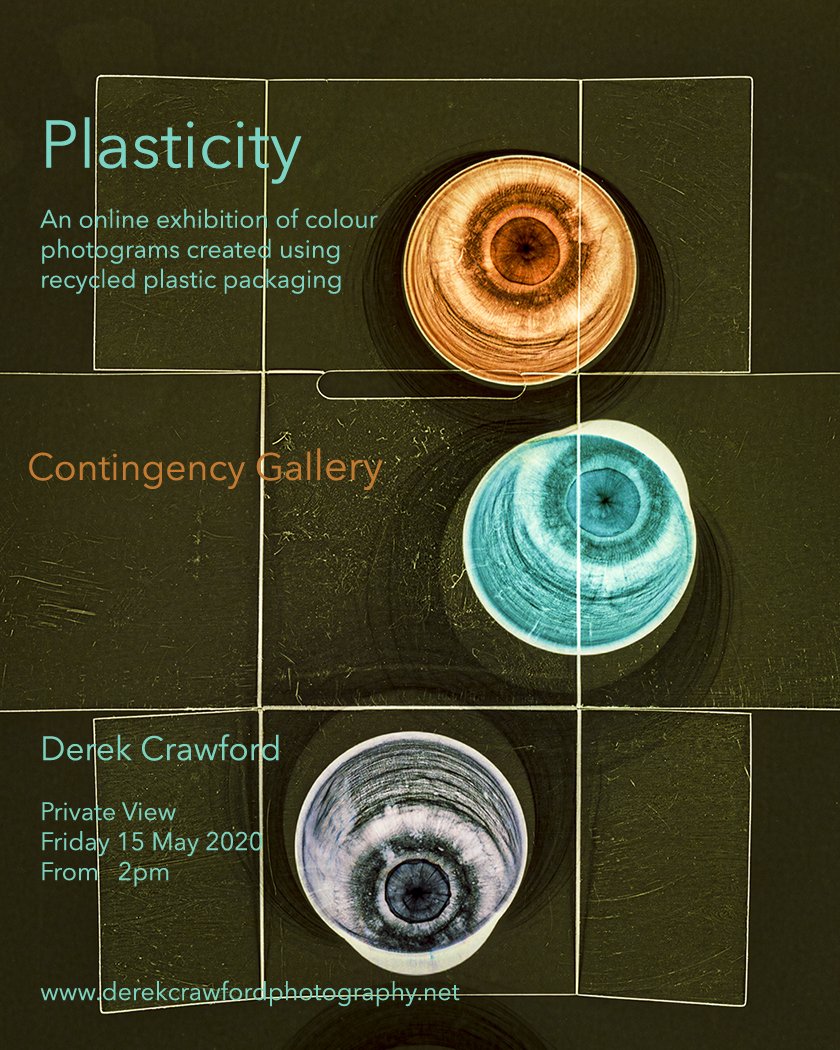

The spread of the Corona Virus epidemic in the UK in March 2019, with the ensuing government enforced social distancing measures and restrictions on movement and association, resulted in the effective lockdown of many public places including educational establishments, council buildings and galleries. This led in turn to the cancellation of our planned end of year exhibition - which would have formed the basis of the submission for our Final Major Project module to complete the requirements of my BA Degree in Photography at Coleg Llandrillo in North Wales.I found it impossible to dispel my deep conviction that a physical print format would be the most appropriate way to present the particular body of work, a series of colour photograms made using the contents of my recycle bin. To resolve this dilemma I decided to build a personal gallery space as a 1 in 12 scale maquette in which to exhibit physical prints, as originally planned. The exhibition is called PLASTICITY and can be viewed on my portfolio website at http://www.derekcrawfordphotography.net or using the direct link to a You Tube Video at youtube.com/watch?v=g-rnFbcAeXg

Garry Fabian Miller: SSHoP Annual Lecture

The presenter of the Annual Lecture of the Scottish Society for the History of Photography (SSHoP) at the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh on 15th November 2019, was the contemporary fine art photographer Garry Fabian Miller. His presentation lasted just over one hour in which he described his career to date in detail including his family background, influences, a brief description of his early social documentary and landscape work, the thinking behind his switch in 1984 to camera-less photography, his current working practice and his collaborations with other artists, writers, poets and musicians.Born in 1957 to parents who ran (and lived in) a long established family studio photography business in Bristol, he was immersed in the atmosphere of the darkroom from early childhood. As a teenager his ambition was to become a 'serious' photographer, at a time when this effectively equated with social documentary photography. His first significant project as a teenager, influenced by the work of Paul Strand in the Outer Hebrides, involved at the age of sixteen, spending the summer of 1973 in the Shetland Islands, living with and documenting the lives of crofters and their families. Several of these images featured in the lecture and this experience of the cycles of rural life in remote wild places, has been a major influence on his life and work since then.A singular feature of his practice has been his use of Cibachrome paper and the dedicated chemistry required to process it, to produce all of his images since 1976. This dye destruction paper, designed as a reversal process for producing direct positive prints from colour transparencies, was known for its distinctively vivid but true to life colour palette, strikingly high gloss almost metallic surface finish and exceptional archival stability. Fabian Miller found that with long enough exposures, he was able to use this paper instead of film in a 10x8 inch large format camera, to photograph seascapes of the Severn Estuary from an attic window in his home. This resulted in 'Sections of England: The Sea Horizon' his first major work, which was first shown in 1977 in the Serpentine Gallery in London and formed the basis of his first solo exhibition in the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol in 1979.He moved to live in a farm in Lincolnshire in 1980 and having developed an interest in Land Art, he transformed a barn into a small gallery, where he met and showed the work of among others Hamish Fulton, Andy Goldsworthy, David Nash, Marie Yates and Roger Ackling. In 1984 he started experimenting with the use of semi-translucent natural materials, grasses, leaves, seed heads and flower petals, placed in the negative carrier of his enlarger and exposed onto Cibachrome paper to make photographs direct from life. By the following year he had decided at the age of 25, that he no longer needed a camera. He made several seasonally based series of images, documenting the sequential changes in the colour of leaves as the chlorophyl levels changed over a period of weeks and several of these are now in the permanent collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.In 1989 he moved with his family to Dartmoor, designed and built a studio with his darkroom at the bottom of their large garden, where he estimates he has spent at least fifty per cent of his waking hours ever since. In around 1992 he virtually stopped using plant materials having developed a technique for projecting beams of light, filtered through glass vessels containing coloured oils and liquids, directly onto photosensitive paper, with only small pieces of card placed in the light path to produce the geometric shapes in his photographs. His work has become progressively more abstract and since 2017, he has experimented with using additional small light sources, for example burning matches, to produce localised bright highlights mimicking the appearance of flames. His daily routine also involves walking , either in the early morning or the evening, taking inspiration in the special auras of light in the skies and the colours this produces in the blossoms of the vegetation, along with the atmosphere of the ancient archeological sites and burial cairns on the surrounding moorland, which he tries to represent in his work. Although most of his work has been made in his own darkroom, he has made some images on visits to the islands of Tiree, off the West coast of Scotland, Skellig Michael and Inis Meain (one of the Aran Islands), both off the West coast of Ireland. He described Inis Meain as one of the last bastions of purity in Ireland, a view shared by the artist Sean Scully, who made one of his few books of photographs on the island. While Fabian Miller always works alone in his darkroom, when it comes to distributing his work he has collaborated extensively with other artists including writers, poets, musicians, potters, weavers and curators. One of his most important collaborations over the years has been with Martin Barnes, the curator of Photography at the V&A Museum, who has aquired his work for their collection, wrote an introduction to one of his books, curated his 2005 exhibition at the V&A and included his work in the major retrospective exhibition of camera-less photography, 'Shadow Catchers' also at the V&A in 2011. Several other authors have also contributed to sections in his books, including Marina Warner, Nigel Warburton and Adam Nicolson (The Colour of Time, 2010) and the author and ceramicist Edmund de Waal with the poet Alice Oswald (Blaze, 2019). Alice Oswald has also collaborated in live performances of his work along with her poetry as has the cellist and composer Oliver Coates. Since 2013, Fabian Miller has also worked with the weavers in the Dovecot Studio in Edinburgh, making gun tufted rugs (some of which have been acquired by the Standard Life Aberdeen Investment Bank for the foyer of their Edinburgh Head Office - see photograph above) and in 2017 a tapestry, based on the colours and shapes in his photographs. Probably his most important collaboration over the last ten years has been with John Bodkin a master of digital printing who has helped in the challenging process of colour correcting high resolution scans of Fabian Miller's Cibachrome prints, while trying to maintain as closely as possible the subtleties of their original appearance and surface. This allows them to be re-printed to archival standards as 'C'prints using the Lambda Lightjet printing system, for exhibition at a much larger scale. Some of these prints were recently exhibited at the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh who have also worked closely with Fabian Miller for many years (see previous post from 16 Dec 2019).Moving into the third decade of the 21st century, it is relatively unusual to find an internationally acclaimed photographer whose primary method of creating images is so completely dependent on a traditional wet darkroom process. This is all the more surprising on discovering that no Cibachrome papers have been manufactured since 2012. Cibachrome papers are relatively stable if correctly stored (in a freezer) and Fabian Miller had the foresight to stock up when the last batch was produced. This supply is running out and he is down to his last one hundred sheets. There may be a few individuals around the world who still have small stocks in storage but they are unlikely to become available and their archival status will be unpredictable. The Cibachrome process chemistry is if anything more difficult to store and although there are possible work arounds using monochrome developers and RA4 process bleach/fix, he has decided that when he completes his current project using his remaining stock, he will close his darkroom forever. A very well written account of the saga of the demise of Cibachrome/Ilfochrome is available online (Vincent 2018).Under the circumstances, Fabian Miller seems remarkably optimistic about the future. He has a large library of work already made and now has access to the skills required to work with this digitally. He stopped selling his Cibachrome originals some time ago to retain them for future projects and now only sells his work as Lambda Lightjet 'C'prints. Although his work has can appear very precise and controlled, his almost poetic relationship with the elemental forces which shape his connection to the land are still very apparent. He discovered very recently that the building in Bristol in which he had been brought up, was at one time owned by the publisher Joseph Cottle. In one of their well documented walking tours in the 1790's, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, stayed for several days with Cottle in Bristol, before crossing the Severn by ferry to travel up the Wye Valley to Tintern. It transpires that Dorothy Wordsworth slept in the bedroom, which in later years became the darkrooom in which he still remembers playing as a child, while his parents were printing their work. He is currently trying to work out if there is a way of using this in the generation of his next project.The importance of the darkroom and its role in the history of the photography which so dramatically transformed our interactions with the rest of the world, can perhaps only be fully appreciated by those who have experienced working in one. In an attempt to address this, Historic England spent several days with Fabian Miller in 2016, documenting his working process. He has also made arrangements with the V&A Museum that when he does close his darkroom, it will be dismantled and installed in their Photography section as a new exhibit for visitors to experience. His archive of darkroom notebooks will also be acquired by the museum to be made available to future researchers.In discussion following the lecture, he was asked if his experience of the demise of Cibachrome felt like coming to the end of a prolonged terminal illness. While agreeing that the end of Cibachrome was sad, he feels that the potential of digital photography is exciting and that it is probably still in its infancy, with much still to be explored. He feels that it is important that people understand that the invention of chemical photography was a seminal moment in world history and is encouraged by the fact that there are still people who are trying to keep it alive. He has been thinking for some time about the early experiments of Fox Talbot and his correspondence with John Herschel, wondering if there is any scope for further research into this source material for clues as to developing other new processes. Examples of Fabian Miller's work and links to interviews with him are available at the websites of the V&A Museum, the Ingleby Gallery and on his own site, at www.garryfabianmiller.com. Barnes M. and Fabian Miller G. (2005) 'Illumine'. Merell Publishing London.Barnes M. (2012) 'Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography'. Merell Publishing London.Fabian Miller G. (2010) 'The Colour of Time'. Black Dog Publishing, London.Fabian Miller G. (2019) 'Blaze" Ingleby, Edinburgh.Scully S (2007) 'The Walls of Aran' Thames and Hudson, London.https://www.inglebygallery.com/artists/51-garry-fabian-miller/overview/https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/garry-fabian-miller

Since 2013, Fabian Miller has also worked with the weavers in the Dovecot Studio in Edinburgh, making gun tufted rugs (some of which have been acquired by the Standard Life Aberdeen Investment Bank for the foyer of their Edinburgh Head Office - see photograph above) and in 2017 a tapestry, based on the colours and shapes in his photographs. Probably his most important collaboration over the last ten years has been with John Bodkin a master of digital printing who has helped in the challenging process of colour correcting high resolution scans of Fabian Miller's Cibachrome prints, while trying to maintain as closely as possible the subtleties of their original appearance and surface. This allows them to be re-printed to archival standards as 'C'prints using the Lambda Lightjet printing system, for exhibition at a much larger scale. Some of these prints were recently exhibited at the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh who have also worked closely with Fabian Miller for many years (see previous post from 16 Dec 2019).Moving into the third decade of the 21st century, it is relatively unusual to find an internationally acclaimed photographer whose primary method of creating images is so completely dependent on a traditional wet darkroom process. This is all the more surprising on discovering that no Cibachrome papers have been manufactured since 2012. Cibachrome papers are relatively stable if correctly stored (in a freezer) and Fabian Miller had the foresight to stock up when the last batch was produced. This supply is running out and he is down to his last one hundred sheets. There may be a few individuals around the world who still have small stocks in storage but they are unlikely to become available and their archival status will be unpredictable. The Cibachrome process chemistry is if anything more difficult to store and although there are possible work arounds using monochrome developers and RA4 process bleach/fix, he has decided that when he completes his current project using his remaining stock, he will close his darkroom forever. A very well written account of the saga of the demise of Cibachrome/Ilfochrome is available online (Vincent 2018).Under the circumstances, Fabian Miller seems remarkably optimistic about the future. He has a large library of work already made and now has access to the skills required to work with this digitally. He stopped selling his Cibachrome originals some time ago to retain them for future projects and now only sells his work as Lambda Lightjet 'C'prints. Although his work has can appear very precise and controlled, his almost poetic relationship with the elemental forces which shape his connection to the land are still very apparent. He discovered very recently that the building in Bristol in which he had been brought up, was at one time owned by the publisher Joseph Cottle. In one of their well documented walking tours in the 1790's, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, stayed for several days with Cottle in Bristol, before crossing the Severn by ferry to travel up the Wye Valley to Tintern. It transpires that Dorothy Wordsworth slept in the bedroom, which in later years became the darkrooom in which he still remembers playing as a child, while his parents were printing their work. He is currently trying to work out if there is a way of using this in the generation of his next project.The importance of the darkroom and its role in the history of the photography which so dramatically transformed our interactions with the rest of the world, can perhaps only be fully appreciated by those who have experienced working in one. In an attempt to address this, Historic England spent several days with Fabian Miller in 2016, documenting his working process. He has also made arrangements with the V&A Museum that when he does close his darkroom, it will be dismantled and installed in their Photography section as a new exhibit for visitors to experience. His archive of darkroom notebooks will also be acquired by the museum to be made available to future researchers.In discussion following the lecture, he was asked if his experience of the demise of Cibachrome felt like coming to the end of a prolonged terminal illness. While agreeing that the end of Cibachrome was sad, he feels that the potential of digital photography is exciting and that it is probably still in its infancy, with much still to be explored. He feels that it is important that people understand that the invention of chemical photography was a seminal moment in world history and is encouraged by the fact that there are still people who are trying to keep it alive. He has been thinking for some time about the early experiments of Fox Talbot and his correspondence with John Herschel, wondering if there is any scope for further research into this source material for clues as to developing other new processes. Examples of Fabian Miller's work and links to interviews with him are available at the websites of the V&A Museum, the Ingleby Gallery and on his own site, at www.garryfabianmiller.com. Barnes M. and Fabian Miller G. (2005) 'Illumine'. Merell Publishing London.Barnes M. (2012) 'Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography'. Merell Publishing London.Fabian Miller G. (2010) 'The Colour of Time'. Black Dog Publishing, London.Fabian Miller G. (2019) 'Blaze" Ingleby, Edinburgh.Scully S (2007) 'The Walls of Aran' Thames and Hudson, London.https://www.inglebygallery.com/artists/51-garry-fabian-miller/overview/https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/garry-fabian-miller

Vincent D (2018) A Brief History of Cibachrome Online at: https://douglasvincent.com/ilfochrome/history.html Accessed 11 February 2020

Butte de Montmartre, Paris.

The 'Basilique du Sacre Coeur de Montmartre' which dominates the skyline in the north of Paris is one of the most popular tourist attractions in the city and is undeniably impressive, especially when floodlit at night. While the Romano-Byzantine architectural features used in Paul Abadie's design suggest it could be much older, building started in 1875 and it was not completed until 1914 (though following the outbreak of the First World War, was not consecrated until 1919). The 'hill of the martyrs' was used as a site of worship by the Druids of ancient Gaul as well as the Romans and was documented as the site of the marytrdom of Saint Denis the first bishop of Paris in a history of the life of Saint Genevieve in 475AD. The last of several earlier churches had been destroyed a hundred years earlier following the French Revolution and the new basilica was commissioned following a 'vow of reparation' instigated by the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul, following the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 with subsequent occupation by the German Army.For my trip to Paris Photo, the 'most affordable' hotel I could find within walking distance of the Gare du Nord, happened to be around the corner from where I made the photograph of Sacre Coeur above, in the Butte de Montmartre (the area around the bottom of the steps leading up to the Basilica). My first impression, that this was not one of the more well maintained parts of the city, was confirmed the following morning, when I opened the curtains of my room in the ironically named Hotel Bellevue. Unfortunately I did not have time to explore the more gentrified areas of Montmartre and did not get to the famous cemetery where several of the artists and poets who lived here are buried. There was however plenty to photograph in the narrow streets around the hotel, mainly cafes, restaurants, shops selling tatty tourist souvenirs and for some reason, all sorts of fabrics, most of which appeared to have been sourced from the middle east.

Unfortunately I did not have time to explore the more gentrified areas of Montmartre and did not get to the famous cemetery where several of the artists and poets who lived here are buried. There was however plenty to photograph in the narrow streets around the hotel, mainly cafes, restaurants, shops selling tatty tourist souvenirs and for some reason, all sorts of fabrics, most of which appeared to have been sourced from the middle east.

The area appears to have been undergoing extensive change and the streets are starting in places to look quite shabby with a lot of graffiti - one of the few things that perhaps point to the area having an artistic heritage.

The area appears to have been undergoing extensive change and the streets are starting in places to look quite shabby with a lot of graffiti - one of the few things that perhaps point to the area having an artistic heritage.

In the daytime the steps leading up to Sacre Coeur quickly get very crowded, negating any sense of reverence for a site created for the purpose of religious devotion. This is exacerbated by the number of unlicensed street vendors trying to make a living by selling any number of cheap shiny plastic trinkets, predominantly Eiffel Towers and religious statuettes. The wider terraces are also populated with acrobatic breakdancing buskers using portable amplifiers and beat-boxes, a potential magnet for pick-pockets.

In the daytime the steps leading up to Sacre Coeur quickly get very crowded, negating any sense of reverence for a site created for the purpose of religious devotion. This is exacerbated by the number of unlicensed street vendors trying to make a living by selling any number of cheap shiny plastic trinkets, predominantly Eiffel Towers and religious statuettes. The wider terraces are also populated with acrobatic breakdancing buskers using portable amplifiers and beat-boxes, a potential magnet for pick-pockets.

In recent years, civil unrest and anti-government protests have featured prominently in news reports from France and the 'gilets jaunes' were in the process of setting up a small demonstration when I arrived, closely observed from a discrete distance by the police.

In recent years, civil unrest and anti-government protests have featured prominently in news reports from France and the 'gilets jaunes' were in the process of setting up a small demonstration when I arrived, closely observed from a discrete distance by the police.

That was when by pure chance, I arrived at the Halle Saint Pierre with a sign for an exhibition of photographs and artworks by Roger Ballen and I knew then what I was going to be doing for the rest of the morning.http://www.sacre-coeur-montmartre.com/english/

That was when by pure chance, I arrived at the Halle Saint Pierre with a sign for an exhibition of photographs and artworks by Roger Ballen and I knew then what I was going to be doing for the rest of the morning.http://www.sacre-coeur-montmartre.com/english/

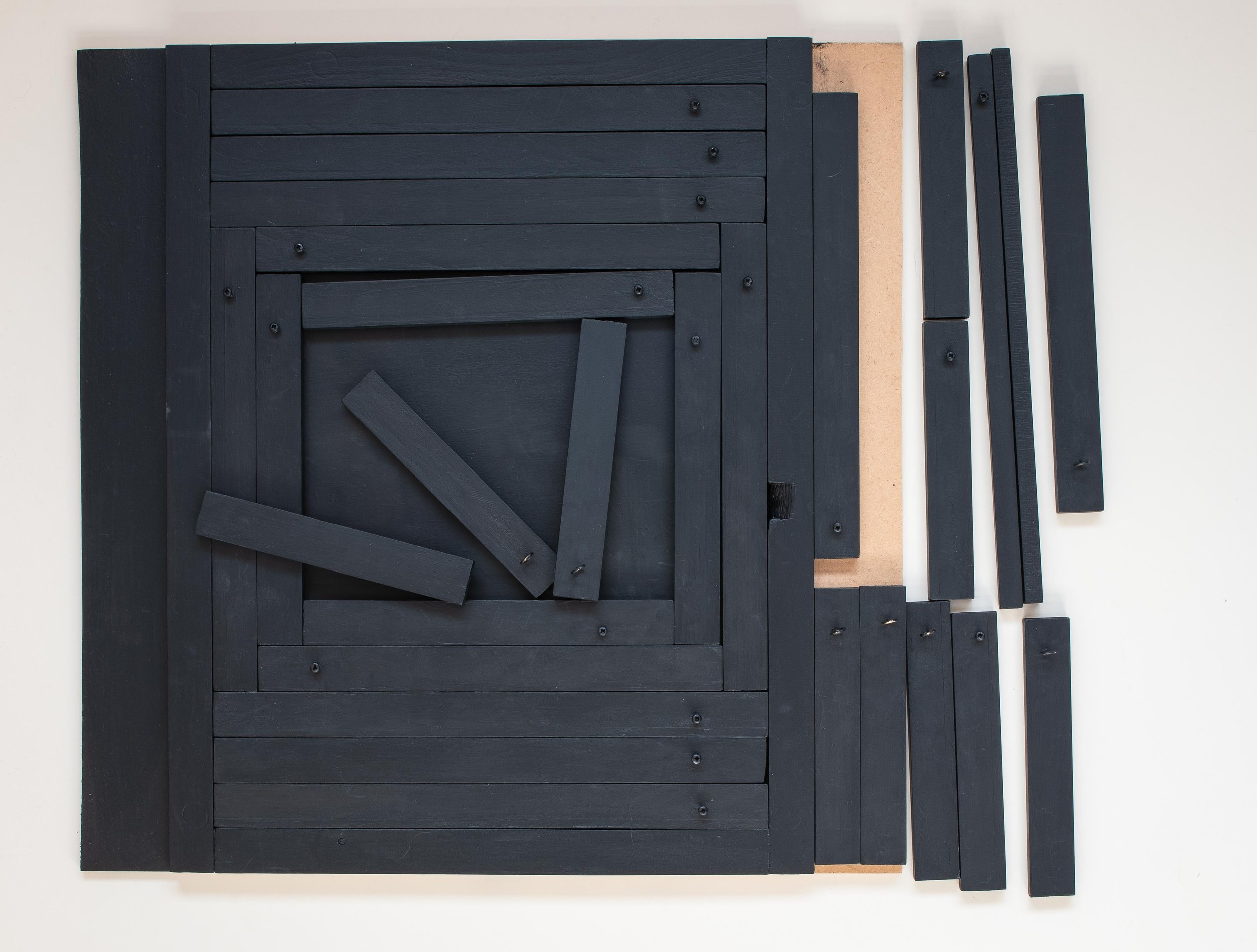

A masking frame for photograms

The challenge of accurate alignment of objects on a sheet of colour photographic paper and masking areas for multiple different exposures in total darkness, demands the assistance of a suitable tool for the job. Commercially available darkroom masking frames are designed perfectly to hold a single sheet of paper flat but have no mechanism for ensuring the precise location of three dimensional objects or re-positioning them for further exposures. I felt this called for a tray design, with shallow sides and removable blocks of different sizes to create the spacing for the commonly available colour print papers I use, 16 x 12 in., 12 x 9.5in and 10 x 8 in. The design I came up with used a sheet of MDF and strips of 10mm thick and 25mm (approximating to 1 inch) wide timber cut to several lengths and painted matt black to minimise reflections. The outer fixed strips have been fixed with adhesive to create a base with internal dimension of 16 x 12 inches. The inner removable strips vary in size from 6 to 12 inches in length, with one 12 inch strip halved lengthwise for the 9.5 inch paper. One inch is more precisely 25.3mm and allowing for the thickness of two coats of paint (and my very limited woodworking skill-set), the jigsaw of pieces fits together reasonably efficiently. A few small gaps are inevitable however and stray narrow shafts of light should get through unpredictably frequently enough to leave room for serendipity to have an effect. The paintwork needs a few more days to harden and then it will be time to get back in the darkroom to find out how well it works.

One inch is more precisely 25.3mm and allowing for the thickness of two coats of paint (and my very limited woodworking skill-set), the jigsaw of pieces fits together reasonably efficiently. A few small gaps are inevitable however and stray narrow shafts of light should get through unpredictably frequently enough to leave room for serendipity to have an effect. The paintwork needs a few more days to harden and then it will be time to get back in the darkroom to find out how well it works.

A happy accident

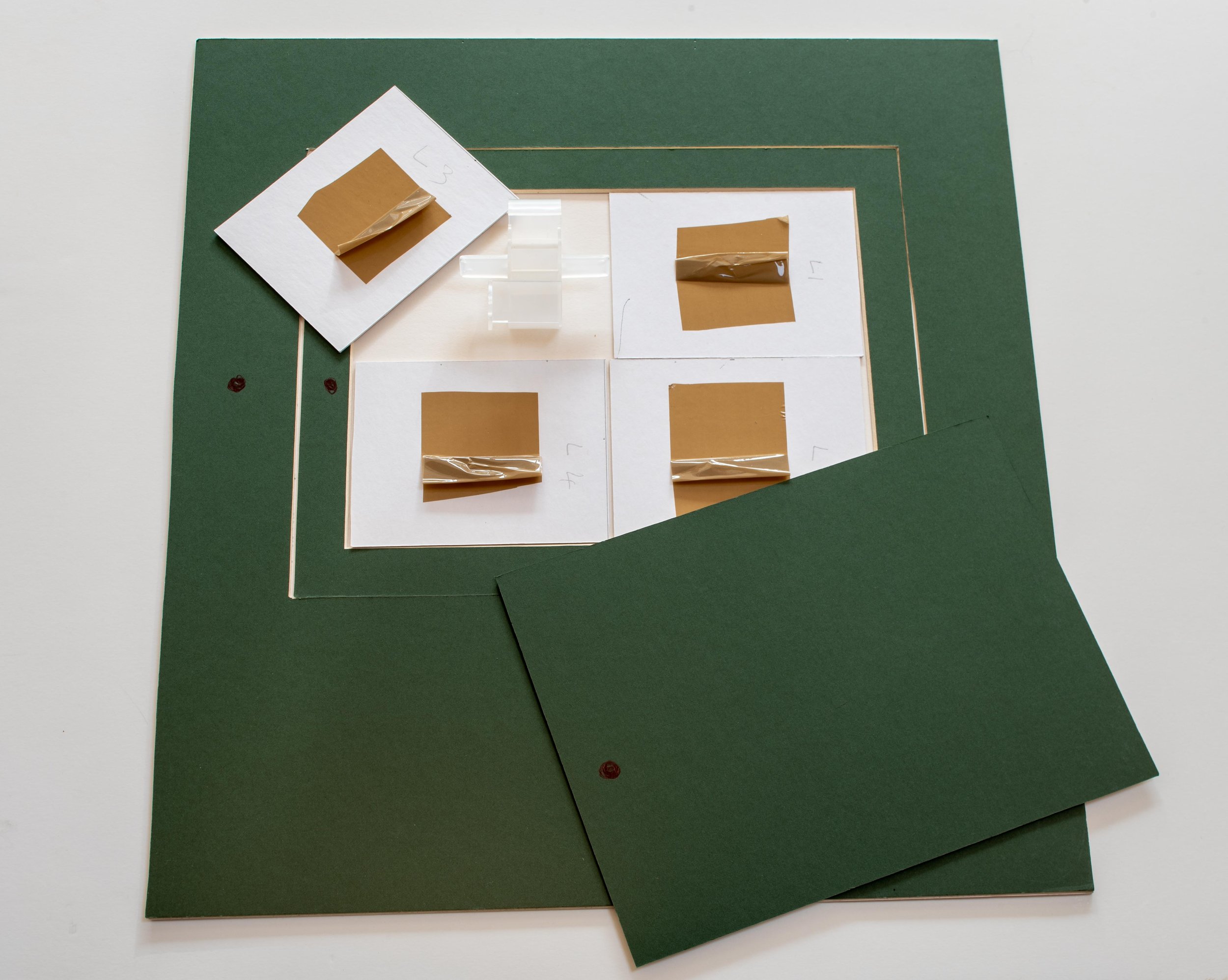

It is expected that a competent photographer should be capable of producing carefully exposed, precisely focused, technically perfect images. Learning the skills set required to master the controls of the camera can lead to a fixation on exposure and sharpness, a constant imperative that this must be done 'correctly', which in turn may constrain the development of personal visual expression (Ulrich, 2018). One way of balancing these conflicting processes, arriving at an equipoise between obsession with technique and freedom of expression, could be to concentrate on the basic elements, defined by Angela Faris Belt as constituting the 'grammar of photographic language'; framing and borders, quality of focus (using lenses and apertures to control depth of field), time and motion (determined by shutter speed) and the physical media used to present the final image (Belt, 2008).Patricia Townsend discusses this in her essay in 'Photographers and Research', stressing the importance of being able to respond to all aspects of the medium (camera, processing of film, digital process, printing technique or darkroom equipment), and then listen to what the medium has to 'say'. In the essay, she quotes photographer Liz Rideal as follows: "it's about the happy accident but it's also about recognising something when it's coming to the surface" (Townsend, 2017). The photogram below could be considered as and example of an accidental discovery arising from the challenge of working with colour photographic paper, which being polychromatic has to be handled in complete darkness. I was attempting to produce an image with a single plastic insert, using a seemingly 'simple' makeshift masking technique with scrap cardboard, to make four separate exposures and create a futuristic grid like structure. I gave up when it proved impossible to align the plastic accurately in the dark and the cardboard masks kept slipping between exposures.

I was attempting to produce an image with a single plastic insert, using a seemingly 'simple' makeshift masking technique with scrap cardboard, to make four separate exposures and create a futuristic grid like structure. I gave up when it proved impossible to align the plastic accurately in the dark and the cardboard masks kept slipping between exposures. On reviewing the dried prints the following morning, I realised that the randomly overlapping placement of the card and the plastic insert had produced different levels of exposure (particularly in the bottom right hand corner), creating unexpected shapes with different tones of the same colour. The resulting image is almost certainly more interesting, than it would have been if the technique had worked 'correctly' and I now know (roughly) how to repeat the effect.Psychoanalysis has identified that the freedom to be creative is dependent on the ability to enter a state of mind which is similar to that found in children (and adults) engaging in uninhibited play (Winnicott, 1971). Is it possible to create these happy accidents or do we have to keep working, trying to find ways around the limitations of our processes and materials and hope that we can recognise them when they eventually come along?Belt A F (2008). 'The Elements of Photography'. Oxford; Focal Press (Elsevier Inc.), p XIX.Townsend P (2017). 'Between Inner and Outer Worlds'. In: Photographers and Research, ed. Read S and Simmons M; Abingdon, Oxon., Focal Press (Routledge). pp 211-212.Ulrich D (2018). 'Zen Camera'; New York, Watson-Guptill Publications, p 140.Winnicott D W (1971). 'Playing and Reality'. Abingdon, Oxon., Routledge. p 71.

On reviewing the dried prints the following morning, I realised that the randomly overlapping placement of the card and the plastic insert had produced different levels of exposure (particularly in the bottom right hand corner), creating unexpected shapes with different tones of the same colour. The resulting image is almost certainly more interesting, than it would have been if the technique had worked 'correctly' and I now know (roughly) how to repeat the effect.Psychoanalysis has identified that the freedom to be creative is dependent on the ability to enter a state of mind which is similar to that found in children (and adults) engaging in uninhibited play (Winnicott, 1971). Is it possible to create these happy accidents or do we have to keep working, trying to find ways around the limitations of our processes and materials and hope that we can recognise them when they eventually come along?Belt A F (2008). 'The Elements of Photography'. Oxford; Focal Press (Elsevier Inc.), p XIX.Townsend P (2017). 'Between Inner and Outer Worlds'. In: Photographers and Research, ed. Read S and Simmons M; Abingdon, Oxon., Focal Press (Routledge). pp 211-212.Ulrich D (2018). 'Zen Camera'; New York, Watson-Guptill Publications, p 140.Winnicott D W (1971). 'Playing and Reality'. Abingdon, Oxon., Routledge. p 71.

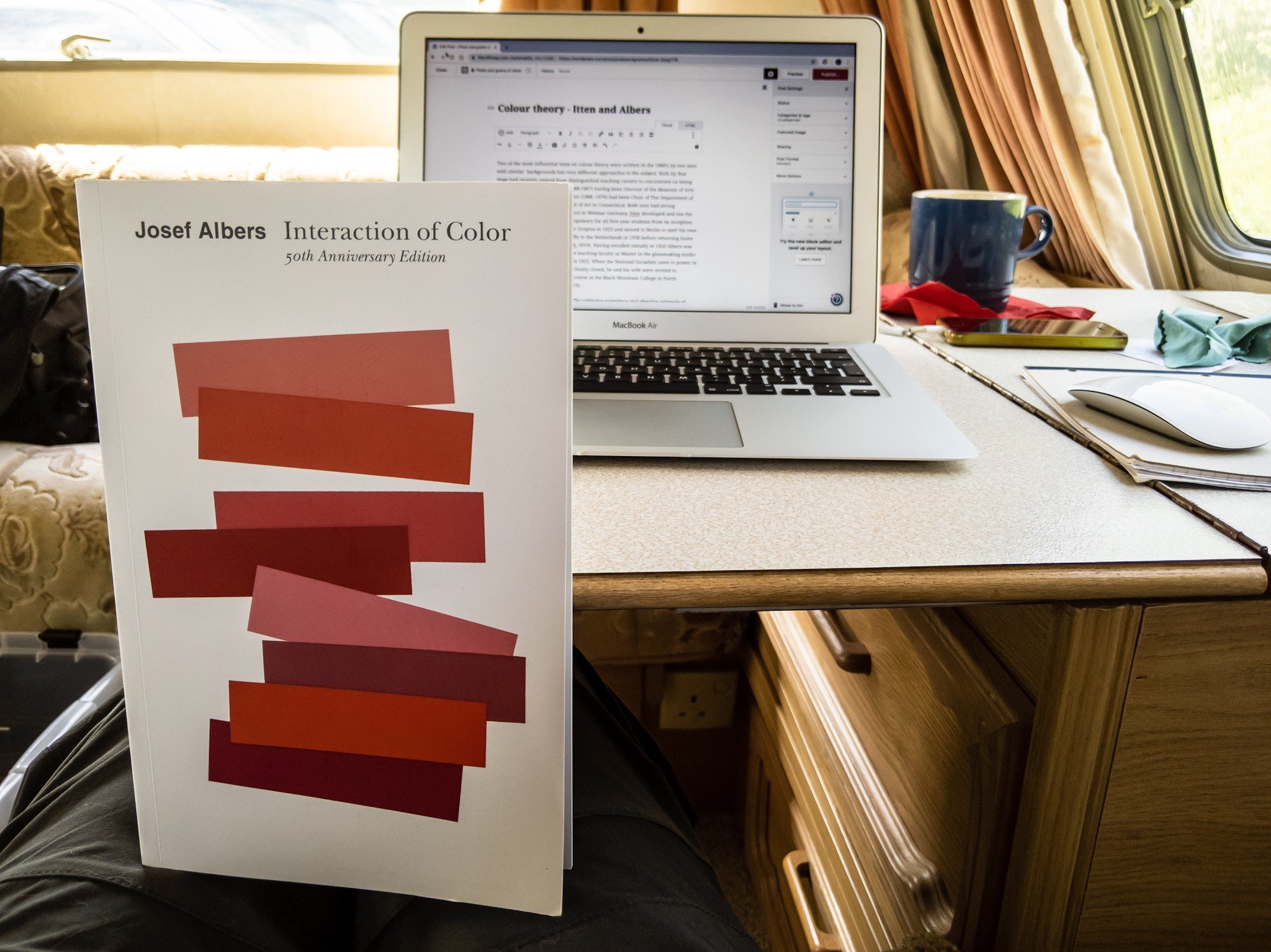

Colour theory - Itten and Albers

Two of the most influential texts on colour theory were written in the 1960's by two men with similar backgrounds but very different approaches to the subject. Both by that stage had recently retired from distinguished teaching careers to concentrate on being working artists, Johannes Itten (1888-1967) having been Director of the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zurich and Josef Albers (1888 -1976), Chair of The Department of Design at the Yale University School of Art in Connecticut. Both men had strong connections with the Bauhaus School in Weimar Germany. Itten developed and ran the Preliminary Course which was compulsory for all first year students from its inception in 1919 until he fell out with Walter Gropius in 1923 and moved to Berlin to start his own school of design. He moved briefly to the Netherlands in 1938 before returning home to Switzerland later that year (Art Directory Gmbh, 2019). Having enrolled initially in 1920 Albers was the first Bauhaus student to join the teaching faculty as a Master in the glassmaking studio, at the time the school moved to Dessau in 1925. When the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933 and the Bauhaus finally closed, he and his wife were invited to establish the inaugural visual arts course at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina (albersfoundation.org, 2019).  On first impression Art of Color : The subjective experience and objective rationale of color by Johannes Itten has the look and feel of a beautifully illustrated traditional large format textbook. The early chapters explain colour physics, with brief descriptions of the colour spectrum, the light forming wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation which are focused via the optical mechanism of the eye (cornea and lens) to be captured by the photosensitive cells in the retina (the sensor), then transmitted to the optical cortex of the brain to be perceived as a continually refreshed image. Subsequent chapters move on from these objective principles to his own theories (expanding on earlier work by Adolf Holzel with whom he had trained in Stuttgart), which explore how our subjective perception can be influenced by emotional and symbolic factors in combination with the visual interactions of complementary and contrasting colours (bauhaus100.com, 2019). "Color perception is the psycho-physiological reality as distinguished from the physio-chemical reality of color" (Itten, 1963). His explanations of the significance of these phenomena are illustrated by reference to a series of paintings ranging chronologically from eighth century religious paintings, through the work of the European old masters, to the abstract modern art of Klee (a fellow Master in the Bauhaus teaching faculty), Mondrian and Picasso. The book is worth reading for these comprehensive insightful explanations alone.The approach taken by Albers in the more modest looking Interaction of Color is that of a practical course manual for students in a colour theory classroom, presented as a series of exercises using swatches of coloured papers, designed to demonstrate rather than simply describe how interacting colours are perceived. The illustrations linked to each chapter are presented separately from the exercises, the aim being that students should first try to reproduce them for themselves, presumably as a more effective way of learning. Many of the exercises recreate apparent optical illusions (colour deceptions) but in doing so, provide rational explanations for complex phenomena and like Itten, demonstrating that "in visual perception there is a discrepancy between physical fact and psychic effect" (Albers, 1963). His demonstrations of the use of the effect of colour intensity (brightness) to show how an identical swatch of colour is perceived differently depending on the background it is placed against (page 8) and the phenomenon of the after image (page 22) are simple but remarkably effective.

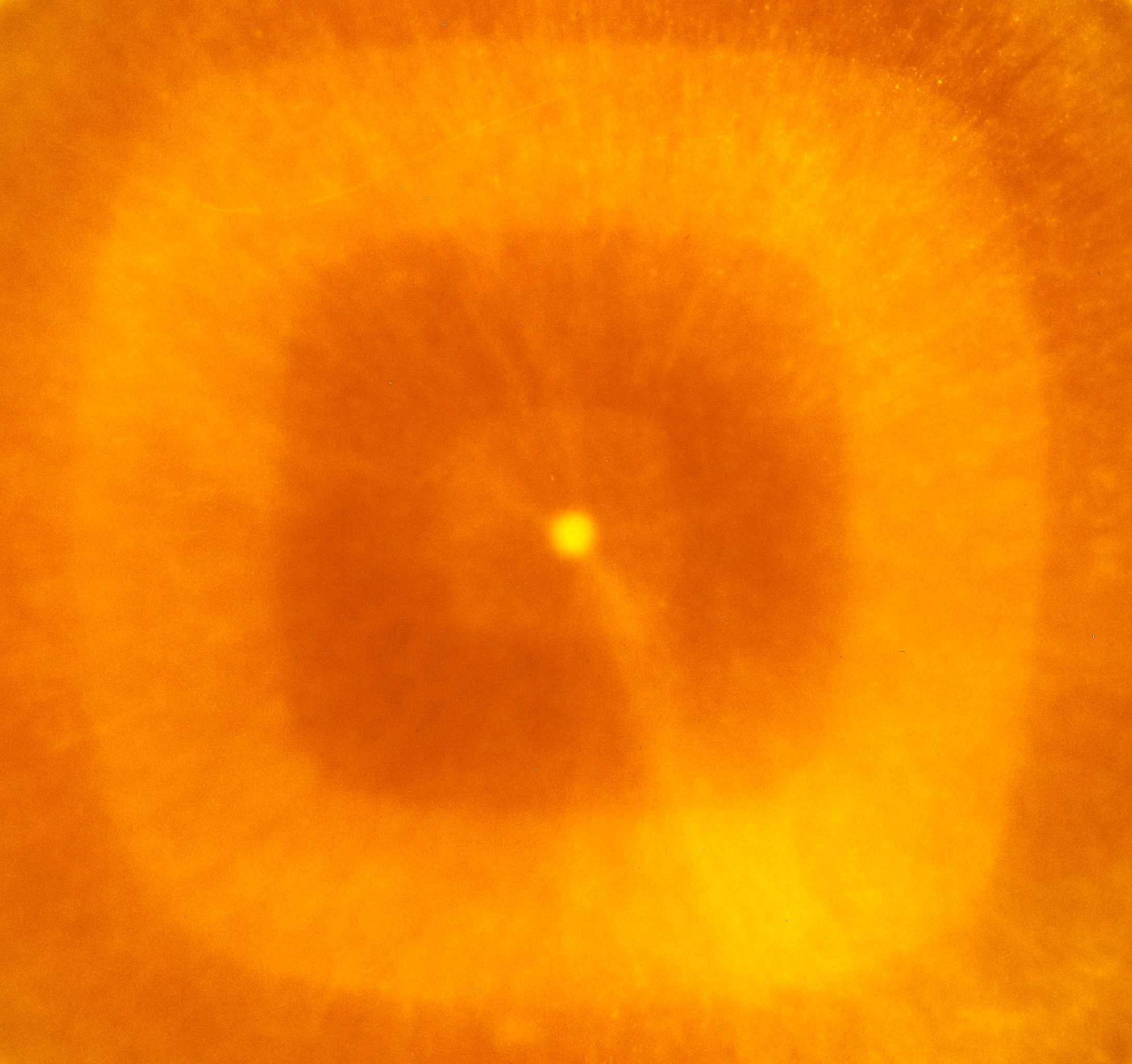

On first impression Art of Color : The subjective experience and objective rationale of color by Johannes Itten has the look and feel of a beautifully illustrated traditional large format textbook. The early chapters explain colour physics, with brief descriptions of the colour spectrum, the light forming wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation which are focused via the optical mechanism of the eye (cornea and lens) to be captured by the photosensitive cells in the retina (the sensor), then transmitted to the optical cortex of the brain to be perceived as a continually refreshed image. Subsequent chapters move on from these objective principles to his own theories (expanding on earlier work by Adolf Holzel with whom he had trained in Stuttgart), which explore how our subjective perception can be influenced by emotional and symbolic factors in combination with the visual interactions of complementary and contrasting colours (bauhaus100.com, 2019). "Color perception is the psycho-physiological reality as distinguished from the physio-chemical reality of color" (Itten, 1963). His explanations of the significance of these phenomena are illustrated by reference to a series of paintings ranging chronologically from eighth century religious paintings, through the work of the European old masters, to the abstract modern art of Klee (a fellow Master in the Bauhaus teaching faculty), Mondrian and Picasso. The book is worth reading for these comprehensive insightful explanations alone.The approach taken by Albers in the more modest looking Interaction of Color is that of a practical course manual for students in a colour theory classroom, presented as a series of exercises using swatches of coloured papers, designed to demonstrate rather than simply describe how interacting colours are perceived. The illustrations linked to each chapter are presented separately from the exercises, the aim being that students should first try to reproduce them for themselves, presumably as a more effective way of learning. Many of the exercises recreate apparent optical illusions (colour deceptions) but in doing so, provide rational explanations for complex phenomena and like Itten, demonstrating that "in visual perception there is a discrepancy between physical fact and psychic effect" (Albers, 1963). His demonstrations of the use of the effect of colour intensity (brightness) to show how an identical swatch of colour is perceived differently depending on the background it is placed against (page 8) and the phenomenon of the after image (page 22) are simple but remarkably effective. I am working my way through both of these books at present and am only just beginning to get to get to grips with the subject. The featured image below is my digital photograph of a step in a bathroom ceiling which is painted entirely white.

I am working my way through both of these books at present and am only just beginning to get to get to grips with the subject. The featured image below is my digital photograph of a step in a bathroom ceiling which is painted entirely white. The colours have been produced through manipulation of the RAW file in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, simply by accentuating (albeit grossly) the existing colour casts in the image. The sunlit area is warm in tone, producing the primary colour yellow when enhanced, while the tone of the area in shadow is cool forming the complementary blue when accentuated. These casts are barely perceptible in the original photograph and not normally 'seen' by the naked eye as, knowing that the paint is white, our brain 'corrects' this for us. Photographers working in colour, in trying to obtain colours which are true to life, usually correct these casts when they become apparent. This experiment for me suggests that in reality the colours are already there, which would mean that in striving to obtain tones which will be perceived as 'true', we may in fact be perpetrating a deception. Albers J (1963). 'Interaction of Color'. New Haven, Yale University Press. (My edition of this is the Fiftieth Anniversary (4th) Edition of the paperback version, still in print and published in 2013)albersfoundation.org (2019). Josef and Anni Albers biographies. Online, Accessed 27 April, 2019 at: www.albersfoundation.org/artists/biographies/Art Directory Gmbh (2019). Johannes Itten Biography. Online, Accessed 2 May, 2019 at: www.johannes-itten.combauhaus100.com (2019) Johannes Itten. Online, Accessed 2 May 2019 at: https://www.bauhaus100.com/the-bauhaus/people/masters-and-teachers/johannes-itten/Itten J (1973) 'Art of Color : The subjective experience and objective rationale of color'. New York, John Wiley and Sons Inc. (first published in Germany in 1961 by Otto Maier Verlag)

The colours have been produced through manipulation of the RAW file in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, simply by accentuating (albeit grossly) the existing colour casts in the image. The sunlit area is warm in tone, producing the primary colour yellow when enhanced, while the tone of the area in shadow is cool forming the complementary blue when accentuated. These casts are barely perceptible in the original photograph and not normally 'seen' by the naked eye as, knowing that the paint is white, our brain 'corrects' this for us. Photographers working in colour, in trying to obtain colours which are true to life, usually correct these casts when they become apparent. This experiment for me suggests that in reality the colours are already there, which would mean that in striving to obtain tones which will be perceived as 'true', we may in fact be perpetrating a deception. Albers J (1963). 'Interaction of Color'. New Haven, Yale University Press. (My edition of this is the Fiftieth Anniversary (4th) Edition of the paperback version, still in print and published in 2013)albersfoundation.org (2019). Josef and Anni Albers biographies. Online, Accessed 27 April, 2019 at: www.albersfoundation.org/artists/biographies/Art Directory Gmbh (2019). Johannes Itten Biography. Online, Accessed 2 May, 2019 at: www.johannes-itten.combauhaus100.com (2019) Johannes Itten. Online, Accessed 2 May 2019 at: https://www.bauhaus100.com/the-bauhaus/people/masters-and-teachers/johannes-itten/Itten J (1973) 'Art of Color : The subjective experience and objective rationale of color'. New York, John Wiley and Sons Inc. (first published in Germany in 1961 by Otto Maier Verlag)

Royal College of Art : Colour Reference Library

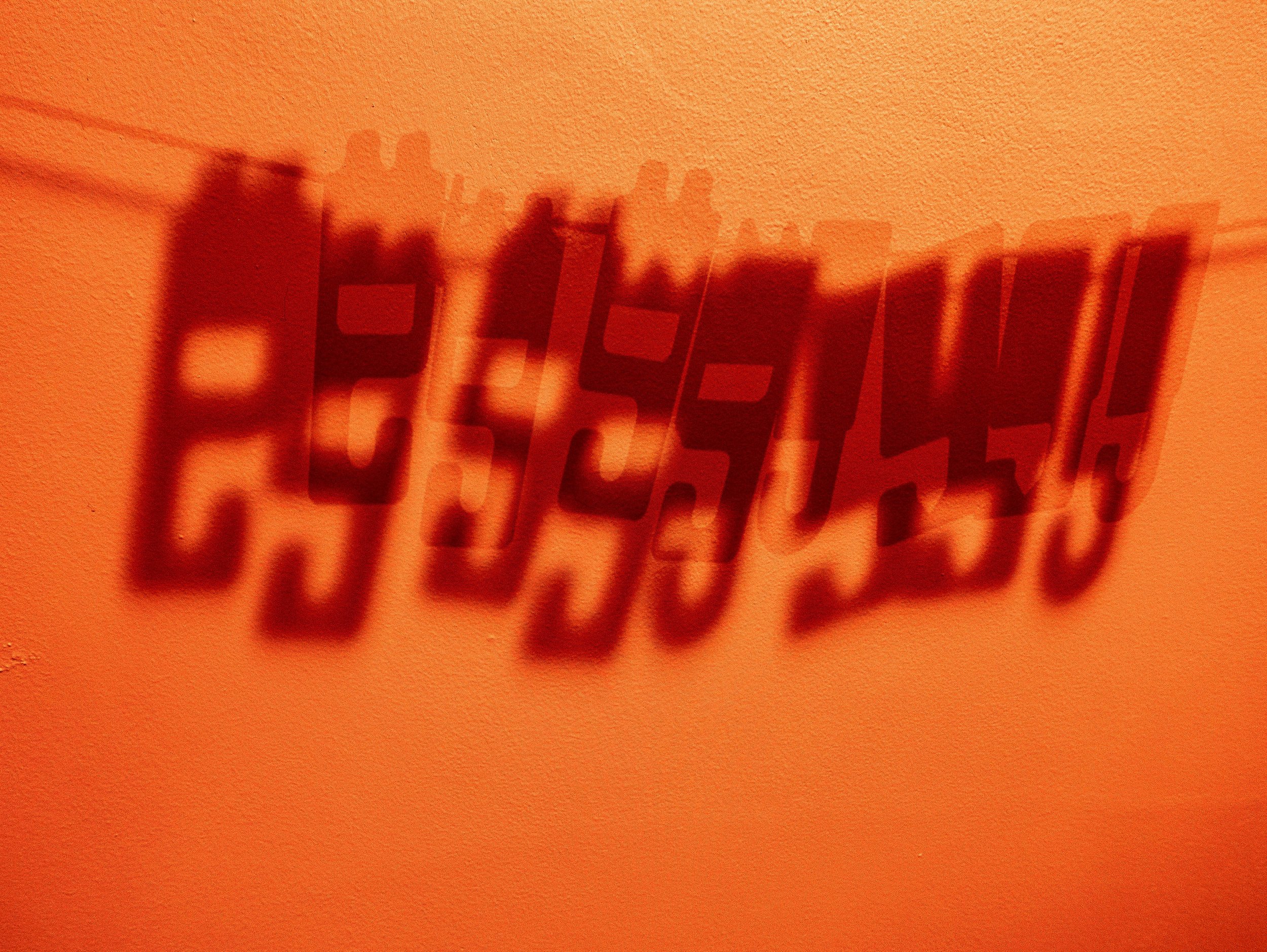

For future reference - a useful link for potential access to primary and secondary research material on colour theory. According to the RCA website it is 'one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of colour-related materials in the world', covering art, science, theory and practice and consisting of books, pamphlets, colour swatches and journals. In the oversize collection, they have a copy of Josef Albers' Interaction of Color, in its original edition from 1963 with full size silk-screen plates.RCA Special Collections is housed in a purpose built archival storage storage facility with a temperature controlled environment, on the top floor of the Library in the Common Room Block of the Royal College of Art, Kensington Gore, London, SW7 2EU. Access is open to all bona fide researchers (I.D. required) by appointment only through email at special-collections@rca.ac.uk or by telephone +44 (0)20 7590 4234. https://www.rca.ac.uk/more/special-collections/special-collections-books/colour-reference-library/Featured image: Digital photograph of my darkroom wall (shadows of drying line with film clips)

Fingertips in Time - John Hedley

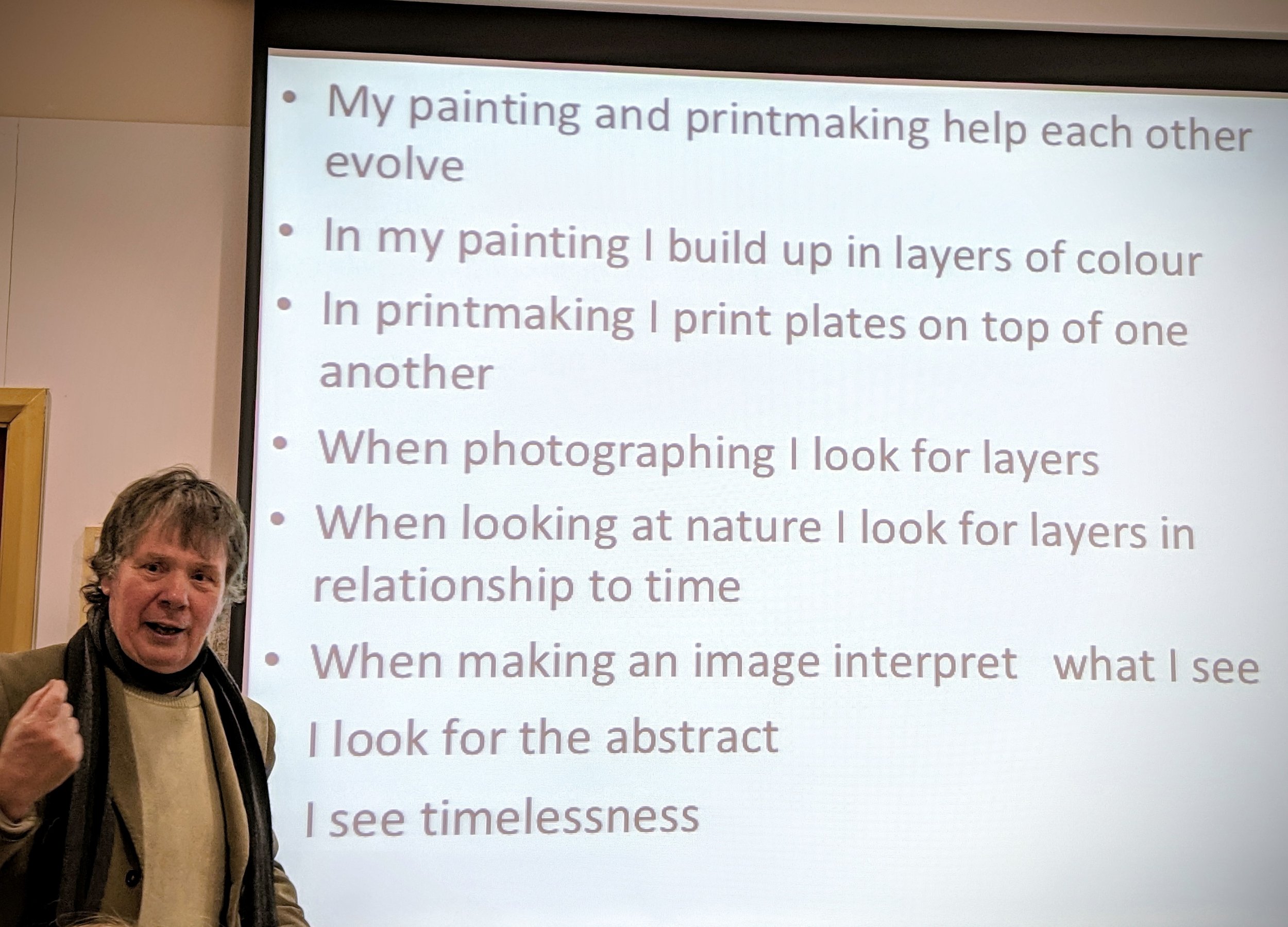

The painter and printmaker John Hedley gave a talk on the work in his exhibition 'Fingertips in Time' at Oriel Colwyn on Thursday 7th March 2019. The exhibited images fall into two series, one of trees presented as monochrome prints which looked almost like charcoal sketches and the other, a series of multicoloured print studies of volcanic rock formations from two sites, one at Llandwyn Island on Anglesey and the other in Crete. John talked about the techniques he used in making these and also more extensively about his work in general including his paintings, sculpture and work with mixed media. My interest in his processes relates to his use of digital camera photographs as the starting point and how he went about transforming these into intaglio prints. He explained that he prints the photographs as a positive image at high resolution (600 dpi bitmapped) onto acetate, using an A3 inkjet photo quality printer. The acetate is then exposed in a UV light box (Natgraph) onto a photopolymer etching plate (Solar Plate), which when processed and prepared (polished) can be inked up for printing onto dampened paper in a press. He explained that until recently, he had been wary of using photography as he felt this was almost like cheating. When he started using a digital SLR camera he discovered that the learning process was more complicated than he had anticipated; the main difficulty being obtaining a perfect tonal range which would be compatible with his printmaking processes. After a fair amount of "learning by mistakes" he has found that photography and image processing (layering in Photoshop) is now influencing his painting which has become "more abstract, in a round about way". He feels the main difference between most photographers and painters is that photographers feel they need to know what the end result will be at the time they press the shutter - i.e. classic 'pre-visualisation' as advocated by Ansel Adams (Schaefer, 1992) and the f64 group (and most photographers since then). In his printmaking, especially with multiple layers of coloured inks, he seldom knows what it will look like when finished and part of the process of abstraction is that the image evolves layer by layer, as it is being made.

He explained that until recently, he had been wary of using photography as he felt this was almost like cheating. When he started using a digital SLR camera he discovered that the learning process was more complicated than he had anticipated; the main difficulty being obtaining a perfect tonal range which would be compatible with his printmaking processes. After a fair amount of "learning by mistakes" he has found that photography and image processing (layering in Photoshop) is now influencing his painting which has become "more abstract, in a round about way". He feels the main difference between most photographers and painters is that photographers feel they need to know what the end result will be at the time they press the shutter - i.e. classic 'pre-visualisation' as advocated by Ansel Adams (Schaefer, 1992) and the f64 group (and most photographers since then). In his printmaking, especially with multiple layers of coloured inks, he seldom knows what it will look like when finished and part of the process of abstraction is that the image evolves layer by layer, as it is being made. Expanding on this, he explained that in deciding what to photograph he looks for the the most obscure and abstract things he can find, often now looking in nature for visual representations of layers; one tree in front of others, shadows on rocks or sand, layers in dead wood or rock formations, layers in time. In interpreting what he can see, he is taking from nature then playing and abstracting from it. He described this process as "being like building with Lego - start with the finished object - take it apart then re-build it - it will look similar but not exactly the same".To my surprise, I found that I had more in common with his approach than I had expected. In discussion with the audience, he talked of shadows in art as having ambiguity, transience - similar to the feelings I have been trying to capture in my photographs of shadows. I had not previously grasped the significance of layers but in many of my images, that could be what gives them the impression of texture. I felt comfortable with his explanations of abstraction, a concept I have had difficulty fully understanding previously. He is clearly happy now using a hybrid of digital photography and traditional printing, feeding contemporary technology into long established analogue processes. He is going to be in Greece for the next couple of months but has offered to let some of us visit his studio to share his technical knowledge. Having never seen photo-etching in practice or intaglio prints being made, I still have some difficulty in understanding exactly how it works and this is now on my list to do over the summer. I am sure that the learning curve for developing his printmaking skills was much steeper and longer than it took him to get what he needed from digital photography but I am still interested in printing digital negatives on acetate for use with historical U-V light based photographic processes and his advice on file preparation and printing technique could be invaluable.His final comment on his acceptance of photography as a tool for image making was to concede that "the mobile phone has become the sketch-book of the 21st century".The images used to illustrate this post were captured on my mobile phone camera.Schaefer JP (1999) 'Visualisation: The Art of Seeing a Photograph' In: Ansel Adams Guide - Basic Techniques of Photography Book (1); Revised edition, Boston-New York-London, Little, Brown and Company, pp 131-134.

Expanding on this, he explained that in deciding what to photograph he looks for the the most obscure and abstract things he can find, often now looking in nature for visual representations of layers; one tree in front of others, shadows on rocks or sand, layers in dead wood or rock formations, layers in time. In interpreting what he can see, he is taking from nature then playing and abstracting from it. He described this process as "being like building with Lego - start with the finished object - take it apart then re-build it - it will look similar but not exactly the same".To my surprise, I found that I had more in common with his approach than I had expected. In discussion with the audience, he talked of shadows in art as having ambiguity, transience - similar to the feelings I have been trying to capture in my photographs of shadows. I had not previously grasped the significance of layers but in many of my images, that could be what gives them the impression of texture. I felt comfortable with his explanations of abstraction, a concept I have had difficulty fully understanding previously. He is clearly happy now using a hybrid of digital photography and traditional printing, feeding contemporary technology into long established analogue processes. He is going to be in Greece for the next couple of months but has offered to let some of us visit his studio to share his technical knowledge. Having never seen photo-etching in practice or intaglio prints being made, I still have some difficulty in understanding exactly how it works and this is now on my list to do over the summer. I am sure that the learning curve for developing his printmaking skills was much steeper and longer than it took him to get what he needed from digital photography but I am still interested in printing digital negatives on acetate for use with historical U-V light based photographic processes and his advice on file preparation and printing technique could be invaluable.His final comment on his acceptance of photography as a tool for image making was to concede that "the mobile phone has become the sketch-book of the 21st century".The images used to illustrate this post were captured on my mobile phone camera.Schaefer JP (1999) 'Visualisation: The Art of Seeing a Photograph' In: Ansel Adams Guide - Basic Techniques of Photography Book (1); Revised edition, Boston-New York-London, Little, Brown and Company, pp 131-134.

Colour in the landscape

The recent darkroom experiments with colour photograms have unexpectedly raised my level of awareness of colour when I am out walking with my camera. One of the drawbacks of digital imaging technology is the tendency to produce images with luridly over-saturated colours, either through over-enthusiastic processing by the users or their over-reliance on the software algorithms built in to modern cameras and mobile phones. The prevalence of this particularly in social media platforms has resulted in an expectation that landscapes will be vividly coloured, almost like a re-setting of the expected norm. We all however perceive colours differently and inconsistently - "in visual perception a colour is almost never seen as it really is - as it physically is" - and - "it is necessary to recognise that colour deceives continually", (Albers 1963). The rock formations photographed for this article are near the Western end of Porth Ceiriad on the Lleyn Peninsula. The colours in life are subtle and muted and I have 'enhanced' them to a point where they are no longer true representations of what I saw but the photographs are now a better representation of their perceived effect when I was there. I doubt if I would previously have treated them in this way but the result feels acceptable, perhaps because the interaction of the almost complementary orange browns and bluish greys remains harmonious. Nobody unless they were there at that time could know the difference but have I sacrificed photographic integrity for a more pleasing aesthetic effect?Albers J (1963). 'Interaction of Color'. New Haven, Yale University Press. p1 (My edition of this is the Fiftieth Anniversary (4th) Edition of the paperback version, still in print and published in 2013).

The rock formations photographed for this article are near the Western end of Porth Ceiriad on the Lleyn Peninsula. The colours in life are subtle and muted and I have 'enhanced' them to a point where they are no longer true representations of what I saw but the photographs are now a better representation of their perceived effect when I was there. I doubt if I would previously have treated them in this way but the result feels acceptable, perhaps because the interaction of the almost complementary orange browns and bluish greys remains harmonious. Nobody unless they were there at that time could know the difference but have I sacrificed photographic integrity for a more pleasing aesthetic effect?Albers J (1963). 'Interaction of Color'. New Haven, Yale University Press. p1 (My edition of this is the Fiftieth Anniversary (4th) Edition of the paperback version, still in print and published in 2013).

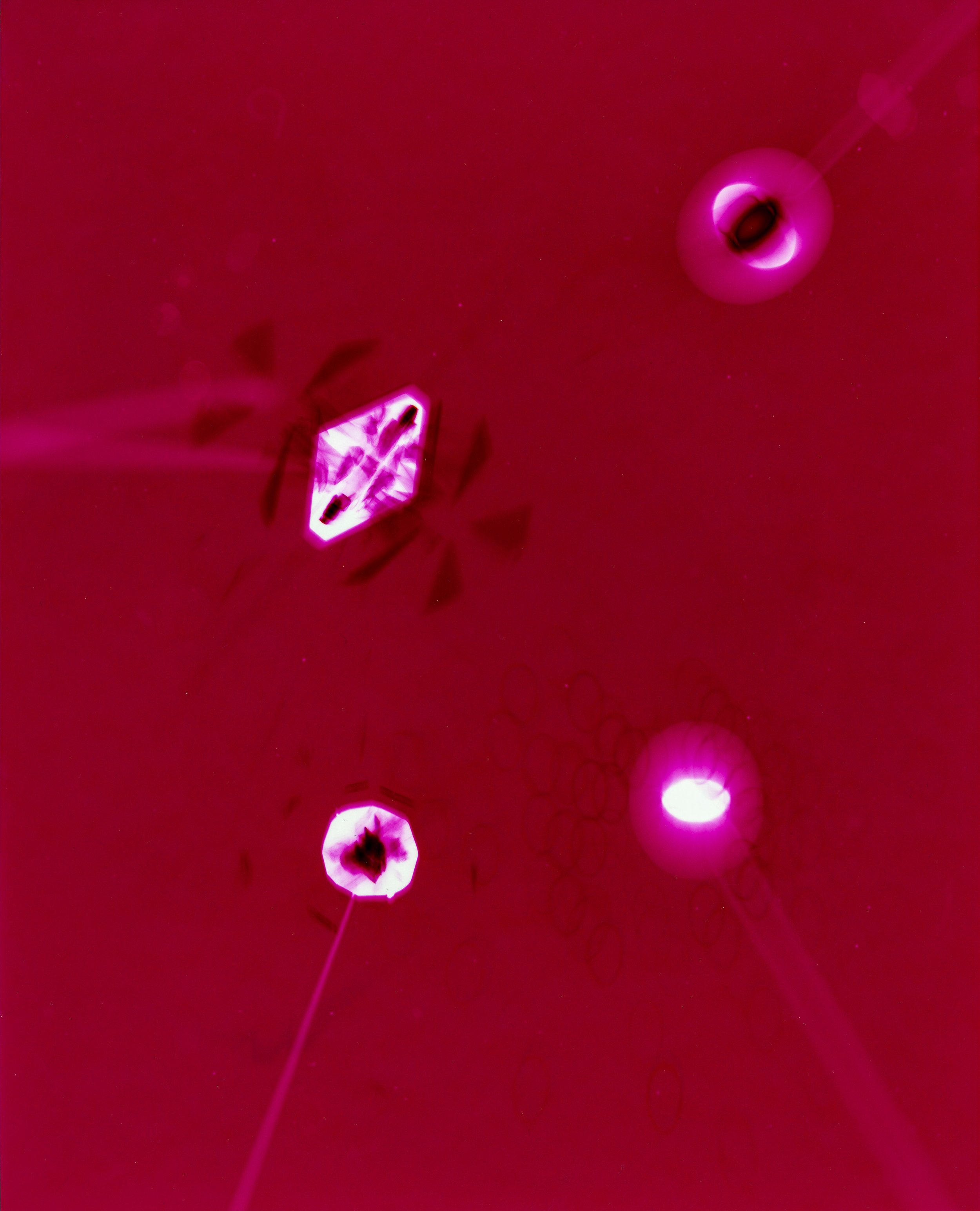

Progress with colour photograms

Having achieved at least a degree of control over colour filtration settings I have started to explore the potential of the process for making photograms in colour. To reproduce textural details in the images, the materials used need to be at least semi-transparent and the designs in waste plastic and glass food and drink containers from my recycle bin are looking like promising subjects. This has evolved from some earlier monochrome work and I have also photographed the textures in other more dense packaging using digital cameras. As a further strand of the exploration of this issue I have also started photographing rubbish and household goods washed up on beaches or illegally disposed in the countryside, problems which particularly affect coastal, island and rural communities, where access to recycling facilities is relatively limited. In these images, I have also tried to consider the design elements manufacturers incorporate to improve the effectiveness of the protection the packaging provides as well as making them more aesthetically attractive to potential customers. Although the images have been scanned for inclusion in this post, the original images were all produced using RA4 chemistry with colour photographic papers, sometimes using multiple exposures . The colours in some have been produced entirely by manipulation of the enlarger filters as in the image above but in others, the inherent colour of the materials has also been utilised - the image below was made using a turquoise blue container lid (the process resulting the in reverse complementary colour in the image)

In these images, I have also tried to consider the design elements manufacturers incorporate to improve the effectiveness of the protection the packaging provides as well as making them more aesthetically attractive to potential customers. Although the images have been scanned for inclusion in this post, the original images were all produced using RA4 chemistry with colour photographic papers, sometimes using multiple exposures . The colours in some have been produced entirely by manipulation of the enlarger filters as in the image above but in others, the inherent colour of the materials has also been utilised - the image below was made using a turquoise blue container lid (the process resulting the in reverse complementary colour in the image) The analogue process used to produce the images could also be considered as a form of 'recycled' technology. Although still in use, the range of colour papers and chemistry is now very limited and most of those available are packaged in quantities for commercial automated machine processors rather than small scale or home use. The range and depth of colour which can be obtained is very encouraging - further experimentation is called for.

The analogue process used to produce the images could also be considered as a form of 'recycled' technology. Although still in use, the range of colour papers and chemistry is now very limited and most of those available are packaged in quantities for commercial automated machine processors rather than small scale or home use. The range and depth of colour which can be obtained is very encouraging - further experimentation is called for.

Colour darkroom printing

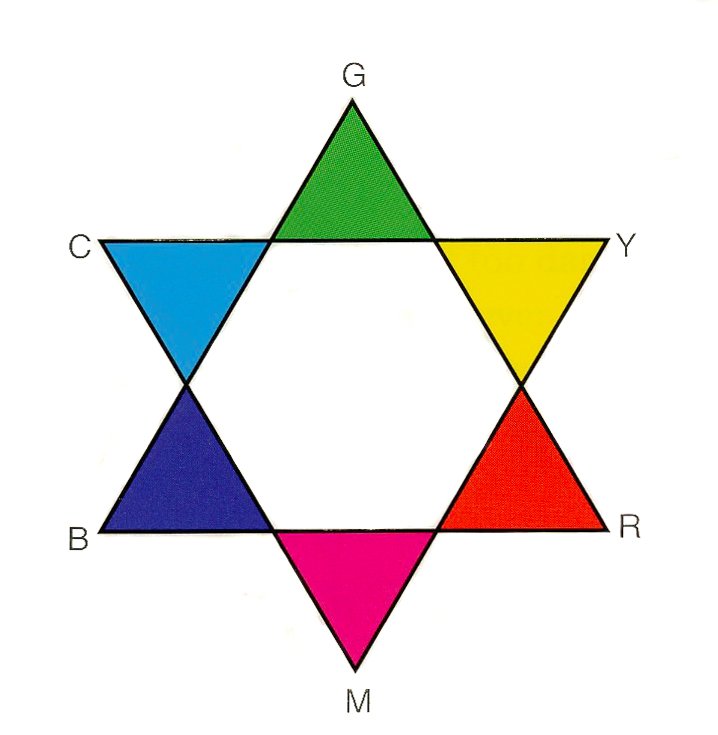

In looking for more imaginative ways of making photograms in the darkroom, I have been exploring the possibility of creating them in colour using 'C' Type papers and RA4 chemistry. As a result of the panchromatic nature of colour materials, the practicalities of colour printing are more complex than monochrome printing with silver gelatin processes. The papers need to be handled in total darkness (no safelight). They degrade quickly if not stored correctly and the chemistry also needs to be fresh. The processes require higher temperatures for the chemicals which need to be tightly controlled, especially the colour developer (to plus or minus 0.5 degrees). Although black and white darkroom papers can produce interesting results even when many years out of date, after several completely unsuccessful attempts to produce an image, I have learned the hard way that this does not work with expired colour chemicals or with colour papers which had been stored for several years. Having obtained a new box of Fujicolor Crystal Archive paper and Tetenal RA4 chemistry, I have finally managed to make some test prints which have strong bold colours and am hopefully about ready to start making some new images. Getting to this stage proved more challenging than initially expected and I found it difficult to think in terms of inverted colours as well as inverted tones. For example, correction for a yellow cast in a print, requires the addition of its' complementary colour i.e. blue (Fig 1. above). The colour produced on the print is however the inverse of colour of the light projected on it so confusingly, to correct a yellow cast it is necessary increase by filtration, the amount of yellow emitted by the light source (see Fig. 2 below). When researching this I realised with regret that I had thrown out all my basic "how to" photography books which at the time seemed redundant but would have contained all this information. I also discovered that in most of the current versions of these books available in the college library, the sections on colour printing in the darkroom have been largely replaced with information on digital imaging but I found a limited amount of what I needed in "Langford's Advanced Photography" (8th Edition).

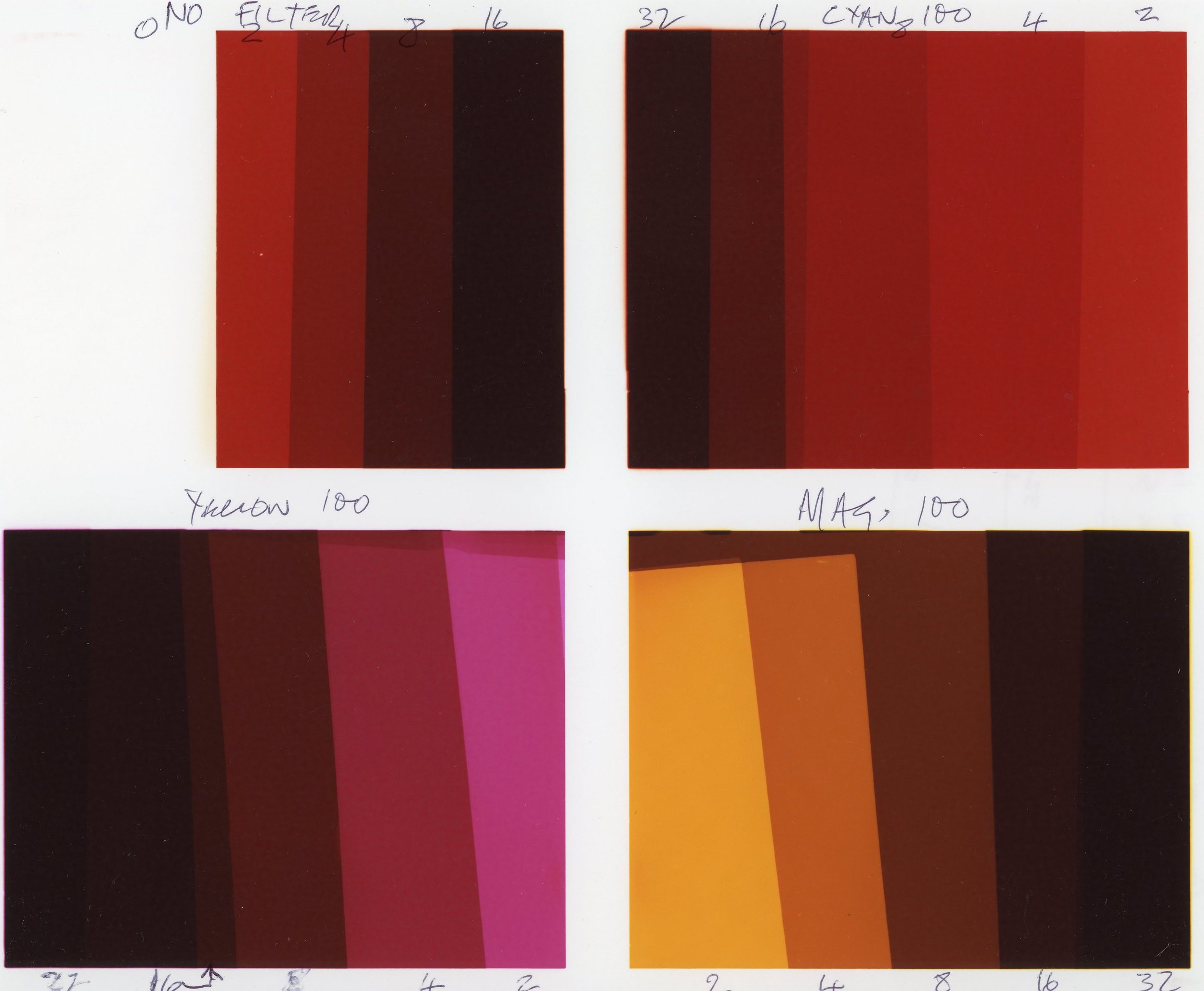

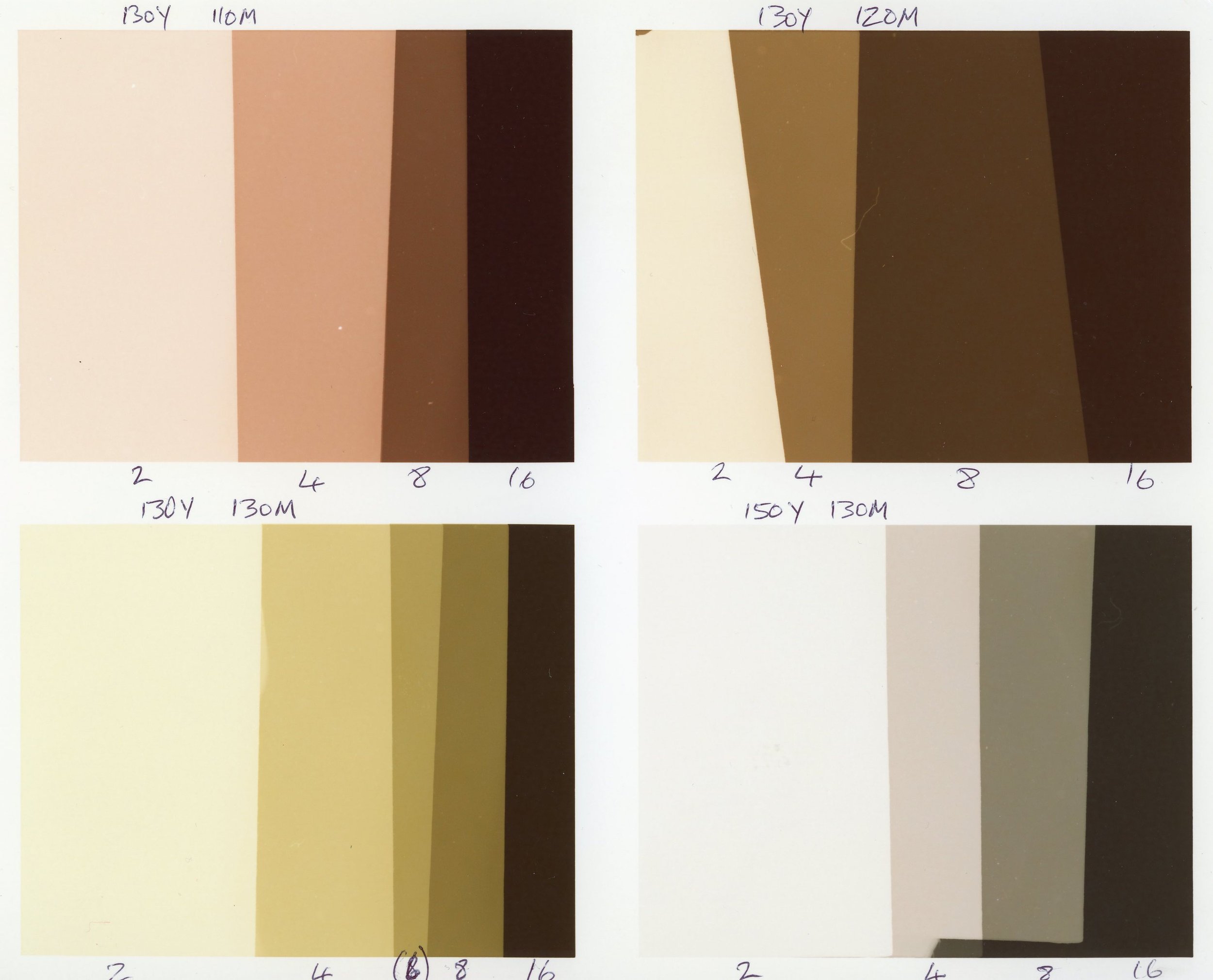

Getting to this stage proved more challenging than initially expected and I found it difficult to think in terms of inverted colours as well as inverted tones. For example, correction for a yellow cast in a print, requires the addition of its' complementary colour i.e. blue (Fig 1. above). The colour produced on the print is however the inverse of colour of the light projected on it so confusingly, to correct a yellow cast it is necessary increase by filtration, the amount of yellow emitted by the light source (see Fig. 2 below). When researching this I realised with regret that I had thrown out all my basic "how to" photography books which at the time seemed redundant but would have contained all this information. I also discovered that in most of the current versions of these books available in the college library, the sections on colour printing in the darkroom have been largely replaced with information on digital imaging but I found a limited amount of what I needed in "Langford's Advanced Photography" (8th Edition). Out of the box, colour papers have a cyan coloured coating on the surface which acts as an anti-halation layer and presumably at least partially corrects for the orange mask present on the surface of most colour negative films. My plan is to attempt to make colour photograms and am not using negatives so the cyan coating produced a very strong reddish brown cast on my initial tests (Test print 1) and after experimentation I found that much stronger yellow and magenta filtration than anticipated was needed to achieve anything close to neutral greys (bottom (R) image on Test print 7).

Out of the box, colour papers have a cyan coloured coating on the surface which acts as an anti-halation layer and presumably at least partially corrects for the orange mask present on the surface of most colour negative films. My plan is to attempt to make colour photograms and am not using negatives so the cyan coating produced a very strong reddish brown cast on my initial tests (Test print 1) and after experimentation I found that much stronger yellow and magenta filtration than anticipated was needed to achieve anything close to neutral greys (bottom (R) image on Test print 7).

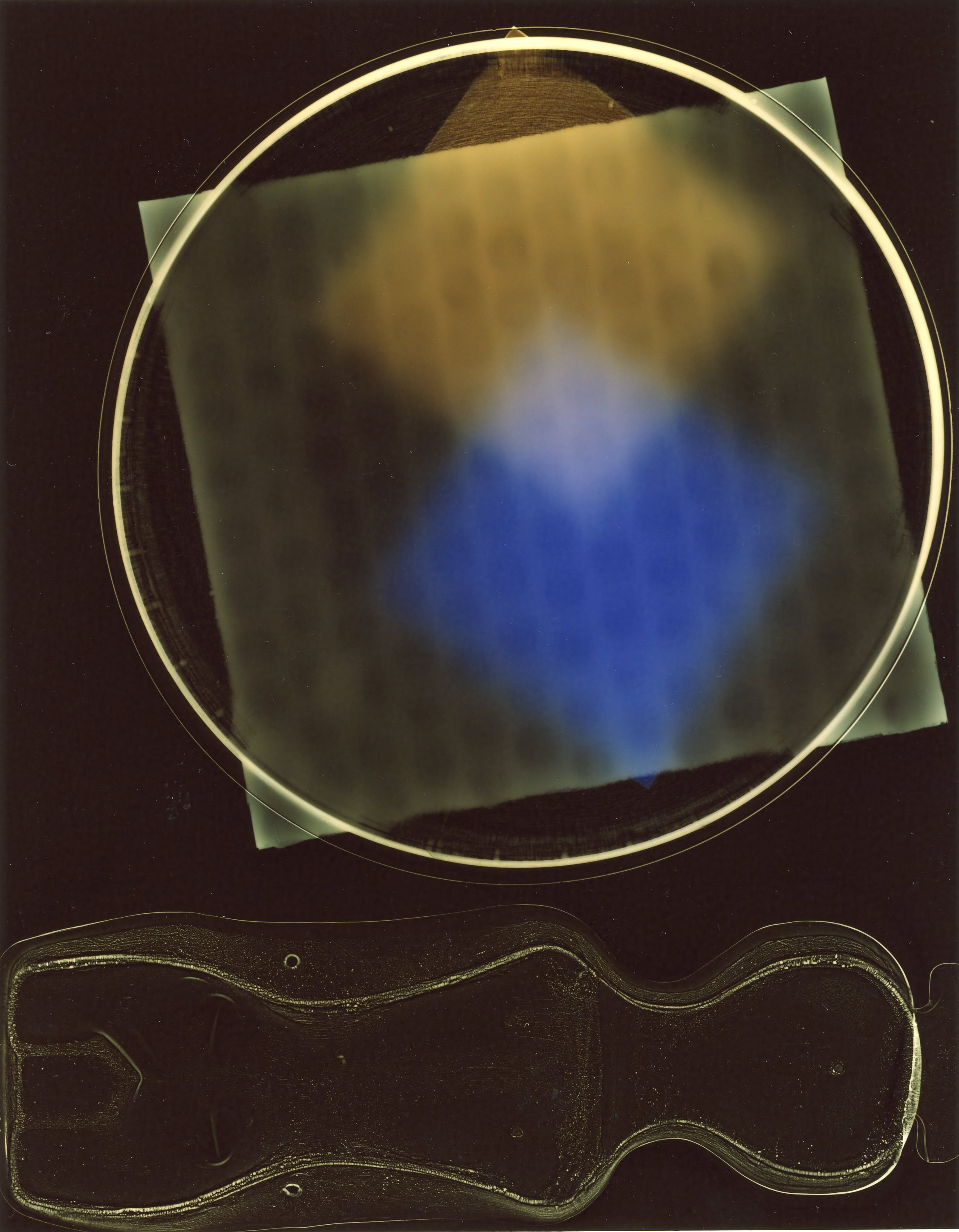

In the process of reaching a reasonable approximation for the basic colour filtration required for neutral tones, I have discovered that it will be possible to produce a wide range of both bold and subtle colours which potentially offer exciting possibilities for the work I am hoping to create. This is will undoubtedly involve more experimentation and although the element of serendipity is often useful in producing photograms, in addition to fine tuning the colours utilised, I will need to develop a technique for getting the objects used into the optimum position on the paper in complete darkness before making the exposure. The image below, my first crude attempt to produce a colour photogram, shows some of the visual potential of the technique, while demonstrating the need to tackle the issue of alignment of the objects on the paper.

In the process of reaching a reasonable approximation for the basic colour filtration required for neutral tones, I have discovered that it will be possible to produce a wide range of both bold and subtle colours which potentially offer exciting possibilities for the work I am hoping to create. This is will undoubtedly involve more experimentation and although the element of serendipity is often useful in producing photograms, in addition to fine tuning the colours utilised, I will need to develop a technique for getting the objects used into the optimum position on the paper in complete darkness before making the exposure. The image below, my first crude attempt to produce a colour photogram, shows some of the visual potential of the technique, while demonstrating the need to tackle the issue of alignment of the objects on the paper. Reference: Langford M and Bilissi E, 'Negative/Positive Colour Printing' In: Langford's Advanced Photography (8th Edition) pp 296-301. Focal Press (an imprint of Elsevier), London, 2011.

Reference: Langford M and Bilissi E, 'Negative/Positive Colour Printing' In: Langford's Advanced Photography (8th Edition) pp 296-301. Focal Press (an imprint of Elsevier), London, 2011.