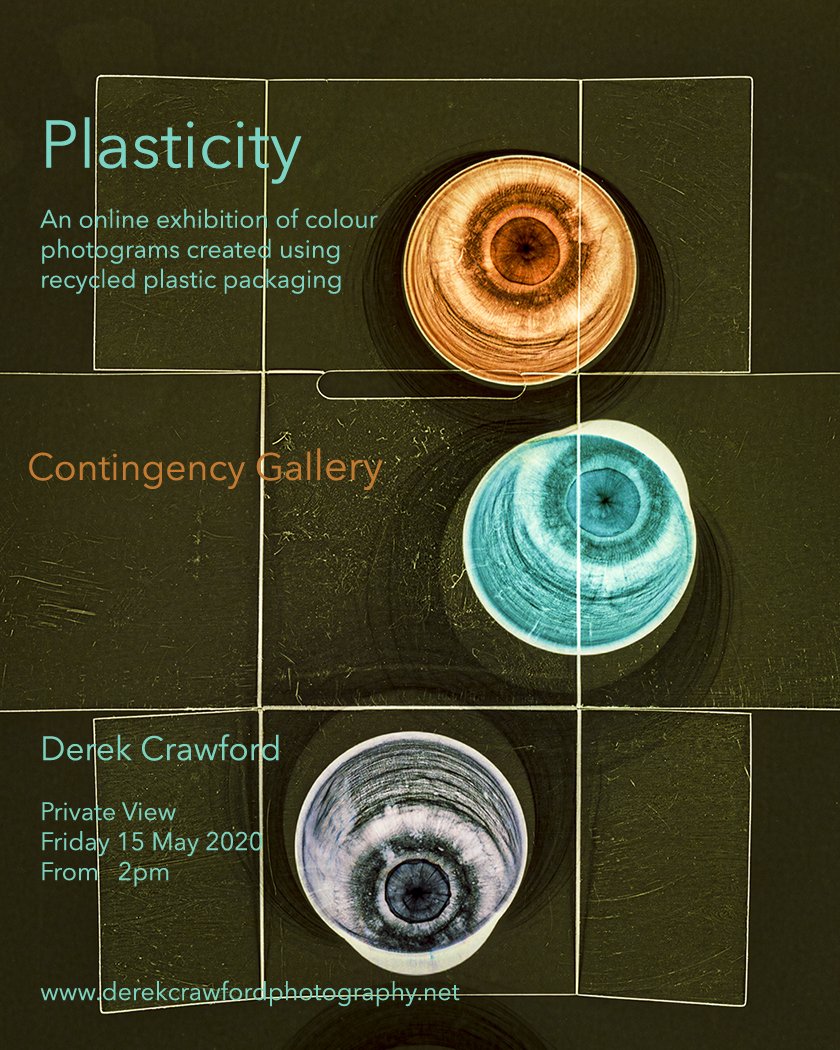

The spread of the Corona Virus epidemic in the UK in March 2019, with the ensuing government enforced social distancing measures and restrictions on movement and association, resulted in the effective lockdown of many public places including educational establishments, council buildings and galleries. This led in turn to the cancellation of our planned end of year exhibition - which would have formed the basis of the submission for our Final Major Project module to complete the requirements of my BA Degree in Photography at Coleg Llandrillo in North Wales.I found it impossible to dispel my deep conviction that a physical print format would be the most appropriate way to present the particular body of work, a series of colour photograms made using the contents of my recycle bin. To resolve this dilemma I decided to build a personal gallery space as a 1 in 12 scale maquette in which to exhibit physical prints, as originally planned. The exhibition is called PLASTICITY and can be viewed on my portfolio website at http://www.derekcrawfordphotography.net or using the direct link to a You Tube Video at youtube.com/watch?v=g-rnFbcAeXg

Garry Fabian Miller - Ingleby Gallery

The Ingleby Gallery is a small privately run gallery located since May 2018 in an A-listed former Glasite* Meeting House in the historic New Town in Edinburgh. The gallery has held and regularly shown work by the Dartmoor based photographer, Garry Fabian Miller since 2000 and their current ongoing exhibition - 'Midwinter Blaze' - is a small selection of his large scale abstract prints. Fabian Miller is a relatively unusual photographer, inasmuch that for the last 30 years he has worked without a camera, creating his images in the darkroom using only light, projected directly onto Cibachrome papers, which use a (now discontinued) direct positive dye-destruction chemical process, renowned for producing a very characteristic vivid colour pallette. The colours in his prints are created by passing the light through coloured liquids or oils in glass containers of various shapes and sizes. He stopped selling his Cibachrome original prints in 2009, retaining these now for use as his working archive (and ultimately destined for the Victoria and Albert museum collection in London). He now produces his gallery scale images in collaboration with the printer John Bodkin, using a hybrid process in which the scanned originals are processed and printed from a digital enlarger onto photosensitive colour paper, then developed and fixed chemically (Lamda 'C' prints).

Fabian Miller is a relatively unusual photographer, inasmuch that for the last 30 years he has worked without a camera, creating his images in the darkroom using only light, projected directly onto Cibachrome papers, which use a (now discontinued) direct positive dye-destruction chemical process, renowned for producing a very characteristic vivid colour pallette. The colours in his prints are created by passing the light through coloured liquids or oils in glass containers of various shapes and sizes. He stopped selling his Cibachrome original prints in 2009, retaining these now for use as his working archive (and ultimately destined for the Victoria and Albert museum collection in London). He now produces his gallery scale images in collaboration with the printer John Bodkin, using a hybrid process in which the scanned originals are processed and printed from a digital enlarger onto photosensitive colour paper, then developed and fixed chemically (Lamda 'C' prints). The main gallery in the Ingleby is a large single square room with a decorative but beautifully simple octagonal stained glass skylight at the centre of the ceiling.

The main gallery in the Ingleby is a large single square room with a decorative but beautifully simple octagonal stained glass skylight at the centre of the ceiling.  The corridor and stairs lead past the gallery offices and upstairs to a smaller more intimate second gallery, laid out like a large domestic drawing room with a period fireplace, deep comfortable couches and a large viewing table. The framed prints on the walls in this gallery are representative samples of the other artists affiliated to the Ingleby, shown as they could appear in a potential buyers home.

The corridor and stairs lead past the gallery offices and upstairs to a smaller more intimate second gallery, laid out like a large domestic drawing room with a period fireplace, deep comfortable couches and a large viewing table. The framed prints on the walls in this gallery are representative samples of the other artists affiliated to the Ingleby, shown as they could appear in a potential buyers home. The gallery was visited late on a dark winter afternoon with the gallery lighting creating reflections on the glass frames so these photographs are presented simply to give an idea of the space and the scale of the work shown. They come nowhere near to reproducing the subtle detail or the true colours of the actual prints - the gallery website makes a much better job of this. Apart from their size and the vibrant colours, the striking feature of Fabian Miller's images is the luminescent high gloss finish, re-creating the unique almost metallic looking surface finish of Cibachrome, such that on first sight, it is difficult to be certain that they are prints and not in fact light boxes.

The gallery was visited late on a dark winter afternoon with the gallery lighting creating reflections on the glass frames so these photographs are presented simply to give an idea of the space and the scale of the work shown. They come nowhere near to reproducing the subtle detail or the true colours of the actual prints - the gallery website makes a much better job of this. Apart from their size and the vibrant colours, the striking feature of Fabian Miller's images is the luminescent high gloss finish, re-creating the unique almost metallic looking surface finish of Cibachrome, such that on first sight, it is difficult to be certain that they are prints and not in fact light boxes. This exhibition finishes on 20th December 2019.www.inglebygallery.comwww.garryfabianmiller.com* According to the Ingleby Gallery website, the Glasites are a strict religious group of Scottish Protestants, who following the teachings of the Reverend John Glas, broke away from the Church of Scotland in 1732. The building was designed by Alexander Black and built in the 1830's. It was last used as a place of worship in 1989 and was in the care of the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust prior to the Ingleby Gallery moving in.

This exhibition finishes on 20th December 2019.www.inglebygallery.comwww.garryfabianmiller.com* According to the Ingleby Gallery website, the Glasites are a strict religious group of Scottish Protestants, who following the teachings of the Reverend John Glas, broke away from the Church of Scotland in 1732. The building was designed by Alexander Black and built in the 1830's. It was last used as a place of worship in 1989 and was in the care of the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust prior to the Ingleby Gallery moving in.

Royal Scottish Academy Annual Exhibition

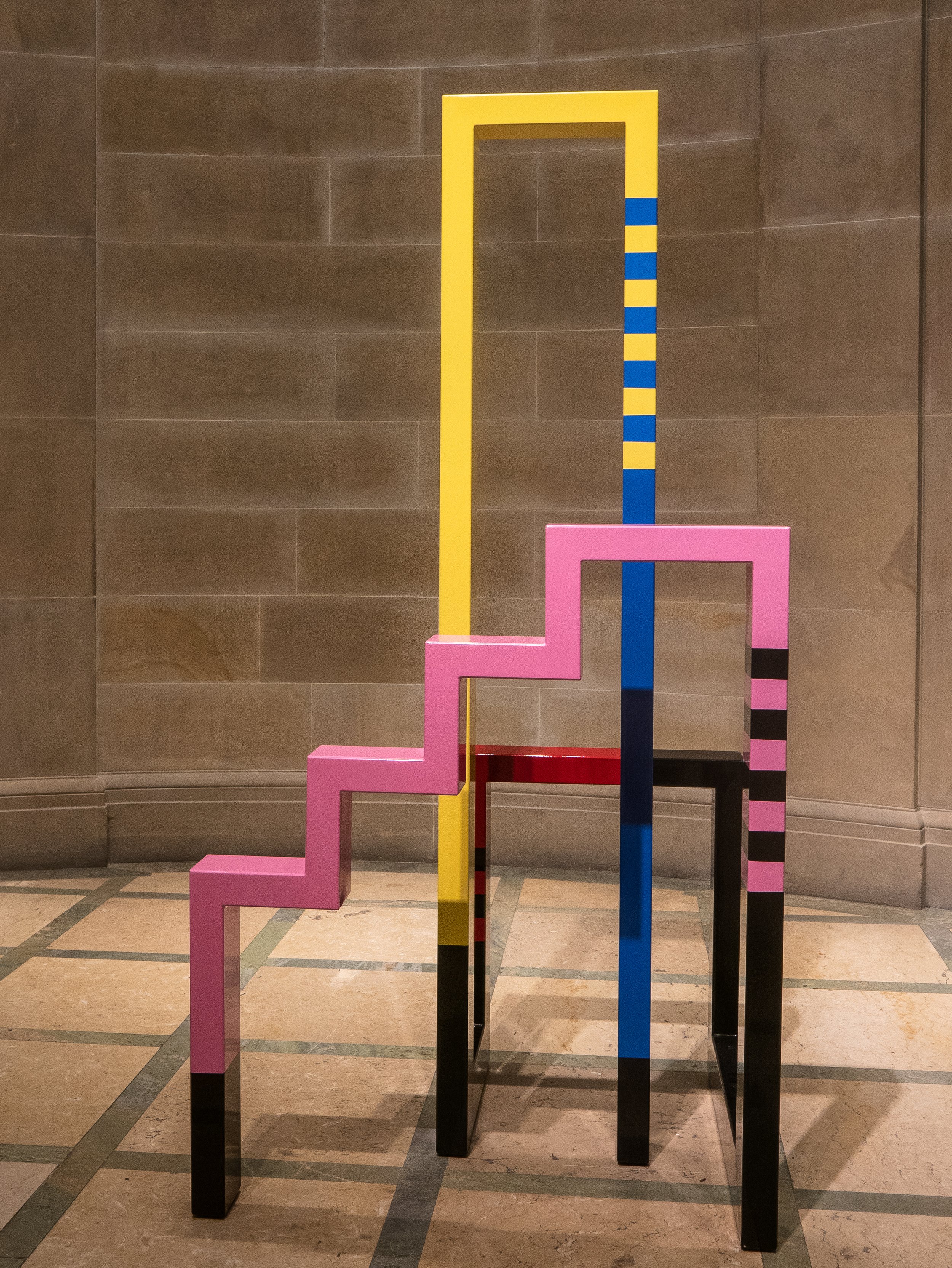

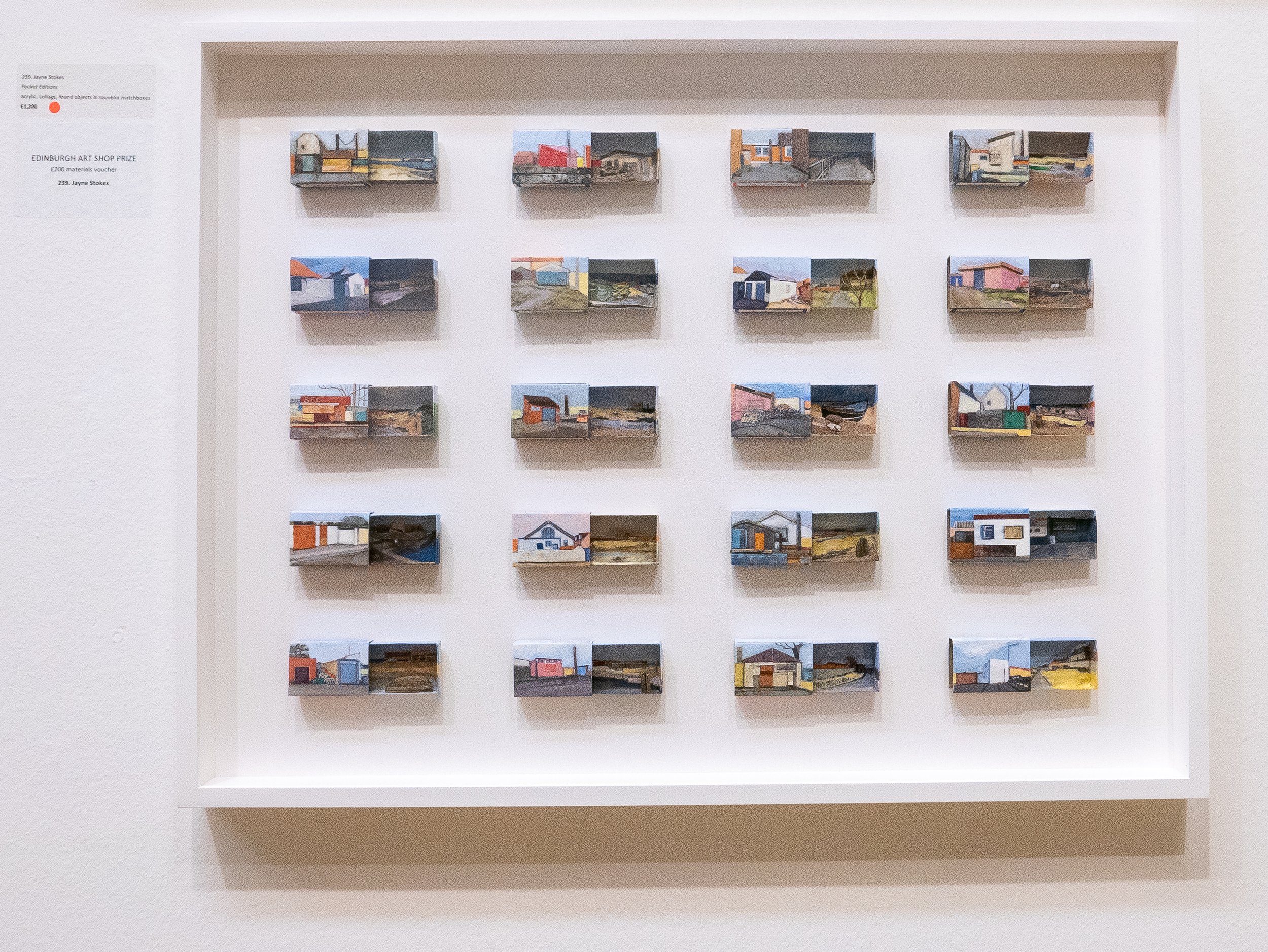

The 193rd Annual Exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, is showing currently in the National Gallery of Scotland on Princess Street, Edinburgh until 11th December, 2019. Entry is free and a generous selection of the work on show can be found on their very useful website. Most of the exhibits are paintings but there were also a reasonable number of sculptures, some installations and video art. The two rooms devoted to the architectural entries were particularly interesting.My own photographs below show some examples of just a few of the exhibits which particularly caught my eye.

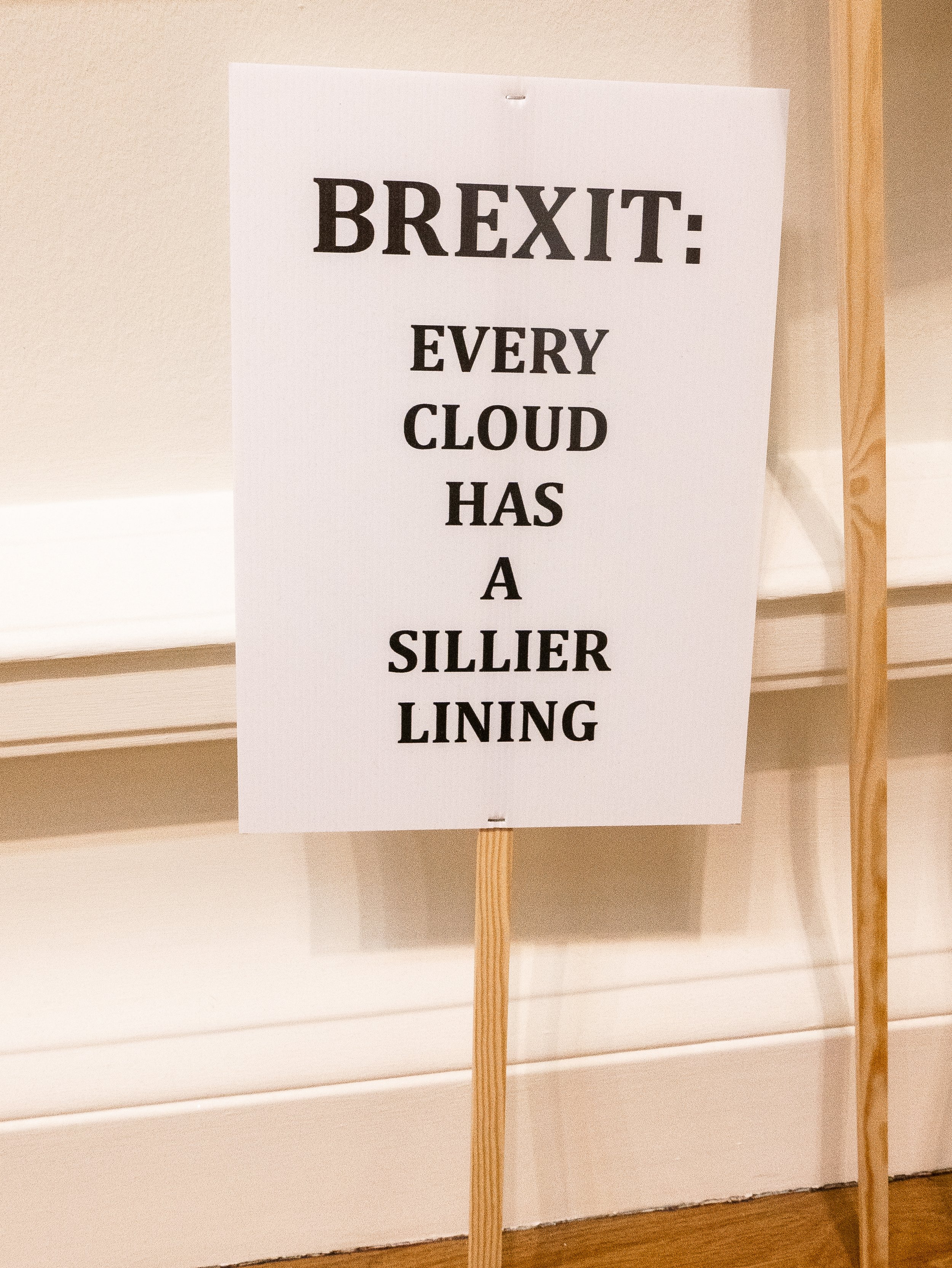

As a comment on the current state of play in UK politics, it seemed appropriate to show a closer look at the detail in this installation piece. The protester below who was photographed outside the gallery on the following morning appears to agree.

As a comment on the current state of play in UK politics, it seemed appropriate to show a closer look at the detail in this installation piece. The protester below who was photographed outside the gallery on the following morning appears to agree. https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/exhibitions/rsa-annual-exhibition-2019/

https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/exhibitions/rsa-annual-exhibition-2019/

The World of Roger Ballen

"The World of Roger Ballen" is an exhibition of the work of one of the most innovative contemporary photographers, showing currently and until July 2020 at the Halle St Pierre in Montmartre, Paris. The gallery itself is a light airy space on two levels, the upper galleries being accessed from a balcony overlooking the ground floor cafe and bookshop. It specialises in showing 'Art Brut' or outsider art, makes it particularly appropriate for this work. The current exhibition uses the upper floor for a fairly standard formal presentation of a generous selection Ballen's photographs as large framed prints, with some of his drawings directly on the walls and some of the props used in his work. Downstairs, the gallery contains recreations of several of the spaces he has photographed in the form of a series of vignettes, again using the photographer's own props, models, artworks and even a life sized model of himself with his Rolleiflex on a rotating pedestal. There was also a separate projection room showing a sequence of short films of the places and people he has worked with.

"The World of Roger Ballen" is an exhibition of the work of one of the most innovative contemporary photographers, showing currently and until July 2020 at the Halle St Pierre in Montmartre, Paris. The gallery itself is a light airy space on two levels, the upper galleries being accessed from a balcony overlooking the ground floor cafe and bookshop. It specialises in showing 'Art Brut' or outsider art, makes it particularly appropriate for this work. The current exhibition uses the upper floor for a fairly standard formal presentation of a generous selection Ballen's photographs as large framed prints, with some of his drawings directly on the walls and some of the props used in his work. Downstairs, the gallery contains recreations of several of the spaces he has photographed in the form of a series of vignettes, again using the photographer's own props, models, artworks and even a life sized model of himself with his Rolleiflex on a rotating pedestal. There was also a separate projection room showing a sequence of short films of the places and people he has worked with.

As can be seen above, the places and people he has photographed would perhaps best be described as being on the very fringes of society and the images are imaginative, darkly humorous, intriguing and sometimes challenging. The films shown at the gallery are also available on his website and perhaps give a better feel for the atmosphere in which his work is created. Ballen has recently been interviewed for the October edition of the British Journal of Photography by Michael Grieve and an interview with him at Paris Photo is also available on their websitewww.rogerballen.comhttps://www.hallesaintpierre.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/DP-HSP_Roger-Ballen.pdfGrieve M. 'The World according to Roger Ballen', British Journal of Photography, Issue No.7888, pp 38-49, October 2019.

As can be seen above, the places and people he has photographed would perhaps best be described as being on the very fringes of society and the images are imaginative, darkly humorous, intriguing and sometimes challenging. The films shown at the gallery are also available on his website and perhaps give a better feel for the atmosphere in which his work is created. Ballen has recently been interviewed for the October edition of the British Journal of Photography by Michael Grieve and an interview with him at Paris Photo is also available on their websitewww.rogerballen.comhttps://www.hallesaintpierre.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/DP-HSP_Roger-Ballen.pdfGrieve M. 'The World according to Roger Ballen', British Journal of Photography, Issue No.7888, pp 38-49, October 2019.

Paris Photo 2019

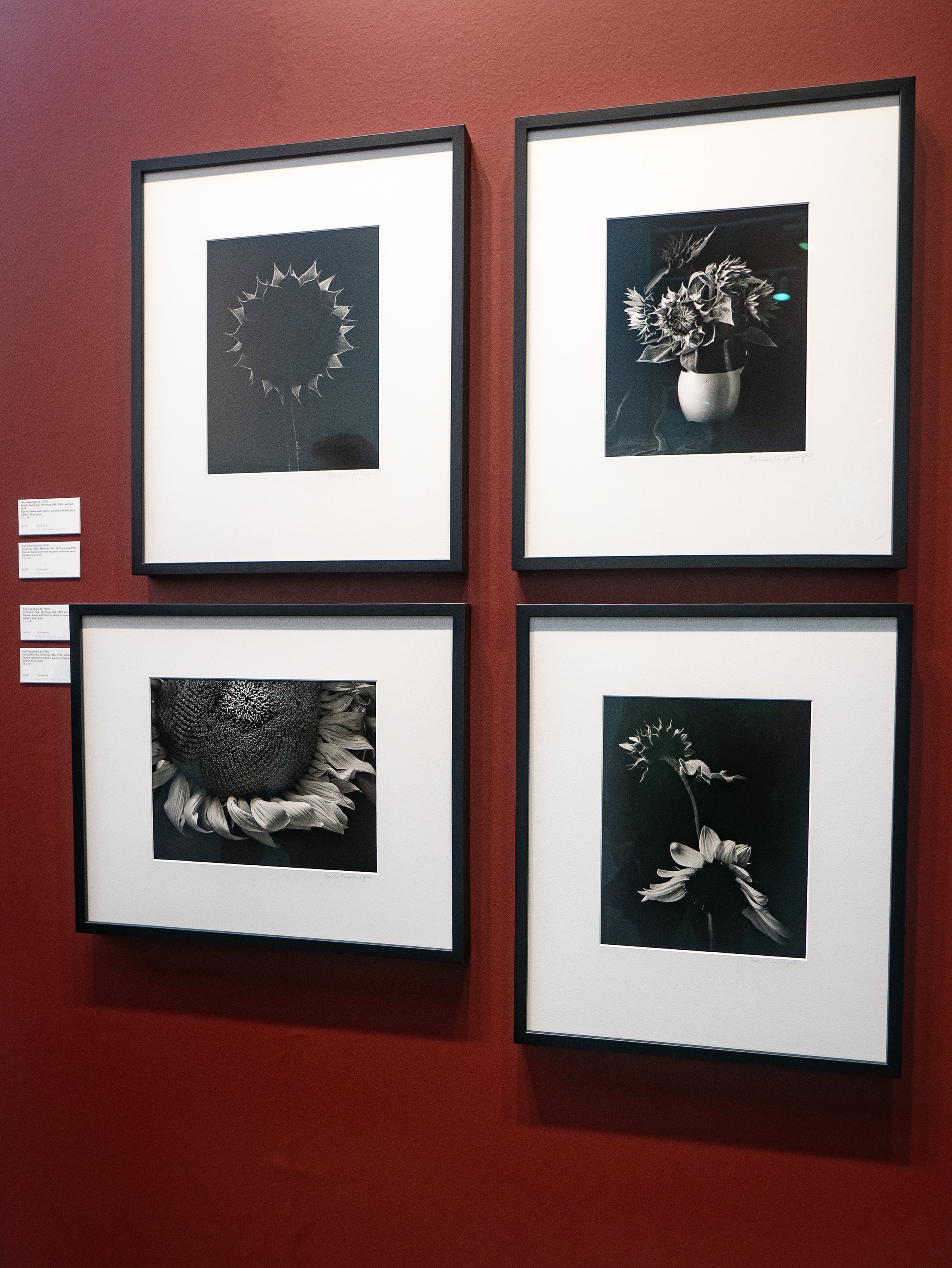

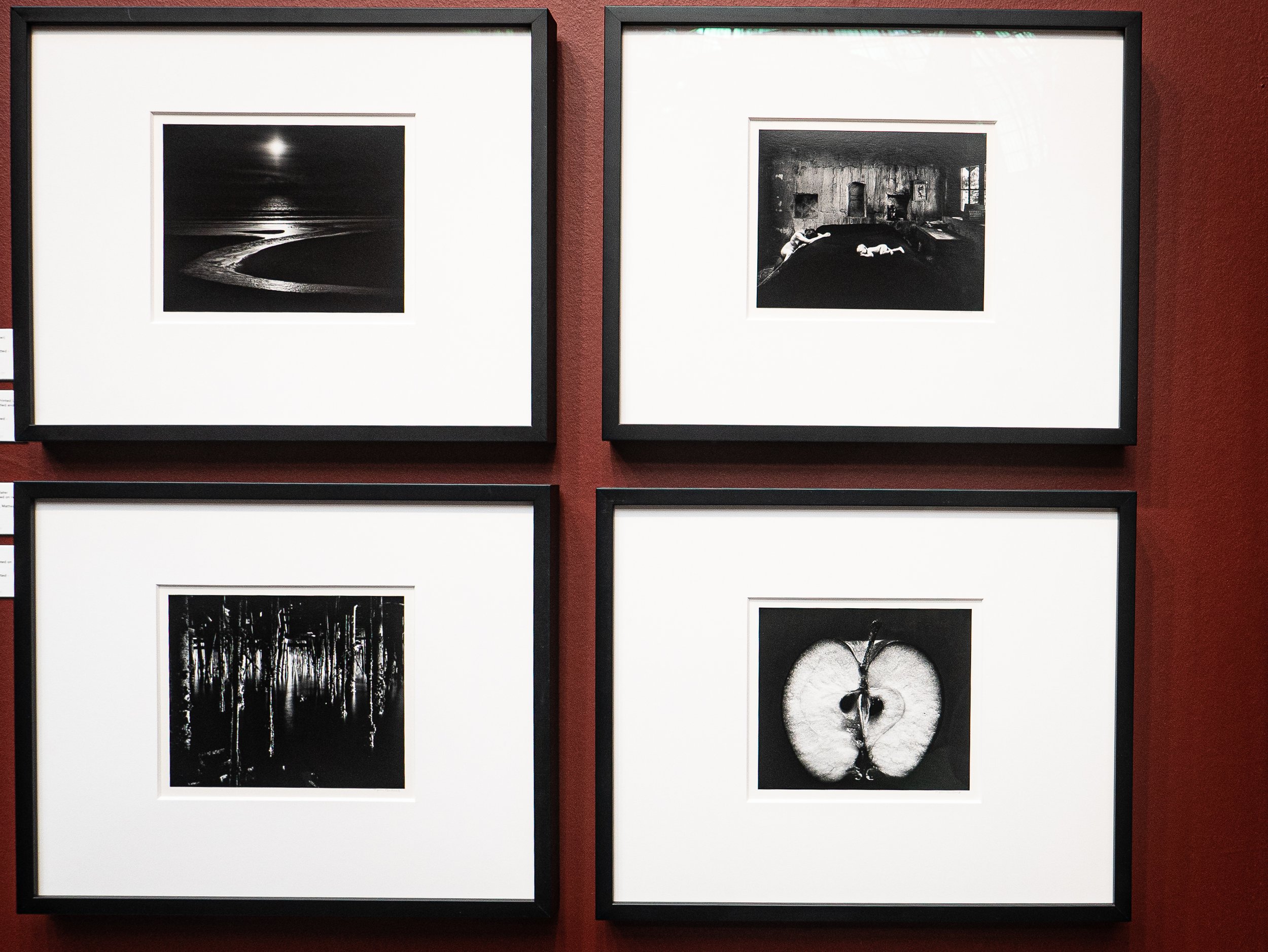

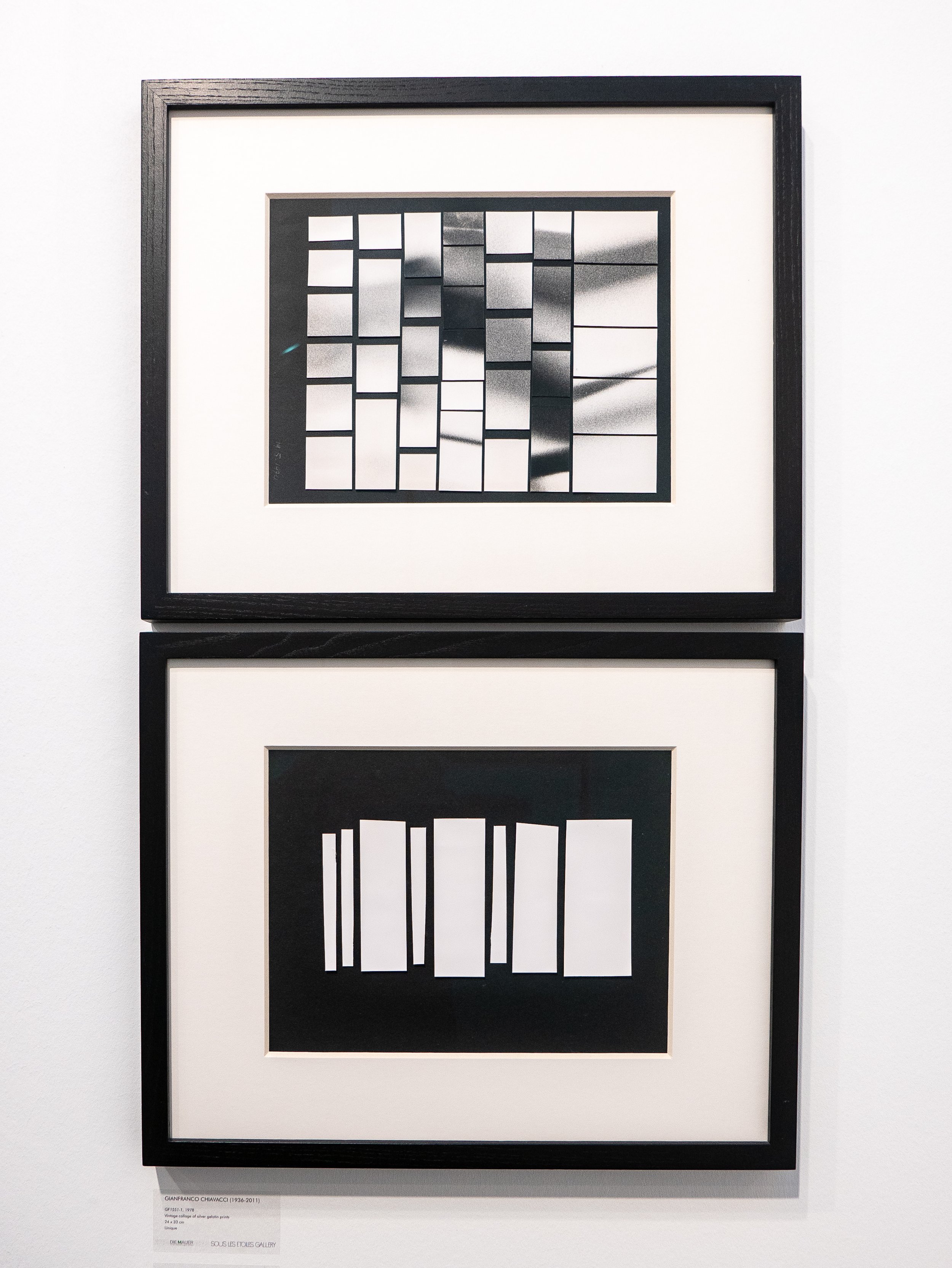

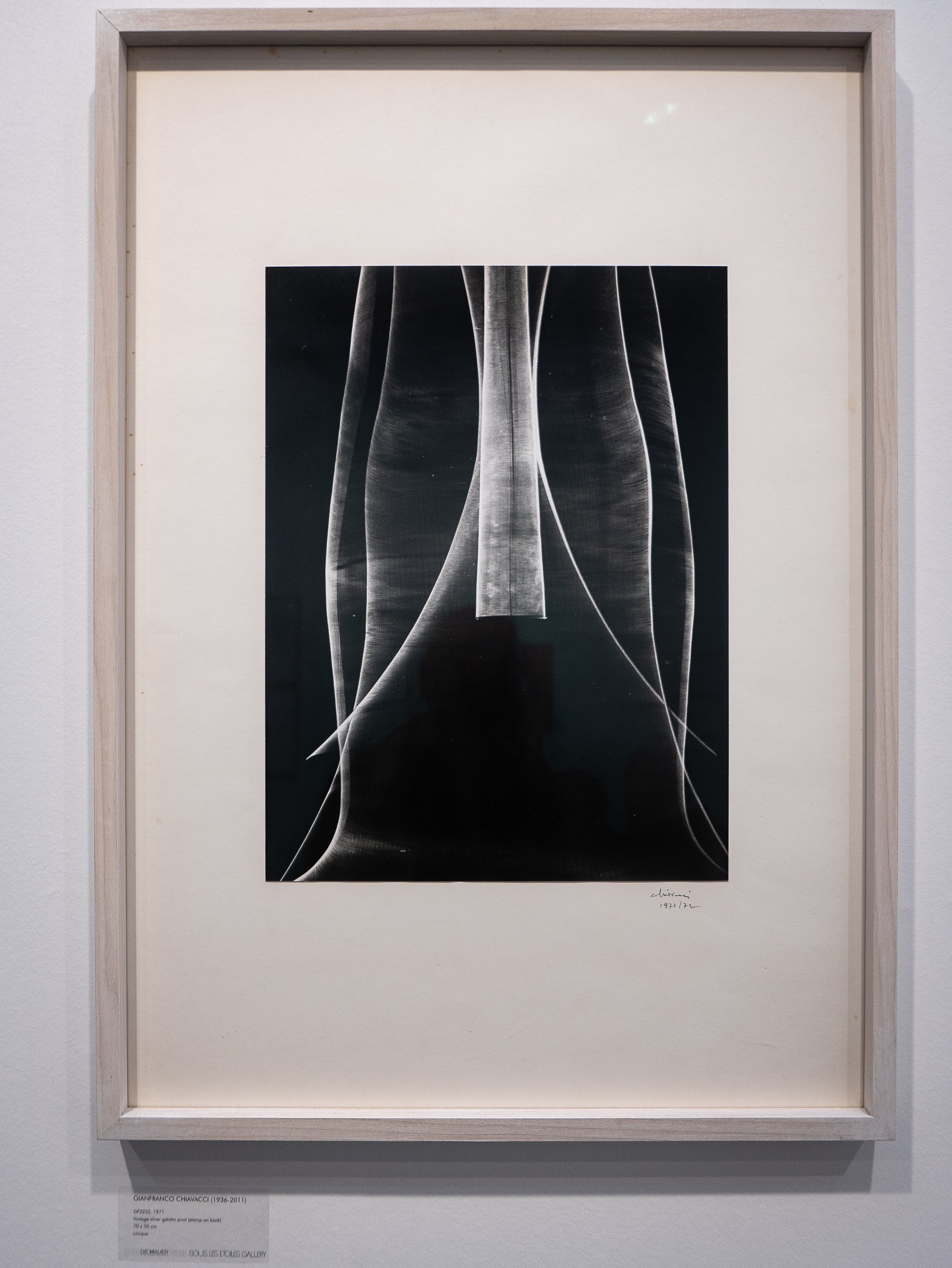

Spending a day at Paris Photo can be quite exhausting, due to the vast volume and wide range of photography on show but is one of the most stimulating ways of seeing at close hand, examples of a large selection of contemporary photography as well as original vintage prints by many of the finest photographers of the twentieth (and nineteenth) century. In practice, like Photo London, Paris Photo is essentially a four day long international dealers fair, showcasing largely fine art photography, with in addition a series of talks or interviews with several exhibiting photographers, a book fair and program of films, all under one (very large) roof.The large number of photographers represented makes it difficult to cover them comprehensively and unfair to single any one individual out. Selection of photos shown below represent a tiny fraction of what was available, concentrating on the more abstract or non-representational images, which I find myself increasingly drawn towards. They do not photograph well in the mixed lighting with lots of reflections and these are more of an aide memoire for myself and a record of the sorts of gallery layout that seemed effective, even in these relatively confined spaces. The selection includes a few original vintage prints by some of my personal favourites and several images by photographers that I have not previously encountered.

It was probably a mistake to try to see all of this in one day and the network of gallery stalls with a seething crowd of people actually makes it quite difficult to know if you have seen everything anyway. I spent seven hours going round the exhibits and tried to attend two of the Artist's Talks (one was in French a long way above my school days level), without stopping for a break as the queues for refreshment or food were enormous and I think I pretty much got there.

It was probably a mistake to try to see all of this in one day and the network of gallery stalls with a seething crowd of people actually makes it quite difficult to know if you have seen everything anyway. I spent seven hours going round the exhibits and tried to attend two of the Artist's Talks (one was in French a long way above my school days level), without stopping for a break as the queues for refreshment or food were enormous and I think I pretty much got there. If I did go again I would plan to spend at least two days, plan ahead cherry-picking what I really wanted to see and make sure I get in early for a seat for any of the talks that I didn't want to miss. Although relatively poorly organised, the Paris Photo website is an excellent ongoing resource with videos of many of the interviews from this and from previous years.https://www.parisphoto.com/en/Home/

If I did go again I would plan to spend at least two days, plan ahead cherry-picking what I really wanted to see and make sure I get in early for a seat for any of the talks that I didn't want to miss. Although relatively poorly organised, the Paris Photo website is an excellent ongoing resource with videos of many of the interviews from this and from previous years.https://www.parisphoto.com/en/Home/

Don McCullin at Tate Britain

The other 'blockbuster' exhibition of photography currently showing in London, is a very substantial retrospective at Tate Britain of the work of Don McCullin, the first photographer to have been given this accolade. Built in 1892 (as the National Gallery of British Art), in contrast to the brutalist concrete of the South Bank, this is a more refined traditional Victorian art gallery with a classical portico entrance and a central dome. The layout of the exhibition also followed relatively traditional lines; exhibition quality monochrome silver gelatin prints (all printed by McCullin in his own darkroom), window mounted in plain black frames, evenly spaced as single images or in small groups and centered at eye level around the walls of eight substantial rooms. The photographs were presented in roughly chronological order, grouped geographically starting with his earliest images of gang members in east London in the late 1950's and moving on to images of conflict zones and famines in Berlin, Cyprus, the Middle East, Vietnam and Cambodia, Sudan, Biafra as well as those showing the effects of de-industrialisation, social deprivation, poverty and homelessness in London and Northern England. The captions were mostly simple place names but two or three images in each room had more detailed explanations, describing McCullin's own insights about the situations he found himself in.I already knew his work well from several of his books and having written an essay about his photography in Year 1 of the FdA course. There were no particular surprises on offer but the volume, range and power of the photographs was as impressive as anticipated, to the point of becoming almost overwhelming. These subject matter of these images is dark, moving, poignant, even shocking but the manifest empathy of the photographer for the individuals affected, the victims of these tragedies and his desire to ensure that their stories are told, totally dispels any notion of sensationalisation or exploitation. This impression is confirmed by Colin Jacobsen in his article about the exhibition in the British Journal of Photography, who also quotes Harold Evans, McCullin's former editor at The Sunday Times "He cared about the victims, the collateral damage" and "He couldn't express it in words, but he expressed it in his photography".Although the gallery was busy, the experience of being able to examine close up, the quality in the detail of these prints, from negatives exposed in often unimaginably challenging circumstances, made the journey worthwhile. This was particularly true of a group of his later photographs presented in the final room of the exhibition, some landscape images made near his home on the Somerset Levels.

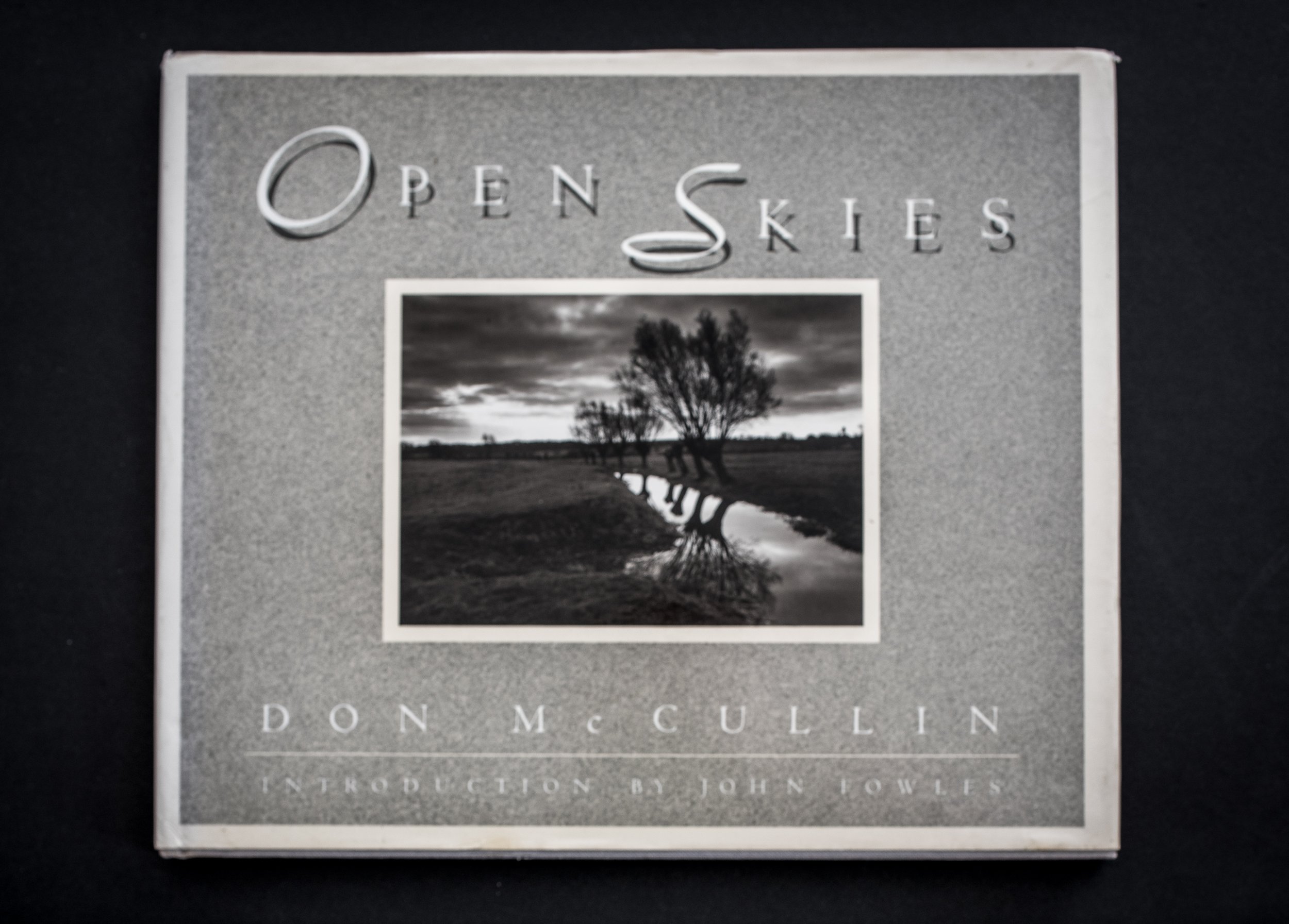

The other 'blockbuster' exhibition of photography currently showing in London, is a very substantial retrospective at Tate Britain of the work of Don McCullin, the first photographer to have been given this accolade. Built in 1892 (as the National Gallery of British Art), in contrast to the brutalist concrete of the South Bank, this is a more refined traditional Victorian art gallery with a classical portico entrance and a central dome. The layout of the exhibition also followed relatively traditional lines; exhibition quality monochrome silver gelatin prints (all printed by McCullin in his own darkroom), window mounted in plain black frames, evenly spaced as single images or in small groups and centered at eye level around the walls of eight substantial rooms. The photographs were presented in roughly chronological order, grouped geographically starting with his earliest images of gang members in east London in the late 1950's and moving on to images of conflict zones and famines in Berlin, Cyprus, the Middle East, Vietnam and Cambodia, Sudan, Biafra as well as those showing the effects of de-industrialisation, social deprivation, poverty and homelessness in London and Northern England. The captions were mostly simple place names but two or three images in each room had more detailed explanations, describing McCullin's own insights about the situations he found himself in.I already knew his work well from several of his books and having written an essay about his photography in Year 1 of the FdA course. There were no particular surprises on offer but the volume, range and power of the photographs was as impressive as anticipated, to the point of becoming almost overwhelming. These subject matter of these images is dark, moving, poignant, even shocking but the manifest empathy of the photographer for the individuals affected, the victims of these tragedies and his desire to ensure that their stories are told, totally dispels any notion of sensationalisation or exploitation. This impression is confirmed by Colin Jacobsen in his article about the exhibition in the British Journal of Photography, who also quotes Harold Evans, McCullin's former editor at The Sunday Times "He cared about the victims, the collateral damage" and "He couldn't express it in words, but he expressed it in his photography".Although the gallery was busy, the experience of being able to examine close up, the quality in the detail of these prints, from negatives exposed in often unimaginably challenging circumstances, made the journey worthwhile. This was particularly true of a group of his later photographs presented in the final room of the exhibition, some landscape images made near his home on the Somerset Levels. I have a second hand copy from America of his book 'Open Skies' published in 1989, which includes these photographs and have previously felt that they were so dark that they had been over-printed, blocking up the details in the shadow areas. Having now seen these photographs 'in the flesh', the detail in the shadows has been retained, the quality is superb and I can appreciate that the problem in the book is down to the reproduction of the images, emphasising the value in being able to get to see the original prints. In his introduction to the book, John Fowles speculates that the darkness of these images is a reflection of McCullin's 'state of mind' following his years of covering human tragedies all around the world, along with the tragedies of his own personal life.Thirty years further down the line and now aged 83, McCullin commented on this in a recent television documentary for BBC Four, confirming that as he has got older, he feels the need to make his prints darker, yet his mood now seems lighter and what was most apparent was his humility and that he still cares passionately about people, regardless of their background but especially the less fortunate among us.https://www.tate.org.uk/what's-on/tate-britain/exhibition/don-mccullinJacobsen, C., "Endframe, Don McCullin': British Journal of Photography, Issue 7882, p 98, April 2019.McCullin, D., 'Open Skies': Harmony Books, New York, 1989. (Originally published in Great Britain by Jonathon Cope).https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m0002dv0/don-mccullin-looking-for-england, Accessed on 10/4/2019

I have a second hand copy from America of his book 'Open Skies' published in 1989, which includes these photographs and have previously felt that they were so dark that they had been over-printed, blocking up the details in the shadow areas. Having now seen these photographs 'in the flesh', the detail in the shadows has been retained, the quality is superb and I can appreciate that the problem in the book is down to the reproduction of the images, emphasising the value in being able to get to see the original prints. In his introduction to the book, John Fowles speculates that the darkness of these images is a reflection of McCullin's 'state of mind' following his years of covering human tragedies all around the world, along with the tragedies of his own personal life.Thirty years further down the line and now aged 83, McCullin commented on this in a recent television documentary for BBC Four, confirming that as he has got older, he feels the need to make his prints darker, yet his mood now seems lighter and what was most apparent was his humility and that he still cares passionately about people, regardless of their background but especially the less fortunate among us.https://www.tate.org.uk/what's-on/tate-britain/exhibition/don-mccullinJacobsen, C., "Endframe, Don McCullin': British Journal of Photography, Issue 7882, p 98, April 2019.McCullin, D., 'Open Skies': Harmony Books, New York, 1989. (Originally published in Great Britain by Jonathon Cope).https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m0002dv0/don-mccullin-looking-for-england, Accessed on 10/4/2019

Return to Manchester : Martin Parr

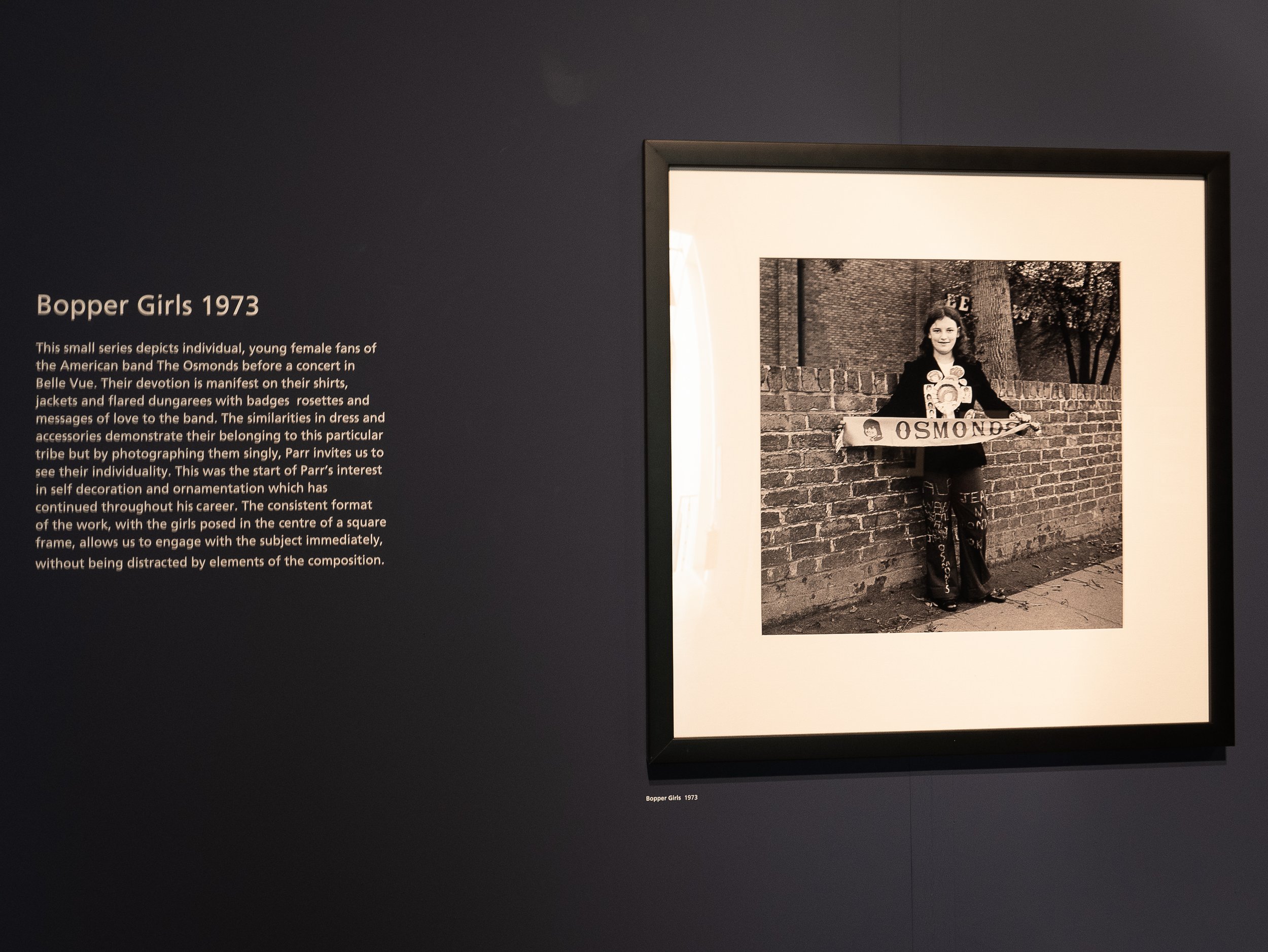

This exhibition currently showing at Manchester Art Gallery focuses on Martin Parr's long term engagement with the people of the city and the surrounding industrial towns of the North West, which form the region of Greater Manchester. From his first student projects in 1970, over a period of nearly fifty years, he has returned regularly and his work now constitutes a substantial documentary record of the changes in the fabric of city's buildings along with its' cultural and social development from an industrial region to modern twenty-first century metropolis.By concentrating on the lives of the inhabitants he has recorded the effects of on one hand, the social deprivation resulting from de-industrialization and on the other, the gentrification of parts of the city, which closely mirrors the changes seen in other major UK cities. The thread which runs through these projects is his ability to capture the warmth and resilience of the people he photographed along the way, especially those from the working class areas. His early black and white photographs are still resonant of the times they covered. His series from the psychiatric hospital in Prestwich are especially poignant and his medium format photographs of girl 'teenyboppers’ manage to capture a sense of the personalities of the teenagers as well as the period detail of their clothing. The layout of the exhibition seamlessly follows his switch to working in colour in the early 1980’s, making the change appear to fit logically with the ways in which that period is now usually remembered (colour in television screens, magazines and newspaper supplements, at that time becoming the norm). The colours recorded in the details of people's everyday lives; shop windows, home decor, clothing, are particularly resonant of the times.

His early black and white photographs are still resonant of the times they covered. His series from the psychiatric hospital in Prestwich are especially poignant and his medium format photographs of girl 'teenyboppers’ manage to capture a sense of the personalities of the teenagers as well as the period detail of their clothing. The layout of the exhibition seamlessly follows his switch to working in colour in the early 1980’s, making the change appear to fit logically with the ways in which that period is now usually remembered (colour in television screens, magazines and newspaper supplements, at that time becoming the norm). The colours recorded in the details of people's everyday lives; shop windows, home decor, clothing, are particularly resonant of the times. More than a few contemporary photographers (including myself) have commented that they find his more recent digital colour images less easy to relate to, which seems difficult to comprehend given that his working methods and subject matter have not significantly changed and the colours and clarity of detail in the images are if anything truer to life. Perhaps now we already know his work so well that there are now simply fewer surprises or the use of digital capture somehow lacks the resonance we felt looking at the earlier work with analogue materials. Alternatively could it be that these images are too close to what we see around us and in the media every day - does familiarity breed contempt? Perhaps if we are still here, we might respond to them more positively in another twenty years time.http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/martin-parr/

More than a few contemporary photographers (including myself) have commented that they find his more recent digital colour images less easy to relate to, which seems difficult to comprehend given that his working methods and subject matter have not significantly changed and the colours and clarity of detail in the images are if anything truer to life. Perhaps now we already know his work so well that there are now simply fewer surprises or the use of digital capture somehow lacks the resonance we felt looking at the earlier work with analogue materials. Alternatively could it be that these images are too close to what we see around us and in the media every day - does familiarity breed contempt? Perhaps if we are still here, we might respond to them more positively in another twenty years time.http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/martin-parr/

Diane Arbus : 'in the beginning'

The Hayward gallery in the South Bank Centre in London is currently showing an exhibition of original monochrome analogue photographs made by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) between 1956 and 1962. Although from the age of eighteen, she had worked in fashion and advertising alongside her husband, the actor and photographer Allan Arbus, she did not embark on the work for which she is now well known, until she was in her early thirties. At that time, while she was studying with Lisette Model, she began to make photographs of people she met in the street in and around the less affluent areas of New York City and Coney Island. These images, best described as her early formative work, were made using 35mm film cameras printed at 6 x 9 inches by Arbus herself and two thirds of them have not been shown previously in the U.K.

The Hayward gallery in the South Bank Centre in London is currently showing an exhibition of original monochrome analogue photographs made by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) between 1956 and 1962. Although from the age of eighteen, she had worked in fashion and advertising alongside her husband, the actor and photographer Allan Arbus, she did not embark on the work for which she is now well known, until she was in her early thirties. At that time, while she was studying with Lisette Model, she began to make photographs of people she met in the street in and around the less affluent areas of New York City and Coney Island. These images, best described as her early formative work, were made using 35mm film cameras printed at 6 x 9 inches by Arbus herself and two thirds of them have not been shown previously in the U.K. As perhaps expected, the quality of the images does not equate with that of her much better known later medium format photographs but the gallery did not permit photography in this exhibition so I have no available examples to show. There was a small area, separate from the main body of the exhibition, showing a folio of ten of her medium format prints (printed at 20 x 20 inches) and the difference in quality was clearly evident. That said, the earlier photographs explored a wider range of subject matter, informal portraits, street photography, people in fairgrounds or at the beach, cinema and theatre audiences and people through restaurant windows. A few images appeared to be screen shots on television sets and there were some found still lives on wet pavements. Several of the prints showed pronounced grain effects and in some (especially the low-light images) the focus was quite soft but this imparted a degree of freshness or rawness to the work which appeared less planned or staged than her photographs from the mid 1960's onwards. This would be an important collection for anyone studying Diane Arbus, demonstrating the early stages of the evolution of her working practice.

As perhaps expected, the quality of the images does not equate with that of her much better known later medium format photographs but the gallery did not permit photography in this exhibition so I have no available examples to show. There was a small area, separate from the main body of the exhibition, showing a folio of ten of her medium format prints (printed at 20 x 20 inches) and the difference in quality was clearly evident. That said, the earlier photographs explored a wider range of subject matter, informal portraits, street photography, people in fairgrounds or at the beach, cinema and theatre audiences and people through restaurant windows. A few images appeared to be screen shots on television sets and there were some found still lives on wet pavements. Several of the prints showed pronounced grain effects and in some (especially the low-light images) the focus was quite soft but this imparted a degree of freshness or rawness to the work which appeared less planned or staged than her photographs from the mid 1960's onwards. This would be an important collection for anyone studying Diane Arbus, demonstrating the early stages of the evolution of her working practice. For my own research, perhaps the most striking aspect of this exhibition was the way in which the work was presented (I made the one photograph shown above before I noticed the small 'No Photography' sign on the plain wall on the right of the image). There were no photographs on the perimeter walls of the space, which were painted in a deep rich matt navy blue (almost black) colour. As shown, the main gallery contained about forty evenly spaced free standing pillars painted in matt white with one photograph only on each long side. The prints were traditionally window mounted in dark metallic pewter like frames and the immediate impressions created by the design were of light airiness and opulently high quality minimalist precision, with a hushed atmosphere indicating genuine reverence for the work being presented.Diane Arbus tragically took her own life in 1971 and I think she would have been pleased with this exhibition but although the gallery has gone to great lengths (and expense) to create an impressive setting for the photographs, I felt to an extent that the design almost overwhelmed the actual images, perhaps reinforcing my impression that this was not her best work. In the information at the gallery entrance, the curators explained that the work had not been arranged in any chronological order and that viewers should feel free to find their own route around the gallery at their own pace. This worked well while the gallery was initially quiet but it filled up quite quickly and I was conscious of people around me moving from pillar to pillar in different directions at different speeds to the extent that I felt under pressure to move on, to avoid holding them up. Although many were individually fascinating, the disparate selection of images were placed surprisingly randomly with no obvious attempt to formally sequence them. This could of course have been an attempt to subliminally re-create the feel of the circumstances in which they were created but overall it felt more like a triumph of style over substance.https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/diane-arbus-beginninghttps://www.biography.com/people/diane-arbus-9187461

For my own research, perhaps the most striking aspect of this exhibition was the way in which the work was presented (I made the one photograph shown above before I noticed the small 'No Photography' sign on the plain wall on the right of the image). There were no photographs on the perimeter walls of the space, which were painted in a deep rich matt navy blue (almost black) colour. As shown, the main gallery contained about forty evenly spaced free standing pillars painted in matt white with one photograph only on each long side. The prints were traditionally window mounted in dark metallic pewter like frames and the immediate impressions created by the design were of light airiness and opulently high quality minimalist precision, with a hushed atmosphere indicating genuine reverence for the work being presented.Diane Arbus tragically took her own life in 1971 and I think she would have been pleased with this exhibition but although the gallery has gone to great lengths (and expense) to create an impressive setting for the photographs, I felt to an extent that the design almost overwhelmed the actual images, perhaps reinforcing my impression that this was not her best work. In the information at the gallery entrance, the curators explained that the work had not been arranged in any chronological order and that viewers should feel free to find their own route around the gallery at their own pace. This worked well while the gallery was initially quiet but it filled up quite quickly and I was conscious of people around me moving from pillar to pillar in different directions at different speeds to the extent that I felt under pressure to move on, to avoid holding them up. Although many were individually fascinating, the disparate selection of images were placed surprisingly randomly with no obvious attempt to formally sequence them. This could of course have been an attempt to subliminally re-create the feel of the circumstances in which they were created but overall it felt more like a triumph of style over substance.https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/hayward-gallery-art/diane-arbus-beginninghttps://www.biography.com/people/diane-arbus-9187461

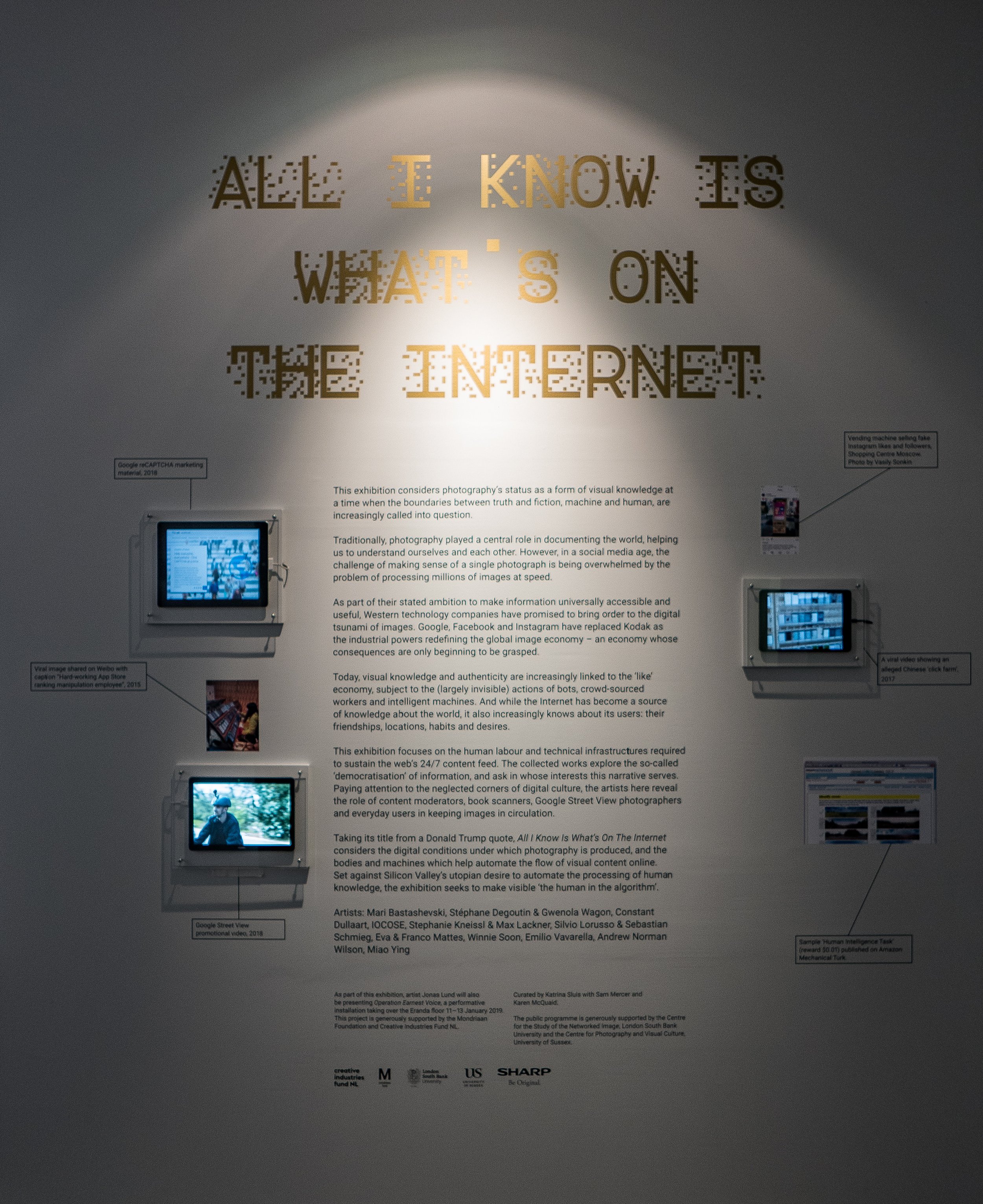

All I know is what's on the internet

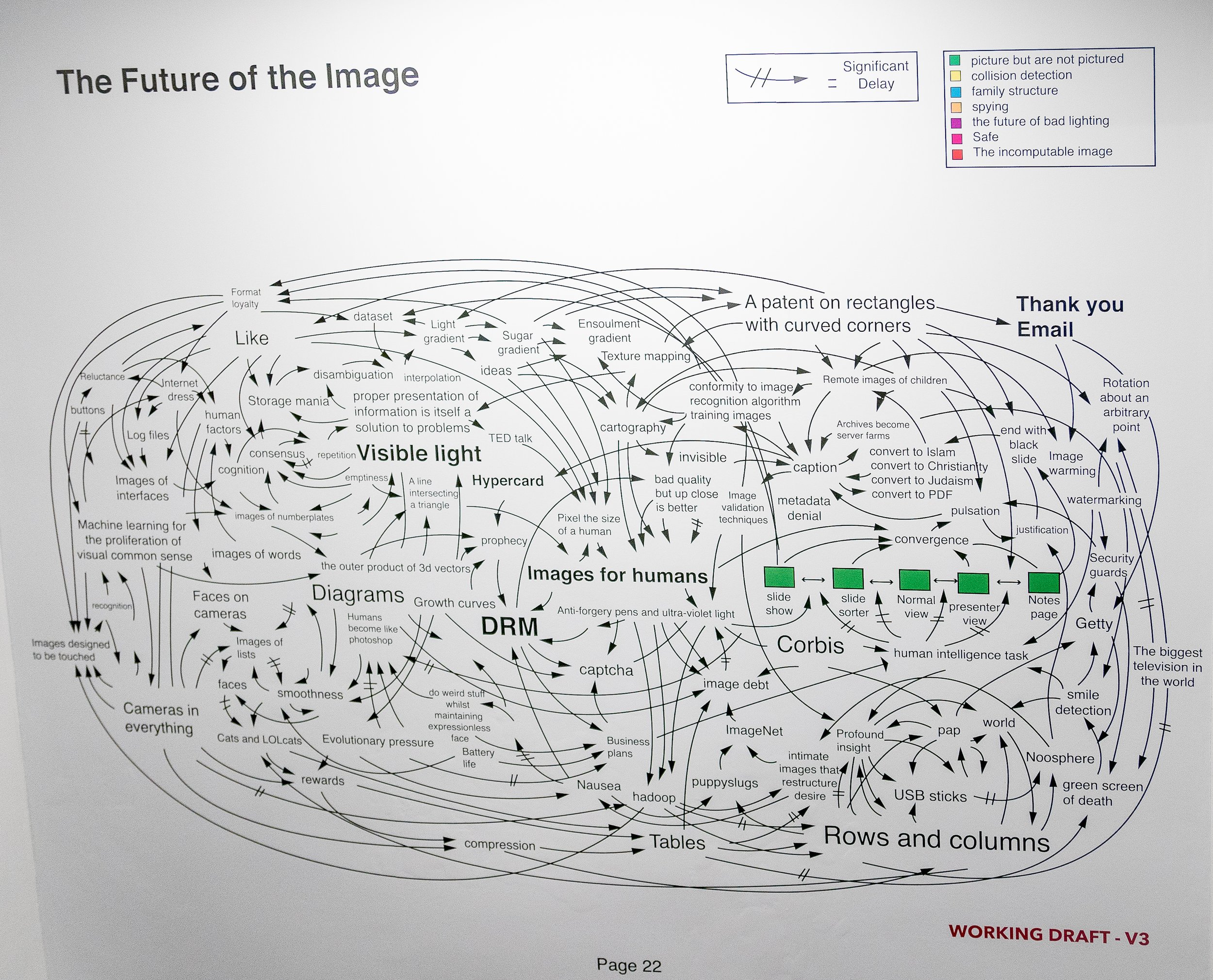

This exhibition currently showing at the Photographers' Gallery in London is a study of a group of artists examining several aspects of the effects of digital imaging and online media on the ways in which photography is used in contemporary cultures. The title is a quote from one of Donald Trump's press interviews during the 2016 US presidential election campaign which perhaps reflects the less than positive effects some of the contributors have uncovered in their research. Although the impression is often given that everything that happens on the internet is fully automated, the exhibition looks at the huge workforce required to support the infrastructure of the involved technology companies, service providers, search engines and social media platforms, including among others programmers, online support teams, 'clickworkers', content moderators, people employed to copy books for online publication and google street view camera operators. The issues of manipulation of cultural tastes (the 'like' economy and false social media accounts) and of unequal access to online content in different parts of the world are also explored. This was not a typical photography exhibition in the sense of the images being visually or aesthetically stimulating but it was certainly thought provoking and there was a lot to take in. The image which left the strongest impression was a mind map produced for the Photographer's Gallery by Mathew Fuller and Olgia Goriunova, exploring the future role of photography which was described as a deliberately 'incomprehensible diagram' based on a Powerpoint slide from a presentation by General Stanley A. McChrystal who was quoted as saying "when we understand that slide we will have won the war"

This was not a typical photography exhibition in the sense of the images being visually or aesthetically stimulating but it was certainly thought provoking and there was a lot to take in. The image which left the strongest impression was a mind map produced for the Photographer's Gallery by Mathew Fuller and Olgia Goriunova, exploring the future role of photography which was described as a deliberately 'incomprehensible diagram' based on a Powerpoint slide from a presentation by General Stanley A. McChrystal who was quoted as saying "when we understand that slide we will have won the war" There can be no doubt that the role of still photography is changing rapidly but where it will end up in the future is anybody's guess. I left this exhibition feeling I need to engage more actively with the online world if I am ever going to make any sense of it. Perhaps the exercise of writing this blog will prove to be a good starting point.https://thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internethttps://thehill.com/blogs/ballot-box/presidential-races/272824-trump-all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internetPhotographs of the installation used were taken at the exhibition by the blog author.Update 17 Feb 2019 Have recently seen the film 'WhiskyTangoFoxtrot' which was based on the memoir of the American journalist Kim Barker. A copy of the original US Army diagram on which the above image is based appears in a scene set in an army intelligence briefing room.https://www.comingsoon.net/movie/whiskey-tango-foxtrot-2016#/slide/1

There can be no doubt that the role of still photography is changing rapidly but where it will end up in the future is anybody's guess. I left this exhibition feeling I need to engage more actively with the online world if I am ever going to make any sense of it. Perhaps the exercise of writing this blog will prove to be a good starting point.https://thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internethttps://thehill.com/blogs/ballot-box/presidential-races/272824-trump-all-i-know-is-whats-on-the-internetPhotographs of the installation used were taken at the exhibition by the blog author.Update 17 Feb 2019 Have recently seen the film 'WhiskyTangoFoxtrot' which was based on the memoir of the American journalist Kim Barker. A copy of the original US Army diagram on which the above image is based appears in a scene set in an army intelligence briefing room.https://www.comingsoon.net/movie/whiskey-tango-foxtrot-2016#/slide/1

The Photographers' Gallery, London

While in London last month I also visited the Photographers' Gallery where the two current exhibitions on show are 'Roman Vishniac Rediscovered' (in collaboration with the Jewish Museum of London) and 'All I Know is What's on the Internet' (a quote from Donald Trump). I will consider the second of these in a separate blog.

While in London last month I also visited the Photographers' Gallery where the two current exhibitions on show are 'Roman Vishniac Rediscovered' (in collaboration with the Jewish Museum of London) and 'All I Know is What's on the Internet' (a quote from Donald Trump). I will consider the second of these in a separate blog. The larger exhibition, on Levels 4 and 5 of the gallery is an extensive retrospective of the Russian born American photographer Roman Vishniac (1897-1990). Vishniac had moved from Moscow to Berlin to escape the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1920 and his best known body of work is a large social documentary portrait of the Jewish population of Eastern Europe, mainly Berlin and Warsaw in the inter-war years, coinciding with the evolution of modernism and the rise of fascism with the resultant persecution of these communities. It is a unique document of the dramatic changes in these societies from a atmosphere open to artistic expression and social multiculturalism to the sectarianism and oppression of the Nazi regime and the populations decimated by their policies.The layout of most of the exhibition is a traditional wall mounted chronological sequence of very fine vintage (and some newly re-printed) monochrome prints, including studio and candid portraits as well as street photography and images of agricultural workers. On escaping from Germany in the mid-1930's, he moved to the USA and quickly established a successful commercial portrait studio. His other interest was the photography of microscopic life forms and his pioneering work in colour photomicrography led to an academic career and professorships in biology and fine art photography in several American universities - a selection of these images were presented in a separate room from the main exhibition as a projected slide show along with several of his publications displayed in glass cases.The quality of his work is very impressive and the social documentary work is genuinely moving but aside from this and his imaginative use of atmospheric shadows, the relevance to my own current practice is of limited relevance.www.thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/roman-vishniac-rediscovered

The larger exhibition, on Levels 4 and 5 of the gallery is an extensive retrospective of the Russian born American photographer Roman Vishniac (1897-1990). Vishniac had moved from Moscow to Berlin to escape the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1920 and his best known body of work is a large social documentary portrait of the Jewish population of Eastern Europe, mainly Berlin and Warsaw in the inter-war years, coinciding with the evolution of modernism and the rise of fascism with the resultant persecution of these communities. It is a unique document of the dramatic changes in these societies from a atmosphere open to artistic expression and social multiculturalism to the sectarianism and oppression of the Nazi regime and the populations decimated by their policies.The layout of most of the exhibition is a traditional wall mounted chronological sequence of very fine vintage (and some newly re-printed) monochrome prints, including studio and candid portraits as well as street photography and images of agricultural workers. On escaping from Germany in the mid-1930's, he moved to the USA and quickly established a successful commercial portrait studio. His other interest was the photography of microscopic life forms and his pioneering work in colour photomicrography led to an academic career and professorships in biology and fine art photography in several American universities - a selection of these images were presented in a separate room from the main exhibition as a projected slide show along with several of his publications displayed in glass cases.The quality of his work is very impressive and the social documentary work is genuinely moving but aside from this and his imaginative use of atmospheric shadows, the relevance to my own current practice is of limited relevance.www.thephotographersgallery.org/whats-on/exhibition/roman-vishniac-rediscovered

Viviane Sassen

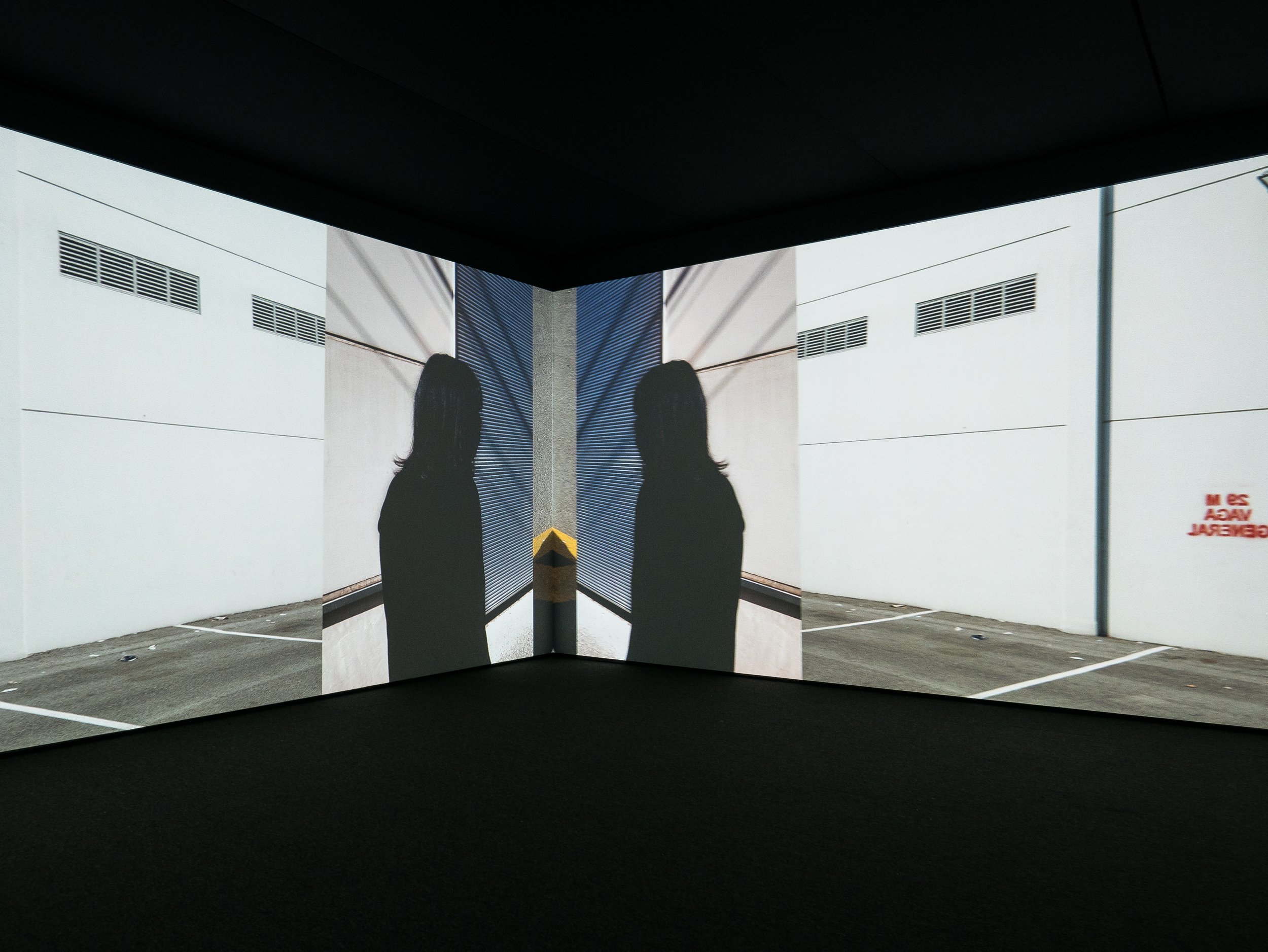

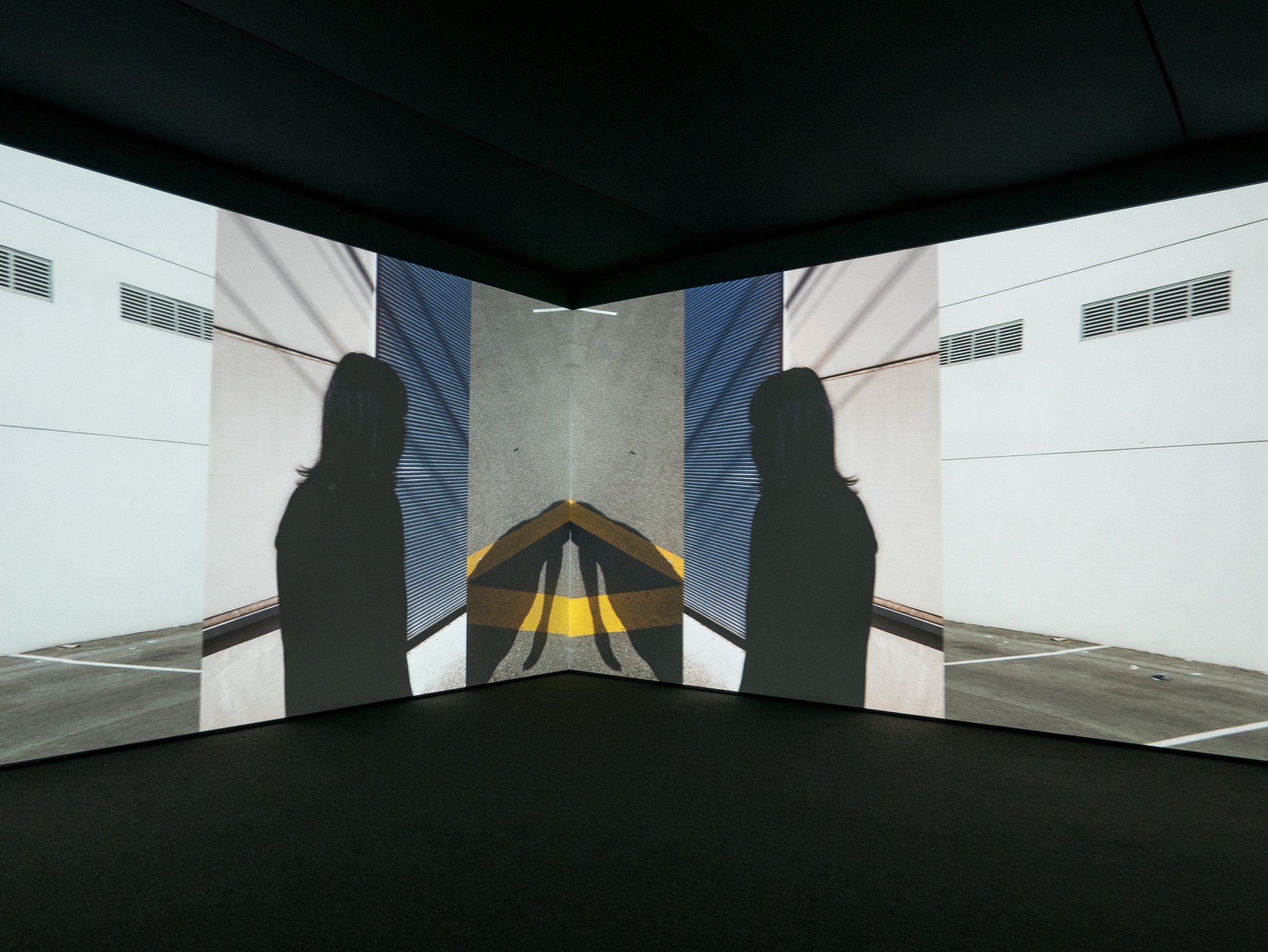

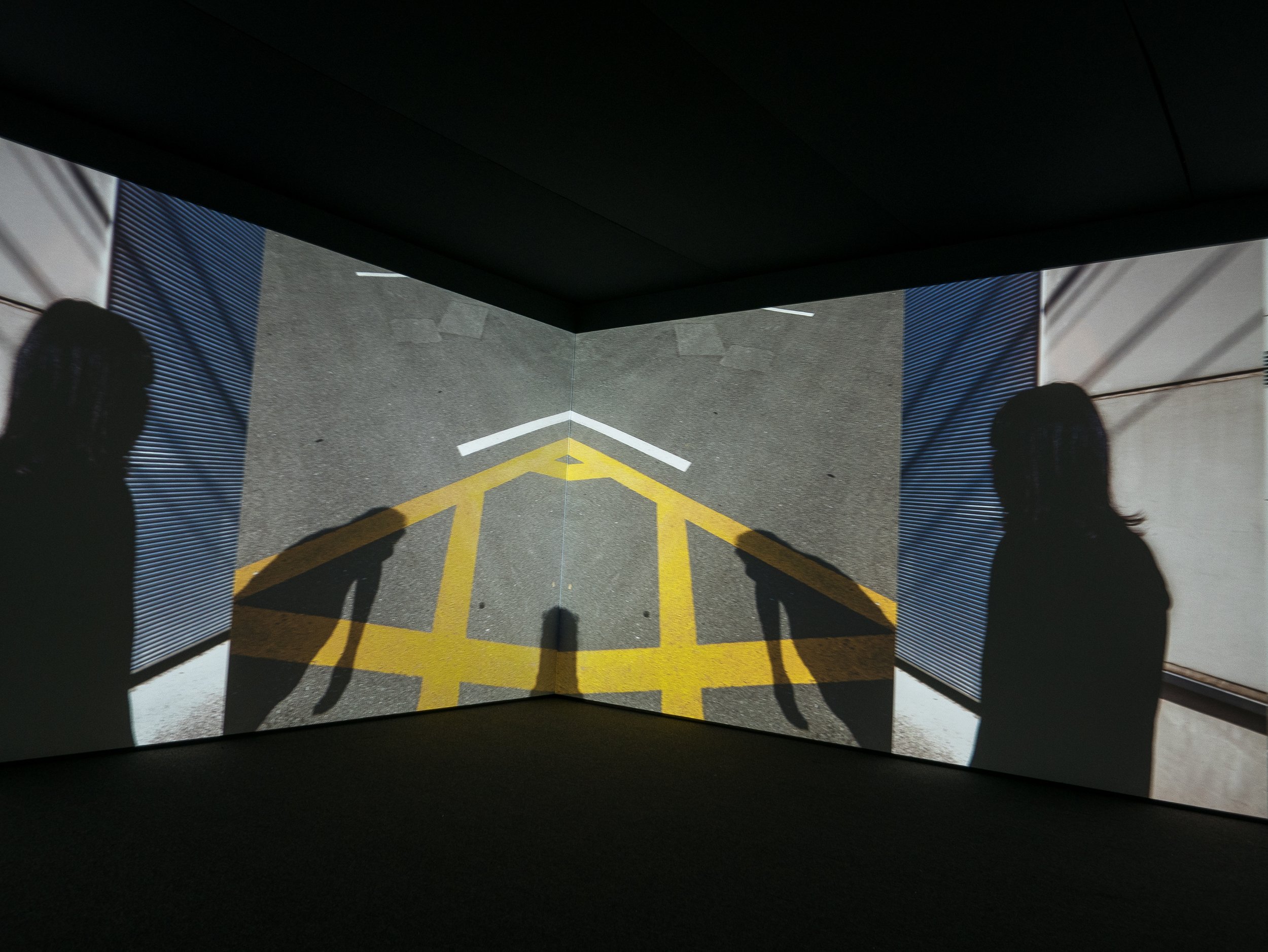

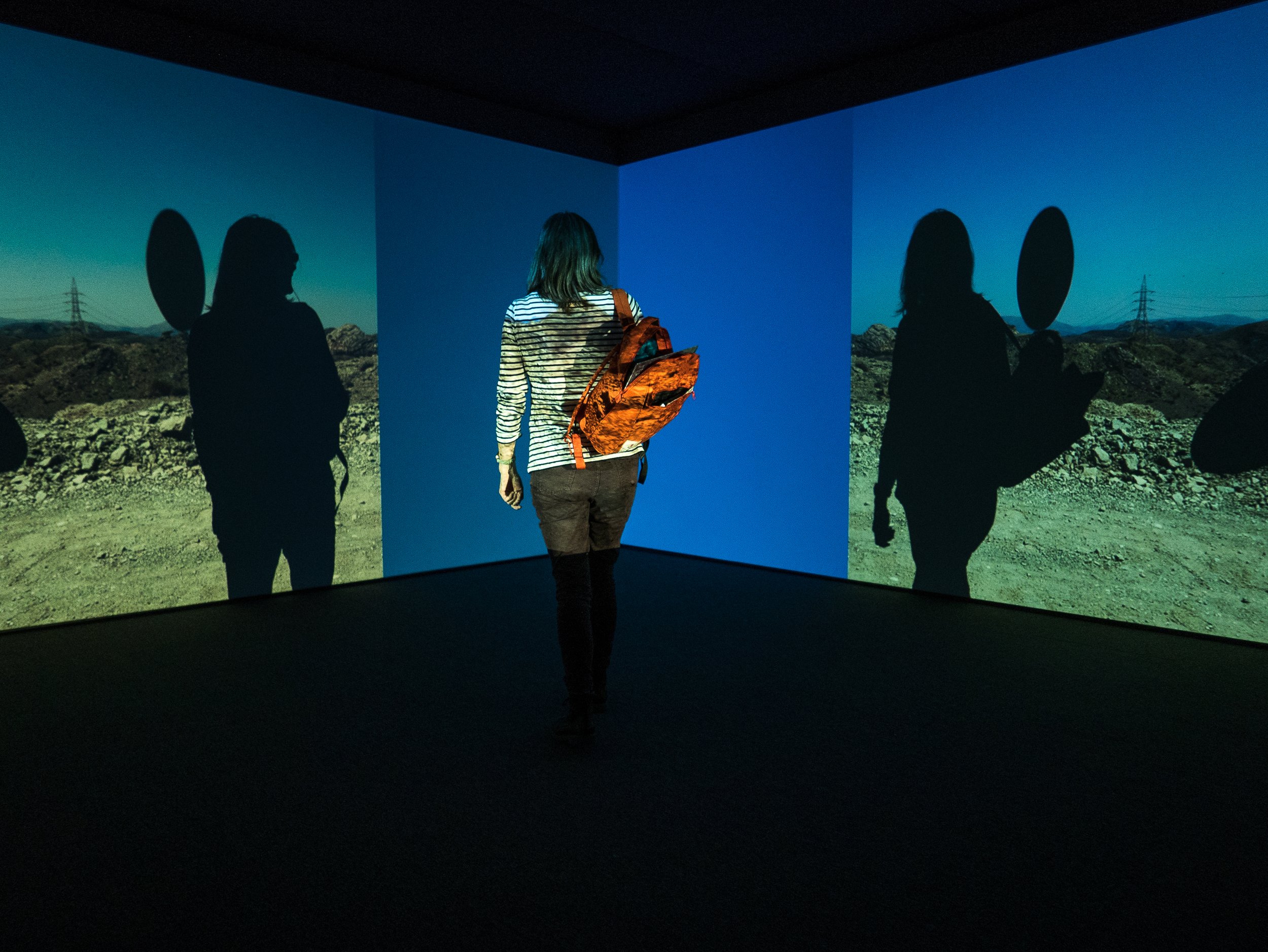

Hepworth Gallery Wakefield, October 2018Also showing contemporaneously with the “Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain” exhibition at the Hepworth was an exhibition of the work of the Dutch fine art photographer Viviane Sassen and for several reasons, the placement of her work in the adjacent gallery was an inspired curatorial decision. Born in Amsterdam in 1972, Vivienne Sassen initially chose to study fashion and design in Arnhem in 1990 which led to a brief period working as a fashion model while also moving to the other side of the camera to study photography in Utrecht from 1992 until 1996, then back to Arnhem where she completed a Masters degree in fine art in 1998. She has a very successful career as a fashion photographer and although she still lives and works in Amsterdam, she spent several years in her early childhood in East Africa, which subsequently proved to be a major influence on her life and her work, much of which has been made on return visits to Africa as an adult. In an interview for the exhibition catalogue she has explained that although she is now exhibiting mainly her fine art photography, she still derives much of her energy from fashion which has become an outlet for her exuberance. “In fashion I can express my extroverted side; in my more personal work, the introverted side” (Ammerlaan, 2018). In addition to the parallels with the career of Lee Miller, these more personal images often explore the ideas which are commonly associated with Surrealism – dreams, childhood memories, chance associations, eroticism and death. Her work also exploits some of the techniques favoured by the surrealist artists including the use of collage, mixed media, unexpected juxtapositions, disjointed bodies, incongruous colour combinations, mirrors with reflected or refracted light, shadows and on occasions even solarisation. While her books and previous exhibitions of her work have each been based on specific individual projects, on this occasion, working in close collaboration with the curators, the wall mounted photographs have been presented as small groups of images, each consisting of photographs chosen from several different bodies of her work over the last ten years. Through unexpected juxtapositions these individual ‘image poems’ are held together by the themes and motifs which have been features running through her work over this time.The most striking first impression of the images is her use of colour, bright lighting and graphic shapes, drawing on her experience in fashion photography as evident in the quality of her photographic technique, compositional design skills, her ability to work effectively with models and in the presentation of the images . The Hepworth is a gallery designed with large bright open spaces to accommodate the large three-dimensional sculptural works with which it is more often associated. This however also makes it an ideal setting for showcasing her work by giving the groups of wall mounted photographs plenty of ‘room to breathe’. In addition, the middle of the gallery space was occupied by a large white cube which formed the centrepiece (literally) of the exhibition. The exterior of this cube made it appear simply as additional wall space for several further groups of photographs but the interior, accessed by a light-trap door in one corner, was a large square projection room, the innovative design of which is difficult to describe clearly in words alone (hence the attached images).The two walls opposite the entrance to the space were filled by large white projection screens and the images projected onto them consisted of a rolling montage of continually moving high contrast colourful still photographs with graphic shapes, shadows and silhouettes of people, animals or trees and foliage, against backgrounds of desert landscapes, blue skies, urban facades or tarmac roads with lane bright markings. The images projected on the left hand wall flowed across the screen from right to left, while those on the right hand screen were mirror images of the same photographs simultaneously moving from left to right. The resulting appearance this created in that corner of the space was a continuously moving ‘Rorschach effect’ metamorphosis of abstract shapes, patterns and colours. The other two walls in the space were large mirrors, each with a small central aperture for the two projector beams, these mirrors reflecting in focus the continually moving projected images on the opposite walls. The effect for the viewer was further enhanced when on moving into the room they crossed the projector beams, resulting in their own shadows interacting with the shadows and silhouettes in the photographs, such that they effectively became part of the evolving images. (I did say it was difficult to explain in words). The degree of technical precision required to achieve the synchronisation of this installation is itself a major achievement and to combine this with the thought-provoking imagery it produced can only be described as an artistic triumph.My initial interest in visiting this exhibition, in relation to my own work, was stimulated by the little I already knew about her work with shadows on desert sand to create abstract compositions, using mirrors and coloured gels. The complex themes explored in her figurative imagery show that this is the work of a mature, engaged artist and the ground-breaking centrepiece projection installation produced a contemporary surreal experience, which lifted this exhibition to an entirely different level. Although I had previously only associated surrealism with the movement active in the period between the two world wars and into the 1950's, I am now more aware of its lasting influence and continuing relevance to the present time.

Ammerlaan R. ‘A Shy Exhibitionist: the Loss and Longing of Viviane Sassen, Photographer and Artist’, In: Hot Mirror Ed. Holtz C., Prestel Verlag, Munich London New York, 2018.https://www.vivianesassen.com/news/https://www.wefolk.com/artists/vivianne-sassen/information

Ammerlaan R. ‘A Shy Exhibitionist: the Loss and Longing of Viviane Sassen, Photographer and Artist’, In: Hot Mirror Ed. Holtz C., Prestel Verlag, Munich London New York, 2018.https://www.vivianesassen.com/news/https://www.wefolk.com/artists/vivianne-sassen/information

Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain

Hepworth Gallery Wakefield, October 2018In photography circles the American born photographer Lee Miller (1907-1977) is best known for her work in fashion and war photography and perhaps for Man Ray’s photographs of her while she was his studio assistant/model/muse in Paris from 1929 to 1932. This wide-ranging exhibition explores her less well known role in the evolution and promotion of Surrealist art in Britain, from the 1930’s through to the early 1960’s, using her photographs of many of the active participants in the movement, their work and their exhibitions as well as the photographic work she exhibited alongside them. The works exhibited are a diverse collection of photographs by Lee Miller and artworks by the surrealist artists she knew and collaborated with, in the form of paintings, sculptures, some photographs, mixed media collages, posters, magazines, pamphlets, exhibition catalogues and promotional materials.Lee Miller’s work on show included some formal portraits from her studio in Paris with examples of the solarisation technique she developed along with Man Ray, informal portraits of surrealist artists in various settings, often when they visited the home she set up in England with Roland Penrose, some landscape work from the Mediterranean and Egypt, installation shots of surrealist exhibitions in London, some of her fashion work with Vogue during World War II, some of her wartime photographs on assignment in France, Germany and the holocaust concentration camps as well as the famous photograph of her in the bathtub in Hitler’s apartment in Berlin (by David E Scherman). The surrealist artworks exhibited had all been part of previous exhibitions in England in the years leading up to, during and after the war and included work by Miller herself and (among others) Roland Penrose (her second husband), Man Ray, Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington, Joan Miró, Paul Nash, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dali, Giorgio de Chirico, Eileen Agar, E.L.T. Mesens, Henry Moore, René Magritte and several other less well known English artists.The exhibition was organised in a series of rooms, with each of these covering separate periods in her career. They were arranged chronologically starting with her time in Paris, moving onto her moving to England, then covering the wartime years and finally, some of her work as a curator in the 1950’s and 1960’s. The overall feel of the exhibition was something akin to that of a history lesson and in that respect, it worked very well. The Lee Miller photographs from Paris, the informal portraits of the artists and the wartime photographs were all powerful images. The examples of studio portraits printed using ‘solarisation’ to create reversal of some of the tones in the images were especially effective and I felt there could have been more of these on show (Man Ray had taken the credit for inventing this effect but Miller later claimed that she had discovered it by chance - when developing a print she transiently switched on the room light after a mouse ran over her foot in his darkroom). While there were several very striking images among the work of the other artists on show, quite a few of them were surprisingly disappointing. The lighting in these galleries was kept quite low, presumably for conservation reasons and many of the paintings, drawings and posters seem to have faded and were quite drab in appearance. They would undoubtedly have been seen as strange, new, sensational, or even shocking when they were first shown but the ability of these surrealist images to astonish appears to have diminished with familiarity and with the passing of time*.Thinking back, a few weeks after visiting the exhibition, I can recall two images which I felt were particularly memorable. The first of these was a small exquisitely delicate painting by Yves Tanguy entitled ‘Imaginary Landscape’ (1933), a panoramic letterbox sized still life presented as a desert scene with several small unusual looking domestic objects and their shadows, similar in appearance to some of Salvador Dali’s more dramatic and fantastical desert landscapes but infinitely more subtle. The second was a pair of photographs by Lee Miller called ‘Untitled (Severed Breast from Radical Surgery in a Place Setting 1 and 2)’ (Paris, 1929). These are photographs of a surgical mastectomy specimen on a plate at a dinner table, with a knife and fork on either side. The first of these shows the skin ellipse and nipple/areola complex (showing evidence of retraction by the cancer) facing upwards and is clearly recognisable as a breast but the second has been placed with the skin facing downwards which in a black and white photograph makes the specimen look like a plate of minced meat. These images conform with the recurring surrealist themes of unexpected juxtaposition of finding unusual objects in everyday settings and depictions of fragmented or distorted body parts but could also indicate that Miller was commenting on the fact that the fragmented bodies often seen in surrealist images (usually by male artists) were almost always female. I am sure this image was felt to be shocking at the time it was made and suspect most people would still be shocked by it. As a retired surgeon who specialised in treating breast cancer patients my reaction is perhaps understandably less typical – rather than shock, I simply felt uneasy, considering how the patient would have felt if she had seen these photographs and the ethical issues of patient confidentiality and respect for her dignity (and I thought I was immune to political correctness).* The gallery did not allow any photographs to be taken in this exhibition space. The featured banner image is a copy of the cover of the catalogue book written for the exhibition, copied from the Hepworth Wakefield website, accessed on 27/10/2018 at: www.hepworthwakefield.org/whats-on/lee-miller-and-surrealism-in-britain/