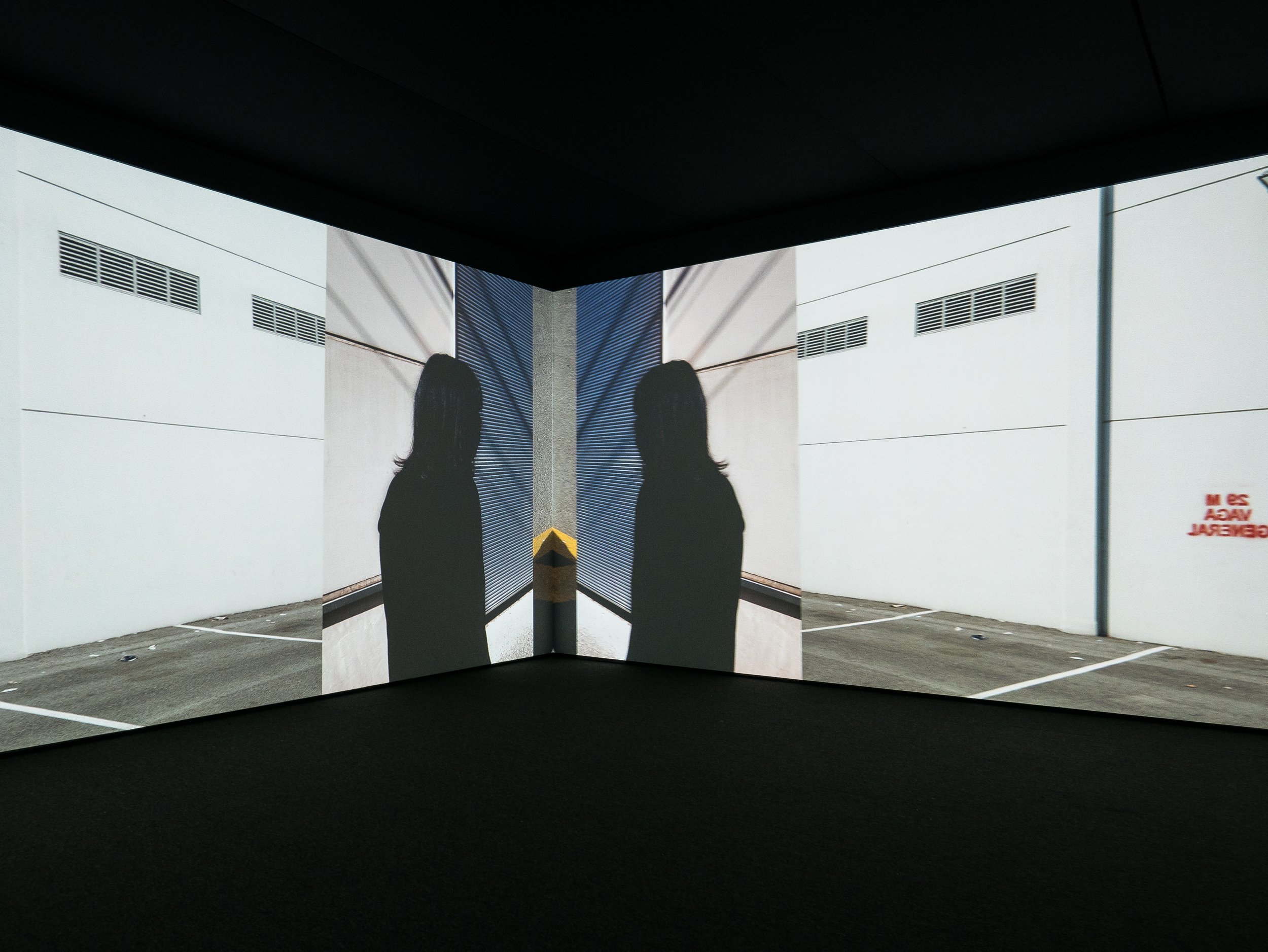

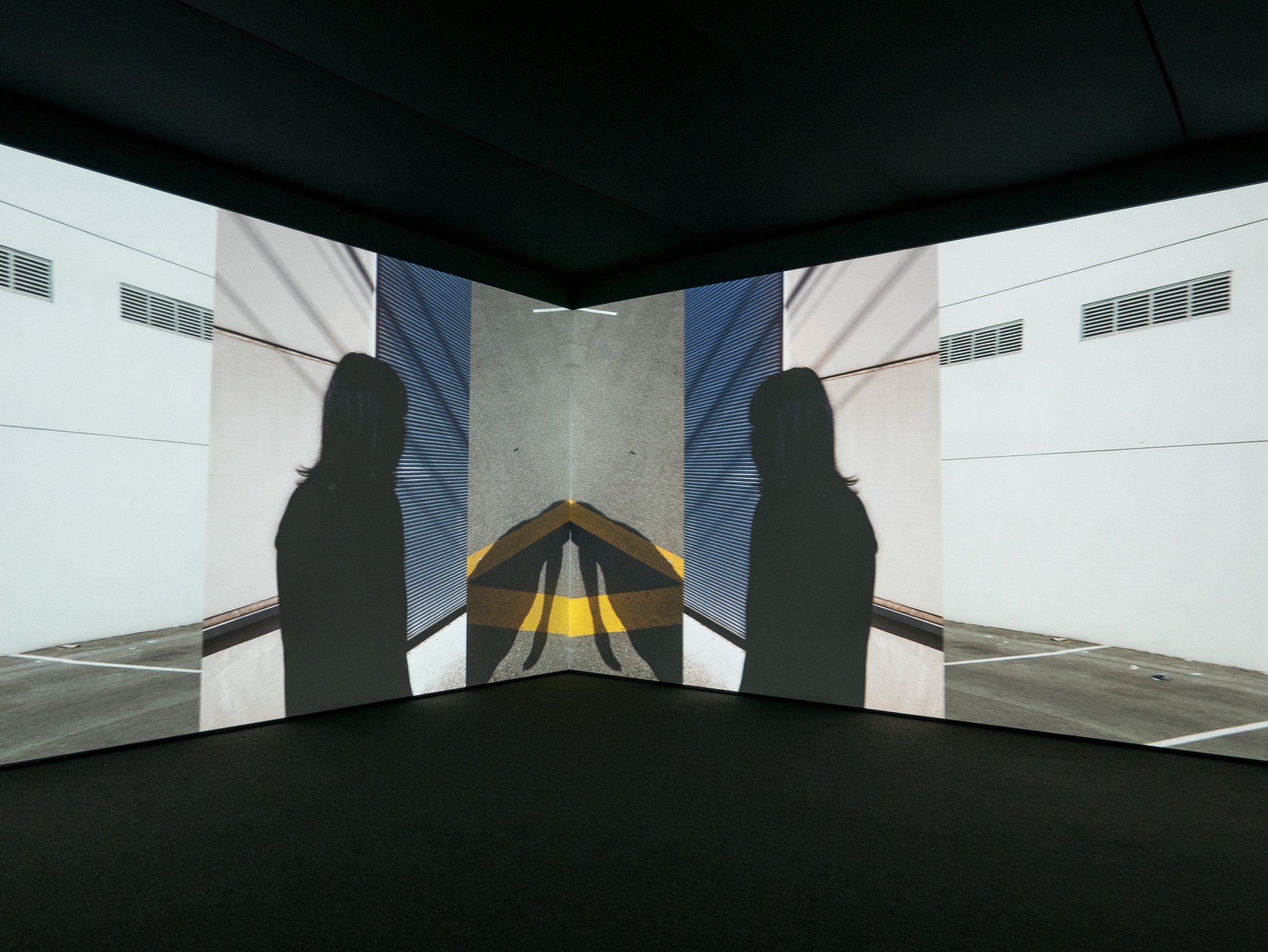

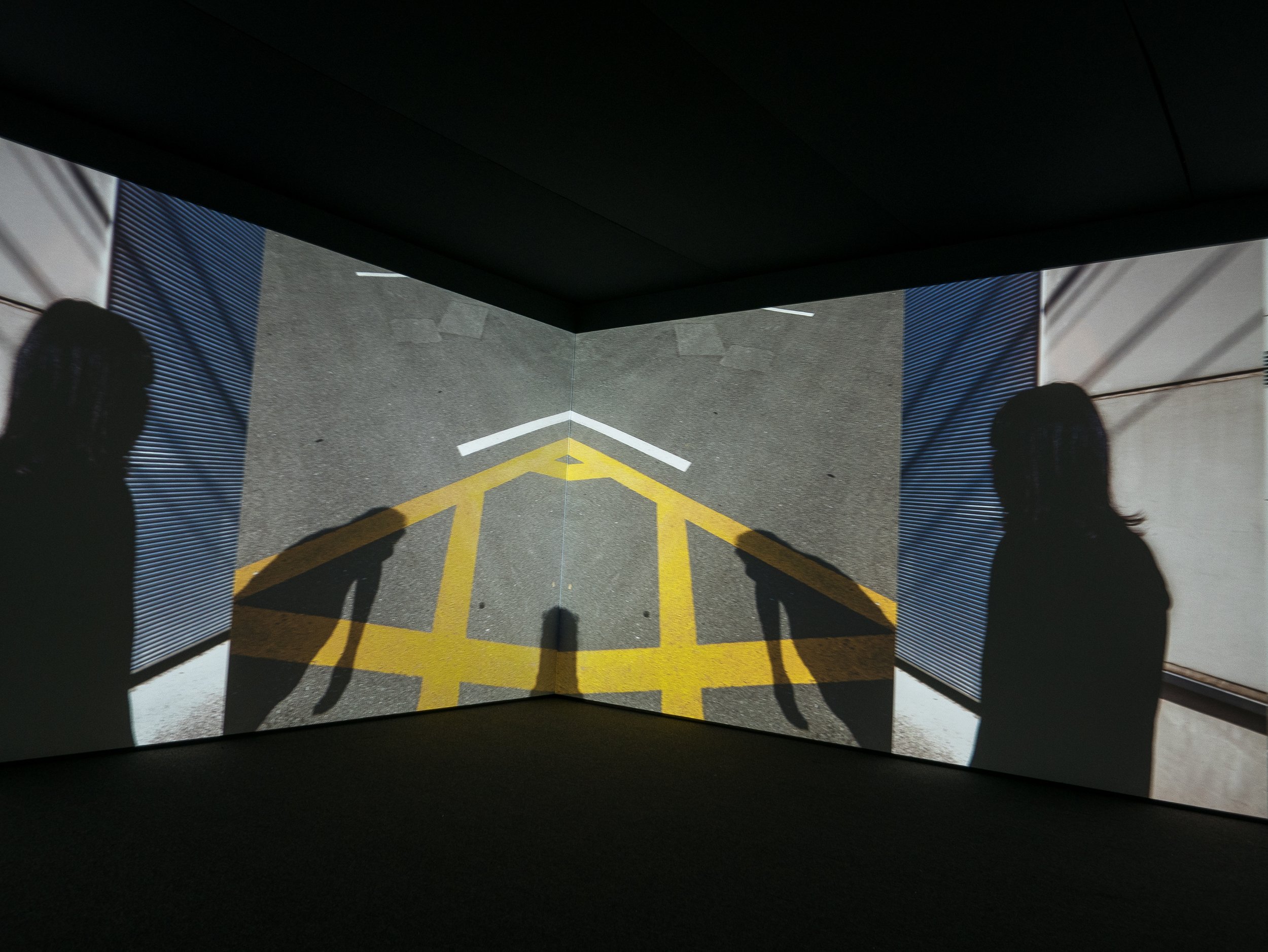

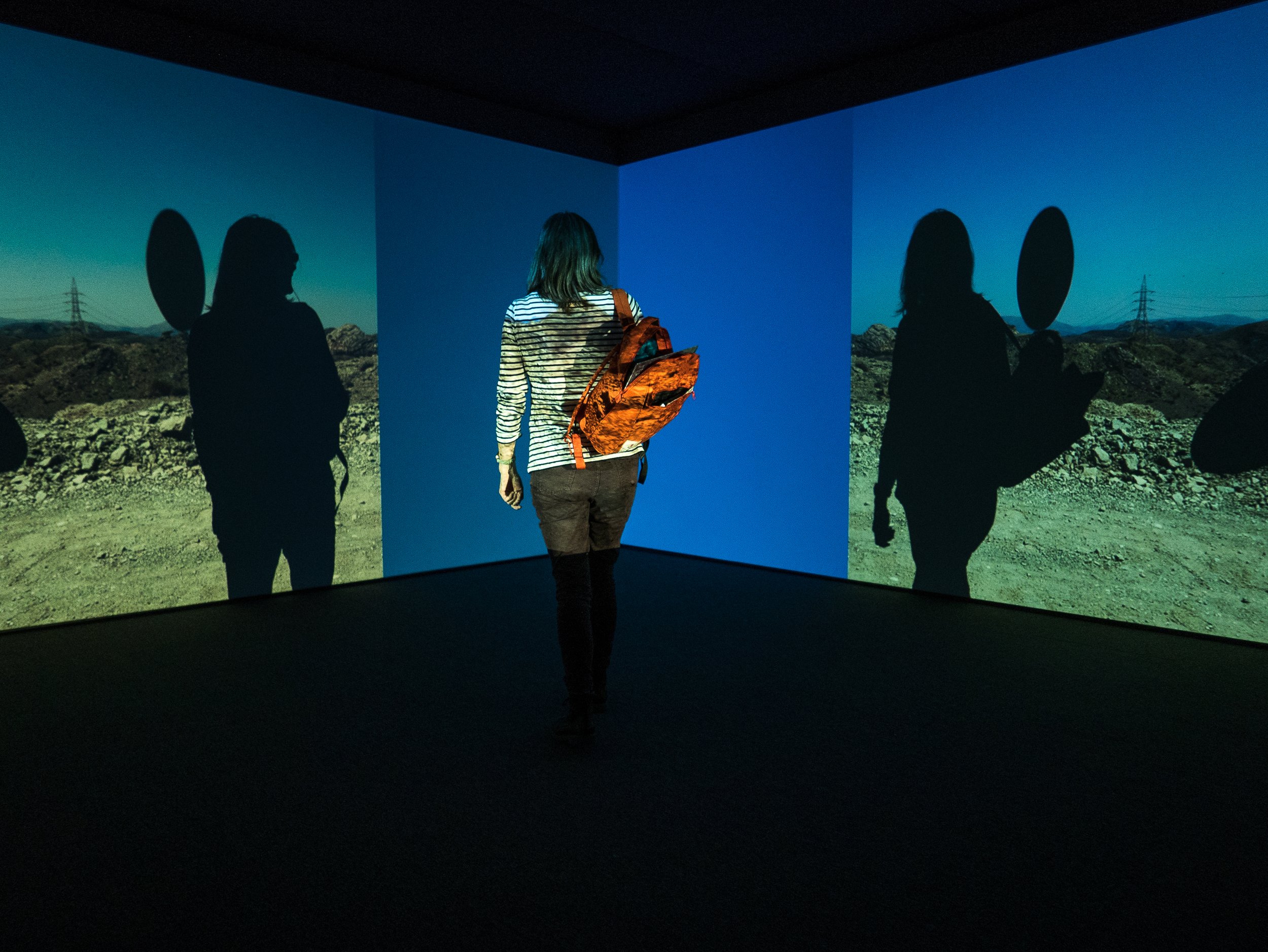

Hepworth Gallery Wakefield, October 2018Also showing contemporaneously with the “Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain” exhibition at the Hepworth was an exhibition of the work of the Dutch fine art photographer Viviane Sassen and for several reasons, the placement of her work in the adjacent gallery was an inspired curatorial decision. Born in Amsterdam in 1972, Vivienne Sassen initially chose to study fashion and design in Arnhem in 1990 which led to a brief period working as a fashion model while also moving to the other side of the camera to study photography in Utrecht from 1992 until 1996, then back to Arnhem where she completed a Masters degree in fine art in 1998. She has a very successful career as a fashion photographer and although she still lives and works in Amsterdam, she spent several years in her early childhood in East Africa, which subsequently proved to be a major influence on her life and her work, much of which has been made on return visits to Africa as an adult. In an interview for the exhibition catalogue she has explained that although she is now exhibiting mainly her fine art photography, she still derives much of her energy from fashion which has become an outlet for her exuberance. “In fashion I can express my extroverted side; in my more personal work, the introverted side” (Ammerlaan, 2018). In addition to the parallels with the career of Lee Miller, these more personal images often explore the ideas which are commonly associated with Surrealism – dreams, childhood memories, chance associations, eroticism and death. Her work also exploits some of the techniques favoured by the surrealist artists including the use of collage, mixed media, unexpected juxtapositions, disjointed bodies, incongruous colour combinations, mirrors with reflected or refracted light, shadows and on occasions even solarisation. While her books and previous exhibitions of her work have each been based on specific individual projects, on this occasion, working in close collaboration with the curators, the wall mounted photographs have been presented as small groups of images, each consisting of photographs chosen from several different bodies of her work over the last ten years. Through unexpected juxtapositions these individual ‘image poems’ are held together by the themes and motifs which have been features running through her work over this time.The most striking first impression of the images is her use of colour, bright lighting and graphic shapes, drawing on her experience in fashion photography as evident in the quality of her photographic technique, compositional design skills, her ability to work effectively with models and in the presentation of the images . The Hepworth is a gallery designed with large bright open spaces to accommodate the large three-dimensional sculptural works with which it is more often associated. This however also makes it an ideal setting for showcasing her work by giving the groups of wall mounted photographs plenty of ‘room to breathe’. In addition, the middle of the gallery space was occupied by a large white cube which formed the centrepiece (literally) of the exhibition. The exterior of this cube made it appear simply as additional wall space for several further groups of photographs but the interior, accessed by a light-trap door in one corner, was a large square projection room, the innovative design of which is difficult to describe clearly in words alone (hence the attached images).The two walls opposite the entrance to the space were filled by large white projection screens and the images projected onto them consisted of a rolling montage of continually moving high contrast colourful still photographs with graphic shapes, shadows and silhouettes of people, animals or trees and foliage, against backgrounds of desert landscapes, blue skies, urban facades or tarmac roads with lane bright markings. The images projected on the left hand wall flowed across the screen from right to left, while those on the right hand screen were mirror images of the same photographs simultaneously moving from left to right. The resulting appearance this created in that corner of the space was a continuously moving ‘Rorschach effect’ metamorphosis of abstract shapes, patterns and colours. The other two walls in the space were large mirrors, each with a small central aperture for the two projector beams, these mirrors reflecting in focus the continually moving projected images on the opposite walls. The effect for the viewer was further enhanced when on moving into the room they crossed the projector beams, resulting in their own shadows interacting with the shadows and silhouettes in the photographs, such that they effectively became part of the evolving images. (I did say it was difficult to explain in words). The degree of technical precision required to achieve the synchronisation of this installation is itself a major achievement and to combine this with the thought-provoking imagery it produced can only be described as an artistic triumph.My initial interest in visiting this exhibition, in relation to my own work, was stimulated by the little I already knew about her work with shadows on desert sand to create abstract compositions, using mirrors and coloured gels. The complex themes explored in her figurative imagery show that this is the work of a mature, engaged artist and the ground-breaking centrepiece projection installation produced a contemporary surreal experience, which lifted this exhibition to an entirely different level. Although I had previously only associated surrealism with the movement active in the period between the two world wars and into the 1950's, I am now more aware of its lasting influence and continuing relevance to the present time.

Ammerlaan R. ‘A Shy Exhibitionist: the Loss and Longing of Viviane Sassen, Photographer and Artist’, In: Hot Mirror Ed. Holtz C., Prestel Verlag, Munich London New York, 2018.https://www.vivianesassen.com/news/https://www.wefolk.com/artists/vivianne-sassen/information

Ammerlaan R. ‘A Shy Exhibitionist: the Loss and Longing of Viviane Sassen, Photographer and Artist’, In: Hot Mirror Ed. Holtz C., Prestel Verlag, Munich London New York, 2018.https://www.vivianesassen.com/news/https://www.wefolk.com/artists/vivianne-sassen/information

Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain

Hepworth Gallery Wakefield, October 2018In photography circles the American born photographer Lee Miller (1907-1977) is best known for her work in fashion and war photography and perhaps for Man Ray’s photographs of her while she was his studio assistant/model/muse in Paris from 1929 to 1932. This wide-ranging exhibition explores her less well known role in the evolution and promotion of Surrealist art in Britain, from the 1930’s through to the early 1960’s, using her photographs of many of the active participants in the movement, their work and their exhibitions as well as the photographic work she exhibited alongside them. The works exhibited are a diverse collection of photographs by Lee Miller and artworks by the surrealist artists she knew and collaborated with, in the form of paintings, sculptures, some photographs, mixed media collages, posters, magazines, pamphlets, exhibition catalogues and promotional materials.Lee Miller’s work on show included some formal portraits from her studio in Paris with examples of the solarisation technique she developed along with Man Ray, informal portraits of surrealist artists in various settings, often when they visited the home she set up in England with Roland Penrose, some landscape work from the Mediterranean and Egypt, installation shots of surrealist exhibitions in London, some of her fashion work with Vogue during World War II, some of her wartime photographs on assignment in France, Germany and the holocaust concentration camps as well as the famous photograph of her in the bathtub in Hitler’s apartment in Berlin (by David E Scherman). The surrealist artworks exhibited had all been part of previous exhibitions in England in the years leading up to, during and after the war and included work by Miller herself and (among others) Roland Penrose (her second husband), Man Ray, Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington, Joan Miró, Paul Nash, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dali, Giorgio de Chirico, Eileen Agar, E.L.T. Mesens, Henry Moore, René Magritte and several other less well known English artists.The exhibition was organised in a series of rooms, with each of these covering separate periods in her career. They were arranged chronologically starting with her time in Paris, moving onto her moving to England, then covering the wartime years and finally, some of her work as a curator in the 1950’s and 1960’s. The overall feel of the exhibition was something akin to that of a history lesson and in that respect, it worked very well. The Lee Miller photographs from Paris, the informal portraits of the artists and the wartime photographs were all powerful images. The examples of studio portraits printed using ‘solarisation’ to create reversal of some of the tones in the images were especially effective and I felt there could have been more of these on show (Man Ray had taken the credit for inventing this effect but Miller later claimed that she had discovered it by chance - when developing a print she transiently switched on the room light after a mouse ran over her foot in his darkroom). While there were several very striking images among the work of the other artists on show, quite a few of them were surprisingly disappointing. The lighting in these galleries was kept quite low, presumably for conservation reasons and many of the paintings, drawings and posters seem to have faded and were quite drab in appearance. They would undoubtedly have been seen as strange, new, sensational, or even shocking when they were first shown but the ability of these surrealist images to astonish appears to have diminished with familiarity and with the passing of time*.Thinking back, a few weeks after visiting the exhibition, I can recall two images which I felt were particularly memorable. The first of these was a small exquisitely delicate painting by Yves Tanguy entitled ‘Imaginary Landscape’ (1933), a panoramic letterbox sized still life presented as a desert scene with several small unusual looking domestic objects and their shadows, similar in appearance to some of Salvador Dali’s more dramatic and fantastical desert landscapes but infinitely more subtle. The second was a pair of photographs by Lee Miller called ‘Untitled (Severed Breast from Radical Surgery in a Place Setting 1 and 2)’ (Paris, 1929). These are photographs of a surgical mastectomy specimen on a plate at a dinner table, with a knife and fork on either side. The first of these shows the skin ellipse and nipple/areola complex (showing evidence of retraction by the cancer) facing upwards and is clearly recognisable as a breast but the second has been placed with the skin facing downwards which in a black and white photograph makes the specimen look like a plate of minced meat. These images conform with the recurring surrealist themes of unexpected juxtaposition of finding unusual objects in everyday settings and depictions of fragmented or distorted body parts but could also indicate that Miller was commenting on the fact that the fragmented bodies often seen in surrealist images (usually by male artists) were almost always female. I am sure this image was felt to be shocking at the time it was made and suspect most people would still be shocked by it. As a retired surgeon who specialised in treating breast cancer patients my reaction is perhaps understandably less typical – rather than shock, I simply felt uneasy, considering how the patient would have felt if she had seen these photographs and the ethical issues of patient confidentiality and respect for her dignity (and I thought I was immune to political correctness).* The gallery did not allow any photographs to be taken in this exhibition space. The featured banner image is a copy of the cover of the catalogue book written for the exhibition, copied from the Hepworth Wakefield website, accessed on 27/10/2018 at: www.hepworthwakefield.org/whats-on/lee-miller-and-surrealism-in-britain/